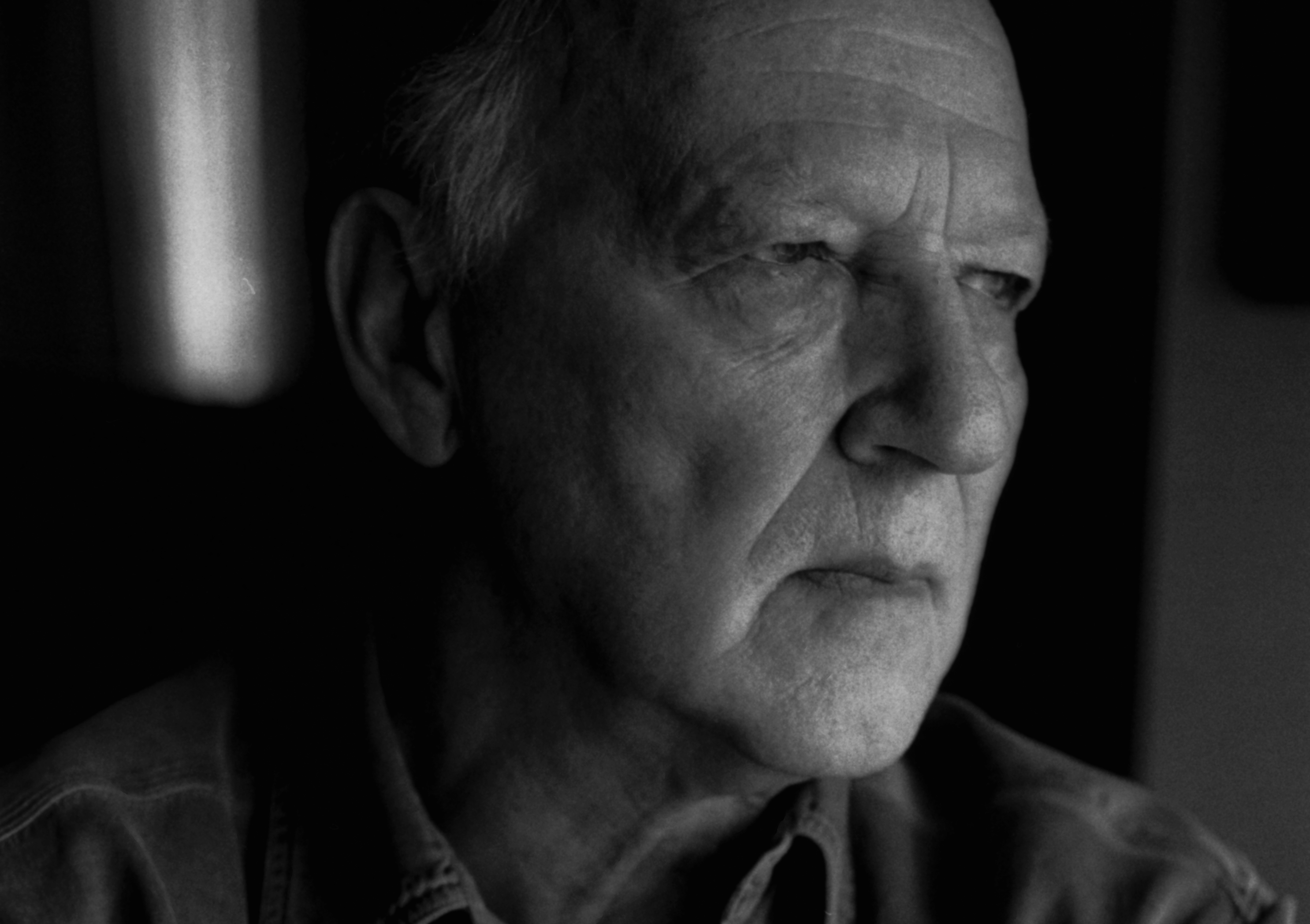

“Lo and Behold, Reveries of the Connected World” is just the latest entry in the bizarre film genre called “Herzog.” The genre’s namesake is Werner Herzog, the kooky German director who’s become meme-ified in the Age of the Internet, for his oddball profundity (analyzing Yeezy’s “Famous” video and Pokemon Go) and scary-flat voice. His new film takes an impossibly tall order as its subject: the Internet. There’s no way “Lo and Behold” will ever hold up to the Herzogs where he tackles a much smaller, termite-sized subject: a German Helen Keller and a deaf-and-blind hospital in “Land of Silence and Darkness,” a mad yet gutsy bear enthusiast in “Grizzly Man.” But there’s no denying it’s pure Herzog: a erratic, irregularly beautiful weirdie that introduces us to some pretty exciting outer-denizens of the world.

