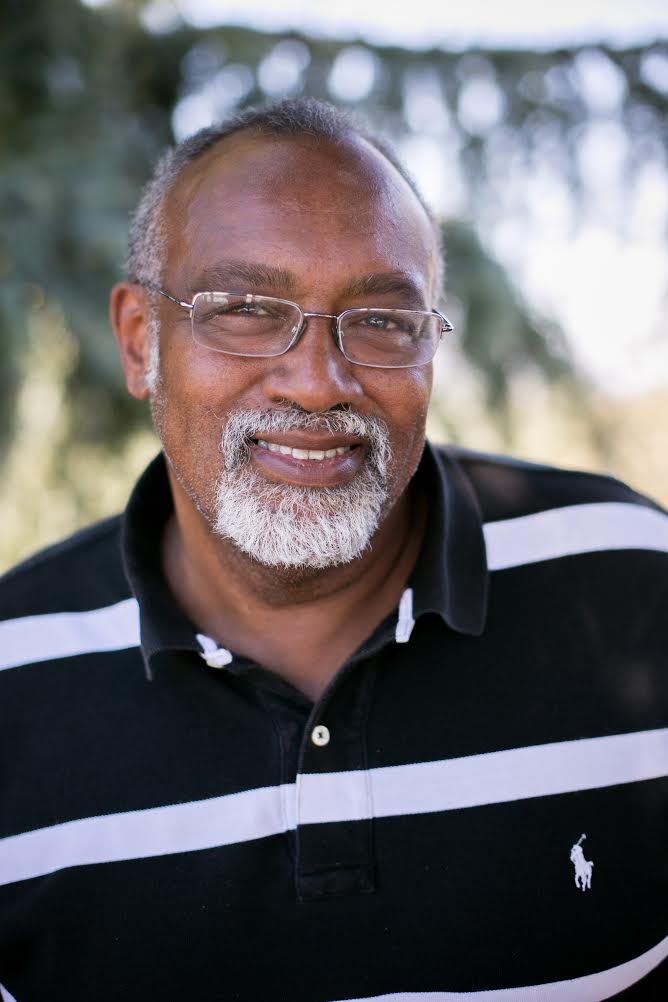

Glenn Loury, Merton Stoltz Professor of the Social Sciences and professor of economics at Brown University, is at Stanford’s Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences (CASBS) as a 2015-16 fellow. As part of the CASBS symposium series, he gave a talk last night titled “Racial Inequality in 21st Century America: Where Do We Go from Here?” The Daily sat down with Loury to discuss his perspectives on racial inequality in the United States, the memoir he is writing and his time at Stanford.

The Stanford Daily (TSD): Why did you choose racial inequality as the subject of your talk for the upcoming CASBS symposium?

Glenn Loury (GL): It’s what I’ve been working on and writing about throughout much of my academic career. So it was really very natural for me to do that. I’m also writing an autobiography, and so I’m reflecting a lot on these race and inequality issues in that context.

TSD: What makes incarceration “a leading case in point” of what you are trying to convey in your talk?

GL: Nine years ago, I gave the Tanner Lectures on Human Values here at Stanford, sponsored by the Ethics in Society Program, and I chose incarceration and race as my subject. I did the research, I put out a small book based on those lectures the following year. I have since had the occasion to serve on a number of study groups and scholarly panels. One was called together by the National Academy of Sciences to issue a report on the causes and consequences of high rates of incarceration in the United States.

Since I had that experience, and I have that knowledge, it seemed very natural to me to take incarceration as the specific area to look at in terms of racial inequality. While it’s not the only thing I will talk about, it’s the one I will talk about in the greatest detail.

TSD: What do you find to be the most common misconceptions about race today?

GL: Here’s what I want to say for my own account. The most common misconception is to overstate the importance of [the] invidious motive of morally troubling or racist intention in trying to account for racial inequality. For example, in the area of incarceration a book that has become very famous and influential is called “The New Jim Crow” by Michelle Alexander. The book has merit and I admire it. But think about how this is being framed. Mass incarceration is the new Jim Crow, meaning we should understand mass incarceration in the same spirit as we understand slavery or segregation in the south of the United States in the early 20th century.

