I’m pretty sure that my four years at Stanford have been the greatest four years in the history of Stanford football. Three Rose Bowls. Three conference championships. And the most satisfying game I’ve ever witnessed as a Stanford football fan: a game where the Cardinal drove No. 6-ranked, 12-1 Iowa into the dirt and kept their foot on the gas until the Hawkeyes were a thing of the past. What a time to be alive.

But it’s incredible how difficult that seemed at the time. Stanford’s record slipped in 2014, even though the team would have won 10 games with better injury luck. And few people expected Northwestern to be a good team, so when they beat Stanford in Evanston to open the 2015 season… well, you can put two and two together yourself. I was worried. I’ll be the first one to admit it.

Still, Stanford changed its game plan against Central Florida a week later, and the offense roared to life. It helped that Kevin Hogan made the leap that had been brewing since the second half of 2014. He began taking over games with pocket presence and smart checks at the line — something we would have more clearly seen if Christian McCaffrey’s dominance hadn’t made throwing the ball almost unnecessary. Scheme, however, played a major role. Stanford has historically been a team built to run the Power run play. But Power ground to a halt after teams started selling out to stop it, and I’d argue that nothing typified Stanford 2.0 more than a new reliance on the outside zone, a very different kind of running play. Christian McCaffrey ripped off his longest run of the night on an expertly blocked outside zone play that highlighted both the offensive line’s mastery and McCaffrey’s God-given genius.

At this point, the game’s already over. Stanford’s up by 35, and the second half has barely started. But Christian McCaffrey pulls off a big run because, well, why not. (Online readers can watch the video of the play here, but note that the ESPN feed cuts off the first bit of the play.)

The outside zone looks like a simple play: The offensive line takes a step to the side and blocks in unison. Linemen make double-teams to move defensive linemen out of the way and work together to free up blockers to hit the linebackers. The play is difficult to key against because the point of attack isn’t always predetermined: There’s a target, but cutbacks are easier to find on outside zone than they are on most running plays. Patient running backs will wait and see how the blocking unfolds: they trust that if the offensive line can win its battles, some kind of hole will open up. Of course, this play is almost infinitely more difficult than I made it seem. In real life, it’s notorious for taking up half a team’s practice time, if not more. That’s why most teams don’t fully commit to it.

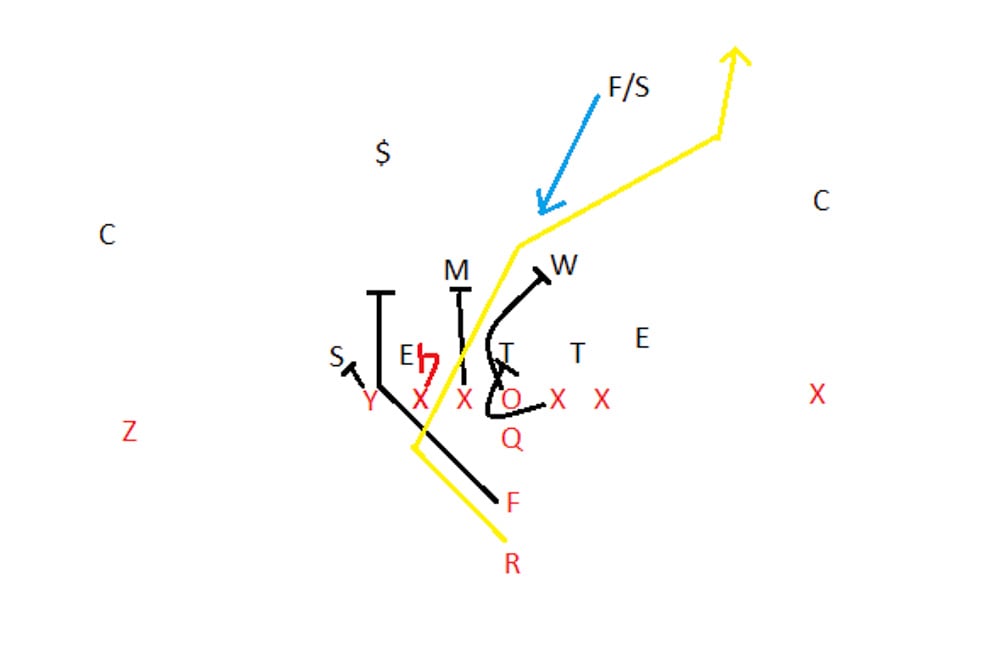

Outside zone is a great play against defensive lines that like to get low and plow right through north-south runners. It shifts the initiative back to the offensive line by moving the line laterally, forcing the defensive line to get upright and sacrifice their leverage in order to follow the blockers. And because McCaffrey is such a lethal cutter, Stanford wants to get the front seven moving and making mistakes, putting McCaffrey (R) in position to do what he does best.

