By late August, Michele Dauber’s media requests have thinned — but only compared to the couple hundred interview requests she received in the early weeks of June. That’s when she launched her campaign to unseat Judge Aaron Persky ’84 M.A. ’85, who gave former Stanford student Brock Turner an unusually light sentence of six months in county jail for sexual assault.

The Stanford law professor’s interviews are interrupted by more requests for interviews. Often, she is asked to comment on the latest school sexual assault case surfacing in a summer of heightened public scrutiny: Today it’s 18-year-old David Becker in Massachusetts (sentence: no jail, two years on probation). Dauber’s effort to recall Turner’s judge has pushed her to the center of an explosive international movement to combat sexual violence, and her opinion is in high demand.

“I know you’ve been trying for a while to reach me,” she tells a caller that morning in her office, just after a live interview with ESPN. “Call me back in 10 minutes and I promise I’ll be able to talk.”

For Dauber, furor over the Brock Turner case has given enormous momentum to an issue — campus sexual assault — that she’s dedicated herself to for years in academic, political and personal capacities. She’s created a Stanford course devoted to the subject. She’s helped overhaul University policy. And she’s become a well-known resource for sexual assault victims on campus looking for an advocate.

“[Dauber] is relentless in making a difference around sexual assault, and I mean that in a positive way,” said Shelley Correll ’96 Ph.D. ’01, a sociology professor and member of Stanford’s current sexual assault task force. She collaborated with Dauber on, among other things, a letter suggesting revisions to the task force’s initial draft policy on dealing with campus sexual assault.

“When I’m working on something with her, she will text me, text me, text me,” Correll said. “My phone is kind of blowing up. She’s moving at 100 miles an hour, and by the time I respond, she has a new idea. Her energy is hard to even put into words.”

Path to Stanford

Dauber, Frederick I. Richman Professor of Law, was not always drawn to academia. In fact, she stopped attending school after ninth grade. She grew up in Pennsylvania, and later Indiana, reading voraciously — science fiction, adventure stories, anything except Jane Austen (“bo-ring”) — but caring little for her classes. In Dauber’s words, she “just wasn’t good at school,” even though years later she would graduate from Northwestern’s Pritzker Law School with high grades.

Further complicating those high school years, Dauber became a mother at 17, which caused a rift in her family. She lived on her own in Indiana before moving to Chicago at 18 or 19. She returned to school five years later at the University of Illinois at Chicago majoring in social work; she too was low-income at the time and interacted often with social workers. Dauber waitressed and worked other miscellaneous jobs on nights and weekends. She spent a few months homeless.

Studying social work, Dauber began to wonder what the most vulnerable people in society could use most. A grant to conduct research on domestic violence and child custody convinced her that they needed lawyers. Her interest in the law world began with an issue she’s still grappling with: violence against women.

“Basically, getting beaten up in front of your kid was a form of neglect,” Dauber said. “So instead of trying to work with the mother to keep her children with her, the state would take her kids away and put them in foster care.”

By the time she entered Northwestern for a joint J.D. and Ph.D. in sociology on a combination of scholarships, loans and financial aid, Dauber herself had three kids to care for. Her earnings from a lucrative summer job at a corporate law firm went toward a minivan. She said her main thinking upon taking a position partly based in Washington, D.C. was, “My kids will get to go to the Smithsonian every day, and that’ll be awesome.”

But Dauber found most of corporate law either dull or distasteful. She decided she would become a public interest lawyer or professor. After clerking briefly for a famously liberal judge and finishing her dissertation as a fellow at the American Bar Association, she moved to Palo Alto in 2001 to teach at Stanford.

Teaching

Stephanie Pham ’18 always turns to the same anecdote when asked about Dauber’s teaching style. Last fall, while on a D.C. field trip for Dauber’s three-week Sophomore College (SoCo) class on sexual assault, Pham witnessed the professor leaping over chairs at the end of a congressional hearing in the hopes of snatching her students just a few minutes and maybe a photograph with Jackie Speier, a Congresswoman known for advocating for sexual assault victims. In the end, Dauber scored Pham and her classmates an hour in Speier’s office.

