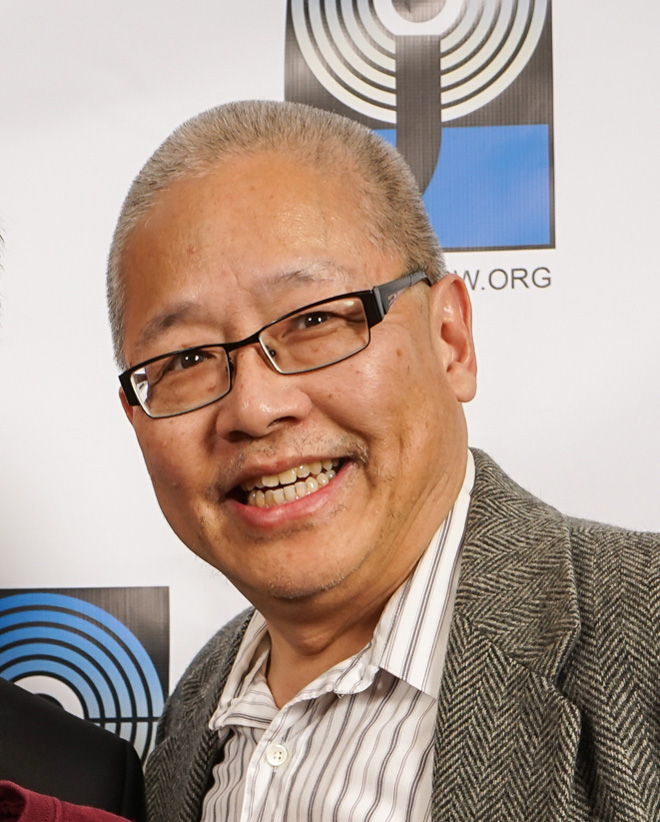

Last Thursday, the Stanford Asian-American Theater Project put on an event with Roger Tang ’79, a producer and playwright who has been called the “Godfather of Asian-American theater.” On Saturday, Tang was honored at Getting Played: Second Annual Symposium in Equity in the Entertainment Industry and Awards, moderated by PWR Instructor Kathleen Tarr. Tang graduated from Stanford with dual degrees in communications and geology. He is a member of the national board for the Consortium of Asian-American Theaters and Artists (CAATA), the Literary Manager for SIS Productions and the Executive Director of Pork Filled Productions. He also edits the Asian-American Theatre Revue. The Daily sat down with Tang to discuss his career and the Asian-American experience in the entertainment industry.

The Stanford Daily (TSD): Could you talk about how you got involved in theater?

Roger Tang (RT): Well that’s interesting because basically I don’t have a lot of formal theater training. I first got involved in theater [because] there was a tradition of dorm musicals at Stanford at the time. People would take scripts from musicals they liked. They pulled them together, they pulled together a band, they pulled together a choreographer — all within the dorm — and they put on performances … In fact, that’s how I first got started.

I produced a musical, “Promises, Promises” – Burt Bacharach, Neil Simon musical – for my first one. I was living in the Asian-American theme dorm, and in my final year I was on staff as an ethnic theme associate. What happened was that we were doing programming for the house and one of my fellow theme associates, a guy named Dave, said, “You know, I have a script. Maybe we could just pull it together and use it for the dorm as part of our programming.” That script happened to be named “FOB,” and the guy named Dave is David Henry Hwang … And [the programming] was very well received at the dorm. And he then submitted it to the O’Neill Conference, where it was selected as one of top new plays of the year. And from there it went on to the Public Theater, where it received an Obie for best new play off Broadway. And that first started me on the path in theater because, well, if David could do that, maybe I could get somewhat close to that.