McCaffrey’s gotten a lot better at reading his blocks and running between the tackles over the course of the season, and he’s a joy to watch on zone. But Stanford’s also willing to help him out by using fullback Chris Harrell (F) to lead block (“insert,” in football jargon) for him on zone, which you don’t normally see. It’s an advanced technique, really, and you don’t normally see Stanford do this, but having an extra blocker can be very helpful; Harrell leading the line against the linebackers means that the offensive line can focus on opening holes at the line of scrimmage. Throwing a fullback strongside entices defenses to sell out and open up the backside cutback. And if the safeties have tackling responsibilities, as they do here, the fullback can also draw in the near safety, forcing a more difficult tackle from the far safety. This gives McCaffrey more time to work.

The blocking on this play is excellent, even though Iowa is playing with five men on the line and Stanford’s been running the ball all game. Tight end Dalton Schultz (Y) pushes around his opposite number, strongside linebacker Bo Bower (S), to open up a hole off tackle. Harrell leads through the hole. Left guard Joshua Garnett takes the middle linebacker (M), who is shooting his gap. Center Graham Shuler and right guard Johnny Caspers plan to double-team the strongside defensive tackle just long enough to put him under control, after which Shuler releases downfield to hit the weakside linebacker. Right tackle Casey Tucker tries to throw a cut block (a popular option on backside outside zone runs) on the weakside tackle, but after the tackle stunts wide of the play, the question is academic.

The key block on this play, however, is that of left tackle Kyle Murphy. Murphy has a difficult block to begin with: He has to reach a defensive end that’s shaded to his outside and push him inside, widening the hole. But Murphy makes a great heads-up play here (red arrow). He sees Iowa’s strong safety Miles Taylor ($) crash the hole, keying in on Harrell. He knows that Garnett will have the middle linebacker under control and that free safety Jordan Lomax (F/S) is too far away to make a play. Instead of hooking his man inside, Murphy feels the end working outside to the point of attack and uses his inside leverage to throw him even further outside, squeezing the original hole but also opening a massive cutback lane to his right. In this way, Murphy’s intelligent snap decision forces McCaffrey to cut upfield between the tackles — where Murphy knows there will be space.

After that, McCaffrey does his work. Taylor is blocked by Harrell, and Lomax takes a bad route to the ball. McCaffrey jukes the weakside corner and runs to daylight. While Iowa missed a ton of tackles on New Year’s Day, and Iowa fans were very angry as a result, everybody misses tackles against McCaffrey. He has strange powers. He goes for 30 yards. He did stuff like that all day.

***

Relying on outside zone to power the Stanford run game was a legitimately momentous decision. When Stanford is getting stoned on Power, it typically changes to different plays, to be sure, but in the past it’s only stuck with the ancillary plays as long as it took for defenses to stop keying in on Power. This year seemed to follow the same script at first: the Cardinal still showed that it could run directly up the middle instead of off tackle, and it was a lot more willing to run the zone read and the pin-and-pull outside zone (looks like a sweep) than it had been in years past. The plays themselves weren’t new to the Stanford offense. But this year they earned the team’s trust.

Outside zone is a great example of this. In addition to the pin-and-pull, Stanford’s run the traditional form of outside zone (“stretch,” the play documented in this column) to great effect in some years. The 2013 line was exceptionally adept at stretch. But Stanford never committed to stretch to the extent that it did this year. In past years, Stanford ran Power in order to grind down the defense and gain the upper hand. Now it primarily runs Power against teams like UCLA when it already has the upper hand.