It’s true that the war on drugs has a lot problems and some of them are racial. It’s true that a lot of police departments are manned by individuals who are maybe not valuing black lives as much as one would hope they would do. But you can’t get a system of over one million African-American men in prison at any given point in time, which is what’s here in the United States today, without there having been some behavior on [their] part that ended up getting them in trouble with the law — whether we talk about drug-selling gangs or violence or other types of activities.

It’s just too simple now in the 21st century to use that same framework that we are familiar with from the past to explain it. Part of what we have to take on board, I would argue, is that there have been consequences of past discrimination in terms of blighting the lives and affecting the behavior of current people. Having a straight-line interpretation of the inequality by race as coming about from discrimination or by bad behavior by white people or supremacists, I want to say that’s too simplistic.

Part of what we’re seeing is based on the behavior of black people who are at the bottom themselves. I’m not blaming them. I’m just describing what’s going on. That behavior can be explained.

Case in point: Lacquan McDonald was shot dead by the Chicago police a year and some months ago. What the cop did is terrible; on the other hand, what is this kid doing at 1 o’clock in the morning in the street with a knife in his hand? He has been failed, Lacquan McDonald, at many junctures, I would argue.

We can blame the state, we can blame capitalism, there’s enough blame to go around – the schools that didn’t work, the fact that there are no jobs there. But white supremacy doesn’t give me a whole lot of insight to how this kid met his end.

TSD: What are you hoping the audience takes away from your talk?

GL: I hope they think I’m a smart guy at the end of the day…nah, a nice guy. I’d like them not to think that I am an Uncle Tom sellout because I am against the spirit of the times a little bit. I hope that I can be understood a bit better. I don’t like the term “politically correct” anymore but it does describe something real within the liberal community: that there is only one right way to think about certain kinds of problems.

Certain figures from the right of American politics like Mr. Trump have made it so I don’t want to use it anymore. But I am politically incorrect on some of these issues. I would hope the audience comes away with a little understanding and respect for my somewhat unpopular views on these matters.

TSD: What drew you to a CASBS fellowship at Stanford?

GL: Margaret Levi, the director of CASBS, is what drew me here personally. I met her on more than one occasion and I told her I had a sabbatical leave coming up and she encouraged me to apply. I told her that my project is a memoir — I wasn’t sure that I could justify my presence among serious scholars when I am doing an autobiographical, not a scientific, research project. But she was very encouraging.

Since I did have that leave coming, and you know how much snow there is right now in the East Coast, I was happy to spend this time out here in the sunshine, and this is a pretty good life. I come into my office every day at 9 o’clock in the morning, I work until 6 o’clock at night, I break for lunch. I don’t have any meetings, I don’t have any students — all I have is my books and my notebook so I can get my work done. I’m grateful for it.

TSD: What motivated you to write a memoir?

GL: My working title for the book is “Changing My Mind.” I used to be a Reagan Republican. Now I have voted for Barack Obama twice. I used to be a crack cocaine addict. I had a very serious drug problem in my late 30s when I was a professor at Harvard University.

I was a born-again Christian, which I came into during the period I was trying to recover from drug addiction. And it was very comforting and helpful but then I fell away from the church. I am no longer a believer but I have great respect for the tradition. I now consider myself a centrist Democrat. And I don’t use drugs anymore. But I had to struggle. The problem of control, of self-knowledge, of self-discipline, of self-delusion — these kinds of reflexive thoughts are a part of my story.

I’ve lived long enough and I’ve had a series of experiences and transformations that I thought it would be helpful to me to try to sort it out and then it might make for something that is of interest for other people. I’ve been at the same time an academic writing about race and inequality but also an African-American living my life in a racialized society. I have a journey. I think I have something to say.

TSD: What is next for you after you complete your year at Stanford?

GL: I’m going back home to Providence, Rhode Island. I hope to have a manuscript maybe by the end of the summer. I feel I can get there; I’m feeling pretty good about it. And I also go back to teaching my students at Brown University.

Contact Andrea Villa at acvilla ‘at’ stanford.edu.