“She’s such a determined woman,” Pham said, laughing. “I’ve never seen a professor jump over chairs before.”

Dauber said although she “loves” Stanford and her students, the excitement she felt upon arriving as a new teacher has tarnished over the last few years with the sense that her criticisms of sexual assault on campus have put her at odds with the University.

“The hardest part of the job is feeling like the University is mad at me because I don’t think they’re necessarily always doing a good job,” she said. “Stanford is not an organization that tolerates criticism of itself very well.”

Dauber’s outspokenness and reputation on campus means that she is approached for support by students she may barely know.

When Leah Francis ’14 sought to appeal the outcome of her University-adjudicated sexual assault complaint, friends directed her to Dauber, and Francis even lived at Dauber’s house for a time when, according to Dauber, she did not feel safe at Stanford. When a student heard about a possibly roofie-related hospitalization at a fraternity event, he brought it up in Dauber’s Sociology of Law class.

Just after Stanford announced it would ban hard alcohol from undergraduate parties this year, a policy that Dauber publicly criticized as raising health and sexual assault risks through binge drinking behind closed doors, a student emailed her simply to express his frustration with the administration’s decision. Dauber responded with a single line: “They’ll never change it.”

“I know who I would go to if I had an issue with the University,” said Alex Young ’19, who took Dauber’s SoCo course this fall.

Last fall, Dauber’s SoCo students chose a variety of formats for their final projects, from a research paper to a live performance to a 34-page manual on sexual assault aimed at Stanford employees. Some students, such as Pham, held signs and distributed fliers with statistics and other information on sexual assault during the class’s overlap with New Student Orientation (NSO). Dauber considers the students’ activities last year “community education.”

“We wanted to do a very peaceful distribution of information,” Pham said, noting that Dauber had the class review University guidelines such as “free speech hour” in White Plaza. “We didn’t want to break any rules.”

One student, who wished to remain anonymous, broke Stanford’s policies by placing some of his fliers, addressed to parents, on car windows. University employees arrived within half an hour to stop him, and the dean of undergraduate advising and research sent him an email saying that putting fliers on cars as well as handing them out in general were not allowed on the first day of NSO. When the student pointed out over email that Stanford prohibits only “student organization recruitment or tabling” on move-in day and asked to see the specific rule at issue for non-recruitment placement of fliers or placement by individual students, he did not get a reply.

“To be honest, he was engaging in First Amendment protected political speech with the best of intentions, and I think it was handled in a very unfortunate way,” Dauber said. “Staff could have just calmly directed him to White Plaza and not made a big deal out of the fact that he made an honest mistake.”

Stanford spokesperson Lisa Lapin said the fliers’ distribution method, not their subject matter, was problematic.

Criticizing Stanford

Dauber sees criticizing the University as part of her professorial duty. In her view, not enough faculty disagree openly with Stanford, and she was disappointed when, just recently, professor friends who oversee dorm life as resident fellows (RFs) did not join her in speaking out against the University’s tightening of hard alcohol. She sent them prodding emails, recalling that many of them opposed a hard alcohol ban when administration floated the idea in a meeting of RFs in March.

“Whatever the reason, it is sad to me,” she said later, referring to other faculty members’ relative quiet on the alcohol changes.

Dauber did not speak out in highly public conflicts with the University until 2014, after helping then-student Leah Francis appeal for harsher sanctions against a fellow student Stanford found responsible for sexually assaulting her off campus, in Francis’ home state of Alaska.

The accused student received 40 hours of community service and a five-quarter suspension, later extended to two years. The suspension would begin after the then-senior graduated, allowing him to return to Stanford for graduate as planned if he chose. Francis, who argued unsuccessfully that Stanford should expel her assailant, went public with her story and blasted the punishment as a “gap year” in an email that was circulated widely among students.

