“Every 28 hours in America, we lose a piece of our soul.”

This is just one of many of the deeply poignant lines from Stanford students’ performance of “The Every 28 Hours Plays: A Staged Reading,” an event which featured a series of poetic, haunting narratives intended to raise awareness on the Black Lives Matter movement. These vignettes covered a variety of different social issues, ranging from police-victim interactions to intimate familial strife brought on as a result of police brutality in the United States.

“The ongoing oppression of, and violence against, people of color in our country demands continued attention,” said Rebecca Struch, producer of the plays and program associate at the Stanford Arts. “I believe the theater provides a unique opportunity to come together across our differences, engage in dialogue about these experiences of oppression, and to commune toward collective action. Each of these one-minute plays serves as a ‘heartbeat’ of a growing movement for change.”

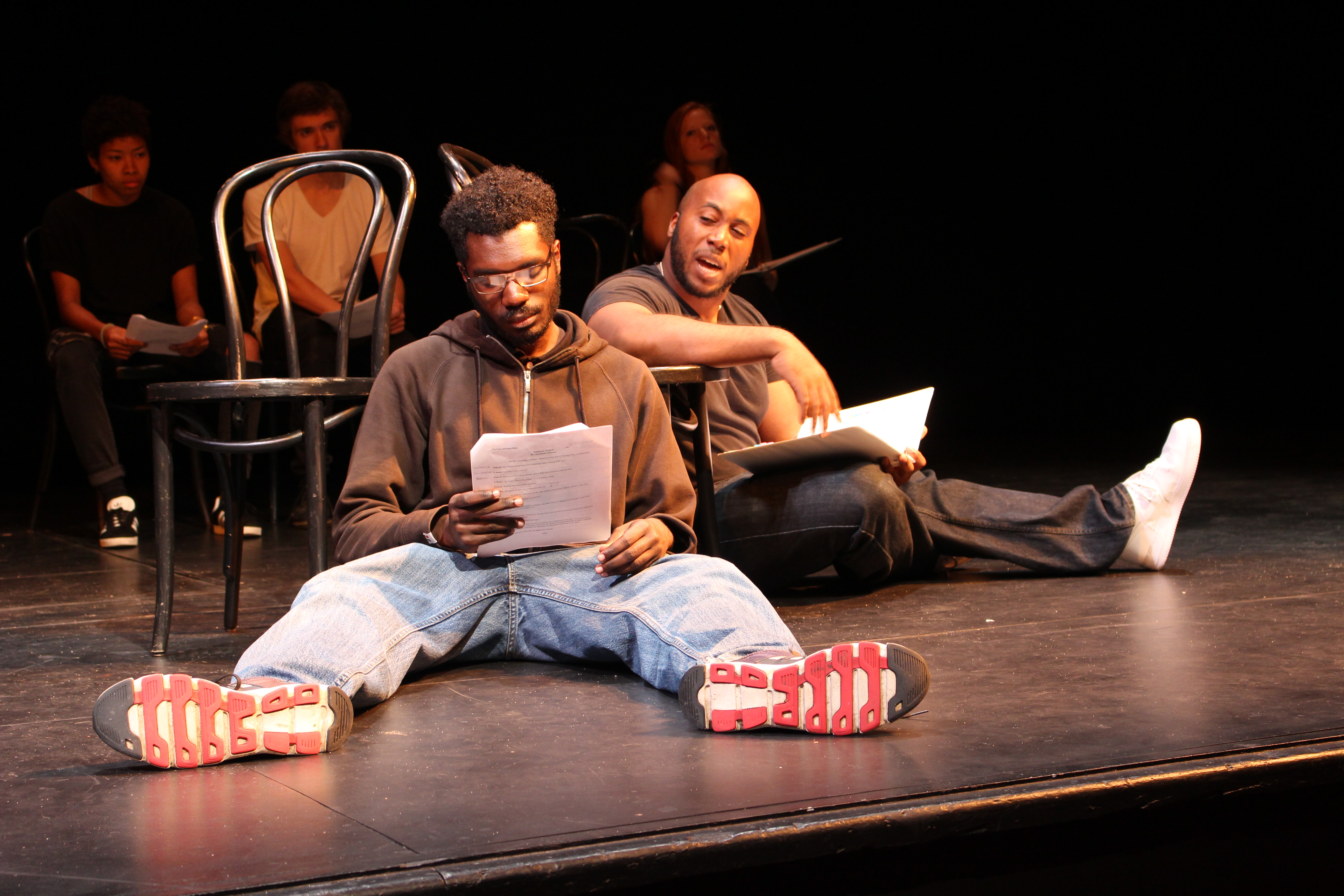

The 22-person cast welcomed a sizable audience free of charge into Pigott Theater after its only rehearsal the day before. The two-hour production was a collaborative effort organized by members of Stanford Arts Institute, the Institute for Diversity in the Arts, Stanford NAACP, the Black Student Union, the Black Feminist Collective and the Black Men’s Forum.