With “Lo and Behold,” Herzog the Hunter aims his incisive sights, shotgun-style, at the World Wide Web. The buckshot he uses is his own, raw experience: as a guerilla filmmaker, as a self-proclaimed un-user of the Internet (he only keeps a simple cell-phone that’s turned off most of the time) and as a soldier in the fight against corrupt consumerism. (“We need real war against commercials, against Bonanza and Rawhide,” he once proclaimed.) The game he ends up netting is a carnivalesque parade of people from the most remote corners of the Earth. Ted Nelson, one of the original Internet pioneers, shares his ambitious ideas for an alternate Internet based upon an impossibly convoluted system of hyperlinks. (Nelson was dismissed as a madman; he thinks of himself as an abstract computer artist; Herzog thinks so, too.) The Internet-hating Catsouras family grieves for the loss of their daughter Nikki in a car-crash, the grief magnified when her death-photos go viral on the Internet — before they even know she’s dead. Elon Musk wants to colonize Mars (and, of course, Herzog volunteers to go). And a separate colony on Earth has formed, populated by radiation-allergic folks who can’t live wherever WiFi signals are transmitted. (Quite an eclectic bunch, isn’t it?) The goal is to crowd “Lo and Behold” with as many different, interesting folk as possible, thus replicating the Web’s tentacle-like reach, its glorious randomness.

***

Before proceeding with the film review, we’ve got to talk a little about the filmmaker. No small feat, since Herzog is a squirrely cat to pin down. The sheer breadth of topics among his 70+ feature films, documentaries and short films defy any logical paths or set formulas by which we can analyze his work. With Herzog, you genuinely can’t tell where he will go next. And yet, his films look and move like no one else’s. They are singularly his. What gives?

The Herzog genre is hard to define, but there’s a few set features to all of them. They take excessively eccentric subjects (the deaf-and-blind, cave paintings, burning oil fields in Kuwait, kid soldiers fighting in the Nicaraguan Civil War) and treat them with the disquieting casualness of an evening walk with your cousin’s cute dog.

They spit in the face of anyone who tries to distinguish between what’s “real” and what’s “fictional” in them. Herzog is notorious for refusing to admit there’s a difference between the two. Indeed, watching his films makes you question your own sense of real and unreal, thus making you question your sanity. Each of Herzog’s fiction films inches one step closer to Jean-Luc Godard’s vision of narrative cinema: “All a movie is, is a documentary of its actors.” In the disorienting and abrasive “Even Dwarfs Start Small” (1970), Herzog asks the question: What would happen if a cast of dwarves and I created our own society away from anything recognizably mainstream? “Aguirre: The Wrath of God” (1972; Herzog’s most famous film) is what happens when you put an insane and megalomaniac asshole (Klaus Kinski basically playing himself) in a jungle, dress him up as a Spanish conquistador and watch heads butt between him and his German lackeys. “Fitzcarraldo” (1982) shows exactly how Herzog and Kinski convince Amazonian natives to transport an entire boat across a mountain. (Presumably, with no union contract.) Reportedly, one of the Amazonian extras came up to Herzog during production and asked for his blessing to kill the mad Kinski, since Kinski’s hot-head behavior incurred the wrath and ire of everyone on the set. And so on, and so forth.

Likewise, Herzog’s “documentaries” veer remarkably away from factual truths, carried away with fantastical imagery often tangential to the main subject. “Cave of Forgotten Dreams” (2010) infamously ends, not by trying to summarize the essence of the cave paintings we’ve been discussing for the past 100 minutes, but by ogling a family of baby crocodiles swimming merrily in a nearby aquarium. “Grizzly Man” (2006) has some odd, stilted interviews with the former girlfriend of the titular Bear Lover, Tim Treadwell. Later, Herzog, the girlfriend, and Treadwell’s mustachioed pilot (the last living person to see him alive) stage an ash-spreading funeral near the campsite where Treadwell was mauled to death by a bear. It’s hard to forget this awkwardly-framed band of outsiders —the laconic German filmmaker, the tree- and hip-hugging hippie and the Ron Swanson outdoorsman — as they spread Treadwell’s ashes in a non-parody of the finale of the Coens’ “Big Lebowski” (1998).

Depending on your sensibility, you’ll either be frustrated or downright elated with Herzog’s loose stance on fiction and reality.

The Herzog film casts a hypnotic spell by using a smorgasbord of unusual techniques. He uses meditative repetition; “Fata Morgana” (1971) opens in scratched-CD time as Herzog makes us watch a plane land ten-plus times in a row — each landing more important and symbolic than the last. (How? Who knows.) He gets super close to his subjects, his camera swimming around them as if it were a baby looking at stubby squids floating in the ocean’s depths. He lets a camera linger for far longer than necessary on images — a nightmare for an editors, but strangely dazzling for the viewer. Of particular note is the heartbreaking final images of “Land of Silence and Darkness,” his 1971 documentary on the deaf-and-blind. (“Of all my films, this is the one I want to be available to audiences the most.”) Here, Herzog films a man born deaf and blind, unable to communicate in any way (unlike Fini Straubinger, the German Helen Keller), nestling up to a tree, caressing it, trying to communicate with the cameraman and Herzog. It’s perhaps the most awe-inspiring and tear-inducing moment in all of Herzog’s cinema. Here’s a person trying to break through an unimaginable darkness in real time.