Expulsion for sexual assault is possible but almost never employed at Stanford. Many studies estimate that one in five women will experience some form of sexual assault during her college years, but from 1997-2014, the University expelled only one student for the offense. In that same time period, the University received 280 reports of sexual assault, conducted 14 hearings and found 10 students responsible. (Hearings are only possible when the accused is a Stanford student, and victims can choose whether they want to go through the process).

The majority of those hearings and sanctions came after a large reform of Stanford’s sexual assault adjudication method, dubbed the Alternate Review Process (ARP), which began piloting in 2010 and was replaced by the Stanford Student Title IX Investigation and Hearing Process this February. Dauber gave input on that new system as a member of the Sexual Violence Advisory Board and, from 2011-13, co-chaired the Board of Judicial Affairs that revised and implemented it.

The ARP sought to increase victims’ participation in Stanford’s hearing process with a new judicial procedure specifically for sexual assault. Dauber and others argued that the existing process set forth in the Student Judicial Charter of 1997 was better suited to offenses like cheating and that sexual assault victims were wary of an old process in which, for example, they could be cross-examined directly by the accused.

“The gap is the problem — the gap between adjudicated assault and reported violations,” Dauber told this year’s SoCo class. “This gap is not just Stanford’s problem; it’s everybody’s problem. Every university is dealing with this.”

Under the ARP, reviewers, rather than the accused, examined the victim. The process involved private interviews rather than one combined hearing, and both parties could appeal the outcome of a case. In order to comply with 2011 federal guidelines, Stanford also lowered its standard of proof needed to find a student guilty of sexual assault, from “beyond a reasonable doubt” to “preponderance of evidence” (meaning more likely than not), the bar used in U.S. civil courts. Critics say the national shift makes guilty verdicts less certain, but others, like Dauber, argue that colleges should be able to regulate their campuses and discipline their students more easily than a criminal court can send someone to prison.

By the numbers, the new adjudication system did seem to encourage victims to bring their complaints to Stanford. Stanford’s annual reporting of sexual assaults roughly doubled under the ARP. Meanwhile, the University adjudicated 11 cases in the first three years of the ARP — almost three times as many as it had overseen in the last 13 years combined.

But the ARP still drew criticism. In June of 2014, Francis’ story shot through campus. Students protested under the hashtag #StandWithLeah that the University still did not give sexual assault the weight it deserved.

As Francis became local and national news, many reporters reached out to Dauber — not because of her role in Francis’ appeal, Dauber said, but ironically because the University had previously touted her as a sexual assault expert for her work on the ARP. Dauber sided emphatically with Francis.

“I really couldn’t be more disappointed with the way this happened, and it certainly isn’t what I had in mind with the drafting of the [review process],” she told the Mercury News at the time.

How to move forward

When the University convened a sexual assault task force that summer to review policies, Dauber was not on the committee. Administrators told her the group was full.

“I am disappointed because I feel my experience would be beneficial,” Dauber told the Palo Alto Weekly that summer. However, Dauber emphasized now that she does not view her omission negatively and is glad that other Stanford faculty have emerged as leaders on sexual assault through the task force.

Regardless, Dauber still helped shape Stanford’s policies. The task force solicited community-wide feedback on a draft process last fall that, among other changes, made expulsion an expected sanction for sexual assault (defined by Stanford as penetrative or oral in nature). The new process that began piloting this February incorporated a number of concerns from Dauber’s letters on the subject, including one she wrote with Correll and three other faculty members.

“Sometimes I think it looks like people are fighting with each other in kind of a hateful way, but I don’t really read it in that way,” Correll said about conflicting views over Stanford’s sexual assault policies. “I think what we have are a lot of people who think this issue is very important and disagree about how to move forward.”

Dauber still believes that Stanford defines “sexual assault” too narrowly: Unlike many peer colleges, Stanford deems non-consensual contact besides penetration or oral sex by force or incapacitation “sexual misconduct,” in order to differentiate expected sanctions. Dauber also believes the new process makes conviction too difficult by requiring the unanimous decision of a three-person panel.