Stanford made its name by crafting a powerful identity — running the ball with Power. But Stanford has also been successful because it has adapted. David Shaw started Kevin Hogan back when Hogan’s offensive repertoire was very limited, and adjusted the offense to fit Hogan’s strengths. Derek Mason stopped a year’s worth of relentless jet sweeps with adjustments of his own, rolling his defensive backs to snuff out sweeps before they occurred. And when Stanford ground to a halt against Northwestern, the Cardinal fully embraced a scheme that attacked the outside and forced safeties and cornerbacks to tackle. Stanford’s often mocked by outsiders for its stubborn commitment to its offensive identity. But in the years to come, I am confident Stanford will endure because it’s shown an ability to change.

***

As usual, I do feel somewhat bad about covering the plays I cover, because (as usual) I’m not reviewing a TD play after a game full of touchdowns. (In fact, the McCaffrey run “only” set up Stanford’s lone field goal of the day.) So let’s take a look at the touchdowns.

- Running back option route to Christian McCaffrey. Stanford combines a frontside zone beater with a backside option route, knowing that against man coverage, Stanford will get McCaffrey 1-on-1 out of the backfield. The option route call is basically a “step 1: snap the ball, step 2: ???, step 3: profit” idea, but Christian McCaffrey is the living embodiment of “???”, so it works anyway. One pair of broken ankles later and McCaffrey’s on his way to the end zone. Chris Brown, of Smart Football and (the late) Grantland, is the best Xs and Os writer in the business — and he’s also great at giving encouragement to know-nothing freshmen. We’re lucky that he broke this play down for us.

- Zone read QB keeper. Plenty of guys can talk about the zone read. Oregon runs it better than anybody, so let’s go with Charles Fischer at FishDuck for a simple tutorial.

- Pick-six by Quenton Meeks. Rose Bowl color commentator Jesse Palmer hit the nail on the head: You can’t telegraph the ball on a short out route. As soon as he saw man coverage against a man-beater route combination, Iowa QB C.J. Beathard stared down his target all the way.

- McCaffrey houses a punt return. Still no idea how that happened. You can’t break that down. You just marvel at the greatness of Christian McCaffrey.

- Trick play – fake fumble, then bomb to Michael Rector. Really interesting that Stanford would risk putting the ball on the ground with a defenseless QB, but it was a heavy protection package and Stanford was already up by 28 anyway. Why not throw the dagger?

- Beautiful stop and go to Michael Rector. I don’t think Shaw wanted to stick it to Iowa in the closing minutes — I just think he wanted Hogan to not end his career with an interception. David Shaw is rarely sentimental, but Hogan deserved it.

You know the game is good when I’m using bullet points to cover touchdowns. Say it once more, with feeling: What a time to be alive.

***

Finally, I want to say something about myself. I’ve spent four years on the Stanford football beat. This actually makes me the longest-tenured football writer at the Daily, as freshmen typically start out on other beats. The only reason I got to get on the beat in my first year was because I was interested in trying something that only one other guy at The Daily could do – talk about Xs and Os – and Sam Fisher didn’t have the time to do that.

Instant Replay will never be remembered as my major work at The Stanford Daily. It gets far fewer clicks than my opinions column and my regular sports column; it doesn’t have the reach of the Editorial Board; it certainly doesn’t carry the responsibility that being a managing editor brings. Yet I am quite sentimental about this series, because without Instant Replay, none of this happens – not the columns, the Editorial Board, not the head job at the Opinions Section. Instant Replay is a niche within a niche. And yet it’s the reason why I started on The Stanford Daily all these years ago.

I signed up for The Daily in my freshman year to cover news; in fact, if you go online and see my writer archive, you’ll see my first piece. It was titled “Big Game”…wait…”Big Game Scheduling Causes Problems for Gaieties Cast.” I left the news section two weeks into my freshman year. I stayed with the Daily because Miles Bennett-Smith, the sports editor in these days, gave me the opportunity to follow up on this silly football tactics idea I came up with on my first day here. Without a defined role, I might well have left otherwise. Plenty of freshmen sign up at The Daily because they worked at their high school newspaper and leave after a quarter because they realize news writing isn’t for them. I could easily have decided I was going to join the debating team or Stanford in Government. I seriously considered it, actually.

So thanks to Miles and football editor Sam Fisher for having the vision to bring in a kid who didn’t know what to say unless it was about football. And to my readers, thank you. I like to tell people who email me that readers are why my job exists. In this case, that’s not actually true: my job existed before I had any readers. This was my first gig. But readers are why being at The Daily has been so fun.

Contact Winston Shi at wshi94 ‘at’ stanford.edu.