Above all, Herzog refuses to judge any of the characters in his real-life dramas. If anything, he tries to enter the interiority of his characters’ minds. The most moving example, again, is the ending to “Land of Silence and Darkness,” a film whose veins rush with the lifeblood of an observant human who wishes to know the perspective of someone with neither the privilege of sight nor sound. Is the mind total darkness, Herzog wonders? Or does a light, however dim, manage to shine through? What does it look like to the fortunate, the privileged among us? To us, as to the tree-hugging deaf-blind man, this touching finale is an emotional breakthrough. The breathtakingly simple shots of “Land of Silence and Darkness” — lots of Malick-queasy shots of the camera nuzzling up to the deaf-and-blind subjects — are not exploitative in the slightest, though they may seem so. Rather, it’s Herzog’s unusual way to understanding, grappling, faithfully translating the experience of the amazing people he photographs.

No wonder one of his favorite books is J.A. Baker’s “The Peregrine,” a 1967 “nonfiction” book where the author’s mind seems to become one with the hawks he’s tracking. (Herzog recently gave a talk about this book at Stanford.) Baker and Herzog both make the case for a supercharged use of poetic license, far beyond comfortable levels. In this way, the “ecstatic truths of the world” (Herzog’s words) make themselves visible to us. Infamous for his deadpan dismissals of anything that reeks of “accountant’s truth” and “dull imagination,” Herzog is a completely different person behind the camera. An open-hearted man who wishes to share his experiences with the world, Werner Herzog uses the film medium to make us consider the world in a jazzed-up Dutch angle.

***

All these techniques are employed in the beautiful “Lo and Behold,” a film as batty as its creator. The awkward zooms, lack of a definite documentary goal and relaxed flow lends it its manic soul.

Some of the folks Herzog interviews for “Lo and Behold” recall the endlessly fascinating, non-urban folk in Errol Morris’s early documentaries (“Gates of Heaven,” “Vernon, Florida”). Ted Nelson, a self-proclaimed “computer artist,” works himself up in a frenzy as he explains his complex theories, completely forgetting he’s being interviewed or that there’s a camera in front of him. There’s also the unforgettably stilted straightness of the Catsouras family, whose daughter’s tragic death-photos were sent to the father via email. Herzog’s occasional hatred for humanity is relentless in this segment. He’s always had a repulsed fascination with man’s depravity, and it seethes in every shot of this jaded family. Even when they start stuff like the Internet is “the manifestation of Evil” and “the Antichrist,” we’re too far into their story to really back out. Herzog neither mocks nor glorify this broken family. He simply observes them with a hard-and-soft lens, searching for the human soul that extended use of the Internet threatens to eradicate. It’s a genuine and noble thing to look for.

Despite his fame, Elon Musk gets the common-man treatment, too. Herzog cares quite little about Musk’s reputation and what he can concretely do. He’s more interested in the impossible dreams Musk has. As the Internet grows more sophisticated, Musk is first in Herzog’s mind, a pioneer whose dreams are the kind of late-’60s-era space-race-dreaming he believes makes humans great.

But there’s a special place in Herzog’s heart for the quasi-mountain folk who have been banished by the encroachment of the Internet. There’s something disturbing in hearing their story, people who we forget about in our normalized conception of a Connected World. The radiation-allergic community — sitting around all day playing bluegrass on the banjo, Vera-Lynn-from-the-end-of-“Dr. Strangelove”-style — restores Herzog’s faith in humanity, but also confirms his bemused disgust with it. As we become more attached to the Internet, it becomes almost an addictive high from which we can’t escape. Herzog, a loosey-goosey Luddite, champions a break from the Internet, stepping back to see how far we’ve come but also how much we’ve got to lose.

For its sheer scope (impossible to keep under 100 minutes), Werner Herzog’s soulful investigation of the Internet will obviously be unsatisfying for many. But for what it is (rogue auteur takes on Silicon Valley), it’s damn thought-provoking. Many people will be turned off by its seeming self-parody. Don’t be! It’s very minor Herzog, never reaching the sustained, ecstatic heights of his greatest work (“Land of Silence and Darkness,” “Aguirre”, “Woodcarver Steiner,” “Lessons of Darkness,” “Gesualdo: Death for Five Voices,” “Grizzly Man,” among many others I haven’t seen yet). But the success of a Herzog depends upon how engaging and thought-inspiring it ends up being. In that sense, “Lo and Behold” showcases Herzog at his finest.

***

“Lo and Behold, Reveries of the Connected World” opens at the following Bay Area locations: the Landmark Clay in San Francisco, the Landmark Shattuck in Berkeley, the Camera 3 in San Jose, the Christopher B. Smith Rafael Film Center in San Rafael and Osio Cinemas in Monterey.

Contact Carlos Valladares at cvall96 ‘at’ stanford.edu.