So far, the pilot process has received positive feedback, particularly for providing up to nine hours of free legal assistance to both parties, according to Lauren Schoenthaler, a task force member who filled the new position of senior vice provost for institutional equity and access this year. However, the task force is still assessing the system and may make further changes.

Following the Turner case, Stanford has allocated an additional $2.7 million in sexual violence programs to its budget for this year. It debuted its new student-led sexual assault training in dorms. And in September, Schoenthaler publicly apologized to Brock Turner’s victim on behalf of the Stanford community, in a move that Dauber lauded as an “auspicious start” for both Schoenthaler and Stanford’s new president, Marc Tessier-Lavigne.

Even so, Dauber is disappointed with much of the University’s approach to sexual assault.

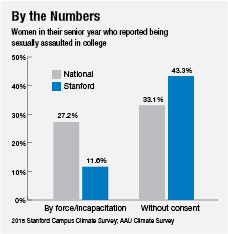

She still wishes the University would redo its 2015 Campus Climate Survey on sexual assault to align with the Association of American Universities’ survey. Speaking to the Huffington Post, Stanford spokesperson Lapin alluded to Dauber in April as the survey’s “single primary critic,” but later some 30 other faculty letter-signers and a campus-wide student referendum would also lend their support.

Dauber also wishes the University would take a harder look at fraternities, pointing to Harvard, which effectively abolished Greek life this year. Her concerns go beyond Brock Turner, who did not belong to a fraternity but whom two witnesses spotted on top of an unconscious girl by the dumpster outside a Kappa Alpha party last January. Dauber also cites, for example, 2014 revelations about sexually aggressive emails sent by Snapchat cofounder Evan Spiegel ’12 when he was social chair of Kappa Sigma fraternity. Where others praised Provost John Etchemendy’s and Kappa Sigma’s disavowals of the emails, Dauber sees a dearth of systemic change.

“Harvard’s been willing to take this on,” she said. “We haven’t.”

Vice Provost for Student Affairs Greg Boardman pointed out over email that the Provost also in 2014 issued a new policy emphasizing that fraternities could lose on-campus housing for violations, as Sigma Alpha Epsilon (SAE) did that year, and that Residential Education and other offices have developed sexual violence training for leaders in Greek life.

Finally, Dauber sees more “pedestrian” changes that she believes could make University-sanctioned fraternity parties, like the one outside which Turner committed his assault, safer: adding private security and improving lighting or installing video cameras outside residences so that future incidents might have the sort of footage that Turner’s prosecutor requested. Lapin said the University cannot discuss cameras for security reasons but is currently reviewing lighting around Kappa Alpha — although she noted it was sufficient for two Stanford students bicycling past at night to apprehend Turner.

The Turner sentence

Dauber admits she’s not unbiased when it comes to Turner or Judge Persky, whose sentence for Turner drew accusations that the judge did not take sexual assault seriously and let a white, elite athlete from his alma mater off easily. Turner’s anonymous victim, Emily Doe, is a family friend of Dauber’s. Dauber knew her as “brilliant,” “artistic” and “extremely responsible and mature.”

“Parents would say, oh, well, if she’s going to the party, it’s going to be fine,” Dauber said. “She’ll take care of the others.”

Then Dauber discovered that Doe was a victim of a crime she had fought on campus for years. For Dauber, first, there was anger. Then, a grim feeling: “If it could happen to her, then it could literally happen to anyone.” Finally, resolve.

“I was like, ‘It’s on,’” she recalled.

That resolve resurged when Dauber heard Persky’s June 2 sentencing. Turner faced up to 14 years in prison. Persky followed the probation officer’s recommendation — as is his custom, according to an Associated Press analysis of his record — and gave Turner a punishment within the law but far lower than the six prison years prosecutors sought. Persky cited a number of mitigating considerations including Turner’s youth, lack of criminal history and the “severe impact” a harsher sentence would have on Turner. Within about a week, various petitions to remove Persky from the bench garnered over a million collective signatures.