Each one-minute scene provided a raw, organic glimpse across an enormous scope of lives impacted by racism and police brutality through jarring discourse between cops, victims, members of victims’ families and everyday people. A mixture of single-character monologues, duo performances and small group performances highlighted interactions between members of the police force and individuals identifying as transgender, Black, Hispanic and more. In all, the vignettes served to humanize the African-American body, forcing the audience to question the true meaning of diversity and equality in America.

Not just about being moved

His sobs grew harder to stifle, but the names of slain black Americans kept coming.

“To hear my fellow actors and actresses falling, to hear their bodies thud against the ground, and then have to read those names, it was really tough,” said Christopher Cameron, second-year graduate student and actor in the plays. “When I said ‘Trayvon’ – because I remember when that happened, I went to [Carnegie Mellon University] with my hoodie on and he is from South Florida and he was killed around Central Florida near Orlando – that’s when it was no longer acting.”

Performing also allowed Cameron to outlet his emotions about being a minority for the first time in college, emotions that had accumulated over the past four years.

“Play Two? I relate to it. Play Three? I relate to it. Play Four? I relate to it. Play Five? I’m in it. Play Six? I relate to it. Play 35? I relate to it,” Cameron said. “It was starting to get me upset and I even started breaking character on stage while sitting up there starting to react to more and more.”

For both viewers and actors alike, it was a gripping night, with intimacy juxtaposed with unease, laughter mixed with disquiet, simplicity and convolution. More than anything, though, it was a transformative evening of reframing perspective.

In describing the desired impact of the play, director and actor Stewart Gray III ‘18 said, “I don’t hope that people are merely moved, because I feel that too often we are ‘moved.’ Especially for black bodies and black pain, where that can be a kind of spectacle for some people, where black pain is something that’s viewed as entertainment and not so much as an awakening – an awakening to go and to act in the capacity that you are needed.”

More personal connections surfaced in the moderated post-show discussion, which allowed audience and cast members to reflect upon the plays. Cast member Adorie Howard ‘17 questioned why it takes a play to generate compassion towards victims of violence.

“I’m really, really tired and I’m 21 years old,” Howard said.

What it entails for Stanford Students

About its relevance to Stanford specifically, one of the co-producers Trevor Caldwell said before the performance that he hoped students could think outside of the Stanford bubble by listening to the narratives about police violence that may not manifest on daily campus life.

“Theater is such a great opportunity to come together and process something that’s really complicated and hard to talk about,” said Struch. “This project in particular is useful for Stanford and the Stanford community because each play operates like a little heartbeat. It’s just one minute, it’s just a glimpse into a particular angle on civil rights or racial justice in America.”

Following the event, audience member Eni Asebiomo ‘18 said, “At Stanford, it’s so easy to just forget about the issues that are going on. This whole thing [brought] me back to some things that I’ve not forgotten, but not had to think about for a really long time – and I think it’s just so powerful,”

Fellow audience member Dane Stocks ‘20 agreed, citing that the experience of viewing the play encouraged him to be a more active supporter for social justice in the United States.

“Up to [tonight] I feel like I’ve been really passive,” says Stocks. “Being [at Stanford], it isn’t much better because there is a bubble. But whenever I’m around experiences like this, it makes me want to make actual change in not just how I think, but how I act.”

The importance of action

At the end of the production, the entire cast gathered on the small stage, and, in a scene resembling a vigil, Cameron read aloud the names of people who lost their lives as victims of police brutality. As the last name was spoken, the room stood still as both the cast and audience came together for a collective moment of silence for those individuals.

Eventually, the silence broke way to thunderous applause that charged the small theater with the emotional gravity of the moments that had just been shared on stage. As producer Rebecca Struch appeared on stage to open up the floor for anyone who wanted to share a word about their experience, words like “mourning,” “solidarity” and “painful” fell from audience members’ mouths.

“It is easy to become numb in the face of constant oppression, either as one who experiences that oppression or one who witnesses,” said Struch. “The students, faculty, staff and audience members who have come together for this ‘rapid-response’ theater are actively resisting the lure of silence and isolation in order to heal.”

Contact Courtney Gao at cgao20 ‘at’ stanford.edu and Claire Wang at clwang32 ‘at’ stanford.edu.