And I worked with David for a couple years after that here at Stanford. David founded the Stanford Asian-American Theater Project, which I helped him do. I didn’t think of myself as a theater artist until much later, because, again, I’m not theater-trained. I thought of myself as a Asian-American activist, and art was one of the ways you can make yourself become an activist and state our story to the wider community. After that I went to graduate school, to the University of Washington, where I did communications theory, and I did my work, did my thesis, and … I was bored. So I produced more shows, and by the time I got out of there I produced four shows, which were all Northwestern premieres, and by that time I said, “Gee, you know, I got my degree, and I don’t want to be in academia.” So I went out to the real world, picked up work at the university as a fundraiser. I also joined the board of the Northwest Asian-American Theater, which was the local Asian-American theater, and one of only five at that time in the country. And then from there I became more of an administrator, raised funds for the local theater, helped build a theater. That theater still exists, and now I head up a small theater up in Seattle called Pork Filled Productions. We started out as a sketch comedy group, then we moved on over into full lights work, both original and from authors across the country. I guess my real claim to fame is that I created an email mailing list devoted to [and] for Asian-American actors and writers, back in the early 90s, and after that I also formed a website for Asian-American theater. Both of those are still existing, and I guess what the really cool thing about that is that it helped connect people from across the country. In some cases, it was sort of a lifeline for them in saying, “Okay, you know, I’m not crazy. My concerns are actually real. Other people share them.”

TSD: Could you talk a little bit more about your experience with Asian-American activism at Stanford and maybe after, too?

RT: [In the] mid-70s, [I] wasn’t at the very forefront of activism or any of the creative part, but I was in the room. I was with the people. I connected with the same people who were. I was involved with the Asian Students Association at the time. A lot of it was trying to get Asian-American studies into the curriculum – not very successful then but more successful later. I was involved with several third-world student marches for scholarships for third-world students. And it was really big then; I was part of the protest for divestment in South African investments. There were several occupations of the Old Union administration building for that. And that was an incident that David Henry Hwang talked about in his play “Yellowface.” Now after that, now up in Seattle I’ve been involved off and on with a group like the Asian Counseling and Referral Service, [and] … the National Association of Asian-American Professionals. It was a group devoted toward representation of Asian Americans in middle management and above, both in the business world and the nonprofit world. But most of my time is involved in the entertainment industry, mostly theater. I consult with a number of local theaters in the area [on] how to reach actors of color, specifically Asian, or to pass along calls for shows to Asian-American actors.

TSD: Could you talk a little bit about why you think representation in the entertainment industry is so important?

RT: Well, one thing, it’s America. I mean, America is not 95 percent white. It’s important for, one, people of color to see themselves in media and to know that their stories are part of America, and two, it’s important for people who are not Asians to know what sort of role Asian Americans have played in American life, both in the past and in the present. I’m very fond of “Paper Angels” by Genny Lim. It’s about Chinese American immigration to America in the early 20th century. Everybody who’s seen it has told me they never, never knew about Chinese-American immigration. They just thought that people were able to walk into the country, and they never knew about the Asian Exclusion Acts or the lynchings of Chinese Americans in the Western U.S. They vaguely heard about Chinese Americans’ work on the railroads, but they never knew that they were the focus of anti-immigrant ill will. And the fact that we’re seeing it again today, it really struck home for them. To me it’s so ironic that people are saying the same things, using the exact same arguments, the exact same themes, the exact same words today that they did against the Chinese back in the 19th and 20th centuries. And that show was such a great piece of art, a great piece of entertainment and a great piece of education, not only for people in the audience but for people in the cast, who sort of knew about it but only then got exact details and the feel of how it must have felt back then.

TSD: Have you seen different ways Asian-American theater has changed since you first got involved? Has it evolved over the years?

RT: Yes, it’s certainly evolved. I think theater is now seen as more of an option. I mean, there’s this pressure on people to go into something, into a major that’ll make money, but I’ve seen more and more people actually think of the arts as an option for them for self-expression. Also, I think the nature has changed. I mean, in the early years it is very ideological and politically bent because it was an outgrowth of activism as a whole. I think I’ve seen more changes in that there’re people speaking more artistically and figuratively instead of being more literal about it. I’m also seeing more humor. People are not afraid to laugh at themselves or to laugh at the issues facing them. And I’m seeing a lot more willingness of people to take a chance and create for themselves more, either in small sketch groups or theater. They might have thought, “This is just a little sketch,” but these things tend to grow and tend to build themselves up into a full-blown theater piece. I’m also seeing a lot more solo performance artists saying, “Okay, this is what I believe in, and I’m going to seek out the ways of how to say it the best way, the most creative ways, the most colorful ways.” [Back] then, there were only a few isolated spots where you could go, and now I’m seeing dozens of groups, and I’m seeing even more individual artists, where people are saying, “Okay, I can say this. It is safe for me to say this, and people will listen to me say this, and I can be entertaining and be artistic and say this.”

Contact Sarah Wishingrad at swishing ‘at’ stanford.edu.