But removing Persky from office requires much more than an online petition. Because the judge is running unopposed this November, his opponents must get the formal signatures of about 20 percent of registered voters in Santa Clara County, Persky’s district, to get a recall measure on the ballot for popular vote.

Enter Dauber, who believes not only that Persky got the Turner sentence wrong but that his record indicates a lax attitude toward sexual violence and violence against women. Her Twitter account blasts other seemingly light sentences: four days in county jail for possession of child pornography, 12 weeks of weekend-only jail for domestic violence causing “serious bodily injury.”

Dauber began talking to fellow members of Progressive Women of Silicon Valley, a group that fundraises primarily for female senate candidates. The official Committee to Recall Judge Persky coalesced under her leadership.

“We’re pulling the robe off a bit and saying hey, these are just men,” Dauber said. “And if they’re going to refuse to treat these sex crimes like the serious crimes they are and say boys will be boys … they will be held accountable to the people they serve.”

A recall will be long and costly. As of the end of August, with over 2,000 individual donations, Dauber’s group was about halfway to its first fundraising goal of half a million dollars by the end of the year. Most of this money will go toward professional signature collection at around $5 per name, starting in April when a post-election “blackout period” against campaigning ends. The recall movement seeks another $600,000 by August 2017 to cover advertising and direct mail.

The law community both at Stanford and at large is divided over Dauber’s cause. In June, 53 recent graduates of Stanford Law School wrote an open letter to the professor saying that, while they disagree with Turner’s sentencing, they believe a recall could discourage other judges from showing mercy when appropriate and could threaten judicial independence by removing a lawful judge on the basis of popular opinion. Thirteen Stanford faculty were among 46 law professors across California who signed a similar public letter in opposition.

“The recall movement seeks to make Judge Persky and all other California judges fear the wrath of voters if they exercise their lawful discretion in favor of lenience,” the letter reads, warning of a slippery slope where special interest groups can leverage money or high media coverage to retaliate against unfavorable verdicts. Multiple Stanford faculty involved declined to comment, saying the statement speaks for itself.

In response to critics, Dauber argued that while judicial independence is important, it relies on a lack of bias.

“When people feel that they don’t have access to an unbiased decision maker, they don’t just lose faith in that particular tribunal,” she said. “It erodes their confidence in the entire legal system.”

Furthermore, she said, all superior court judges in California are elected and therefore already accountable to popular opinion; the recall only forces that customary public review to take place sooner (given that he is unopposed this fall, Persky is not up for regular election until 2022). Research finds that judges rule more harshly near election time, but Dauber said there is no evidence that rare judicial recalls heighten this phenomenon.

“I don’t like when [criticism of the recall] verges over into accusations that somehow we are doing something wrong or bad and that the voters don’t have the right to call this reelection, which we absolutely do,” Dauber said. “This is democracy. We simply opened the book of the California constitution.”

In September, Persky voluntarily transferred out of his Palo Alto criminal court and into a civil court in San Jose. That means that, at least for now, the embattled judge will not hear criminal cases. But the recall movement continues. Dauber argues that Persky could transfer back to criminal court in the future and that there is no room for Persky’s mentality in a civil court either — in sexual harassment suits, for example.

And in the end, Dauber said, the recall movement is about more than one judge and his future cases. For Dauber and her supporters, it’s also about sending a strong message condemning sexual assault across the country. New legislation and the flurry of campus assault cases breaking news suggest that momentum is already underway.

“We’re gonna win this recall,” Dauber said. “But even if we lose, we’ve already won.”

Statistics on sexual assault reports, hearings, findings of responsibility and expulsions from 1997-2014 come from Faculty Senate meeting minutes from May 2, 2013 and the 2015 article “Untangling the Knot” in Stanford Magazine. Statistics on Stanford’s pre- and post-ARP annual reporting of sexual assault come from the University’s 2010-12 and 2013-14 campus crime statistics, as well as the above Faculty Senate minutes.

Contact Hannah Knowles at hknowles ‘at’ stanford.edu.