As Stanford enters its 125th year as an university, Green Library is hosting a new exhibit that explores the forerunners of campus activist organizations and the causes that Stanford students advocate today.

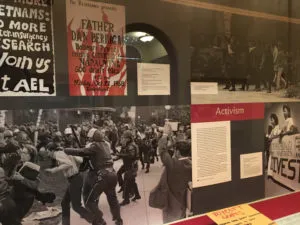

Named “Stanford Stories from the Archives” (Stanford Stories), the exhibit features diverse aspects of student life ranging from student traditions to research, including a section entirely devoted to activism. The civil rights movement, beginning in the 1960s occupies a special place in the displays, alongside present-day causes such as Fossil Free Stanford and Black Lives Matter.

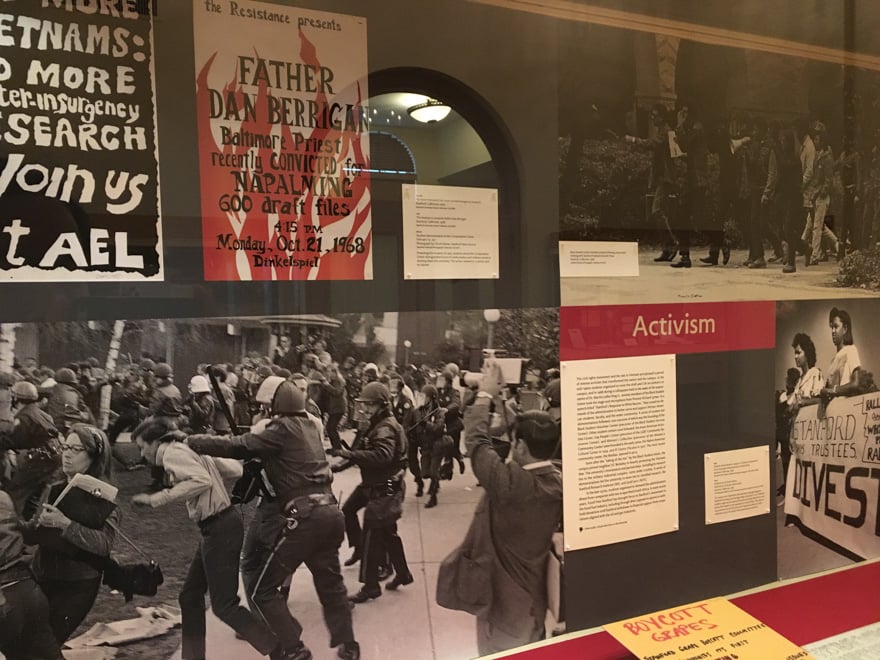

From the archives: civil rights and anti-militarism

Stanford Stories takes the viewer back to the 1960s, revisiting the sit-ins and non-violent protests of the civil rights movement that have echoes in present-day events. For instance, a major portion of the exhibit is dedicated to the proactiveness of leading civil rights organizations on campus, such as the Black Student Union (BSU).

“The civil rights movement … precipitated a period of intense activism that transformed the nation and the campus,” one exhibition panel read. “In 1968, during a colloquium held in the wake of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., 70 members of the Black Student Union took the stage and microphone from Provost Richard Lyman.”

BSU activity resulted in tangible change for students who identified with minorities or marginalize identities on campus. Four days following King’s assassination, 70 BSU members demanded that the University make 10 new commitments toward black and other minority students, such as recruiting more black faculty members. The University fulfilled nine of those commitments.

As a result of the push by cultural and gender minority organizations, the 1970s saw the founding of the Black Community Services Center, Asian American Activities Center, Gay People’s Union (now the LGBT Community Resource Center), Women’s Collective (now the Women’s Community Center), Native American Cultural Center and El Centro Chicano, which continue to serve the student population today.

The 1960s and 1970s also saw vocal — and at times violent — opposition to the Vietnam War, especially Stanford laboratories that were contributing to war-related research.

“From 1970 to 1972, protests, demonstrations, sit-ins and other political activities sometimes turned violent as students openly clashed with police and campus administration in an effort to combat the war at home,” the exhibit read, noting the irony of the occasionally violent approach to pacifism.

For instance, over a two-day period in April 1970, students reacted to the news of the American intervention in Cambodia with intense demonstrations that saw the throwing of rocks and the use of tear gas on campus for the first time. Kenneth Pitzer, President at the time, described the incident as “tragic” and resigned after just 19 months in office.

Nonetheless, the anti-war protests eventually won concessions such as the removal of academic credit for Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) courses and Department of Defense classified research on campus.

The rest of the decade saw campus activism take on a moderate tone. The change in attitudes towards conventional gender and sexual roles led to the founding of the Gay People’s Union in the Old Fire Truck House in 1970, where it remains (renamed) to this day. Another victory for activism, the ASSU voted in favor of President Richard Lyman’s 1972 proposal to remove the Stanford Indian mascot out of respect for the Native American community.

Present-day continuities

Today, student groups that represent a spectrum of issues and identities ranging from civil rights to faculty diversity continue to impact the University by forcing the administration and the entire student body to address difficult questions about justice and equality.

Over the years, community organizations have advocated for the identities they represent in different ways, beyond campus-wide activism. BSU co-president Helen Gambrah ’17 highlighted the organization’s importance in providing “healing spaces and support,” in addition to openly raising issues such as police brutality.

“When you look at activism, [you look] at different perspectives,” Gambrah said. “Not just the protesting but making sure that we’re here for each other and taking care of each other.”

Meanwhile, the questions of sexuality and gender equality raised in the 1960s and 1970s have evolved into slightly altered but equally pervasive issues about sexual violence and content.

Matthew Baiza ’18 co-founded the Association of Students for Sexual Assault Prevention (ASAP) in response to a series of nationwide and Stanford-specific incidents related to sexual violence and sexual assault adjudication on campus.

“In ways, the University and administration in particular have taken good steps in regards to education this year, [such as] what the SARA office is doing with the peer program, [but] that’s always the point of being involved as an activist: You always want there to be more done,” Baiza said.

Student activists’ efforts to confront difficult issues head-on continue to meet with their share of controversy today. For instance, Stanford Stories also featured the blocking of the San Mateo Bridge on Jan. 19, 2015. Students protested on the bridge in support of the Ferguson Action National Demands for local law enforcement reform after 18-year-old Michael Brown was shot unarmed by a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri. The incident led to the arrest of 68 students out of the nearly 100-strong group that took part in the regional protest.

Student participants in the protest declined to comment when contacted. However, Baiza had a philosophical take on the push and pull between the administration and the student activists who seek change.

“I think what we need to understand is that the administration has a specific incentive structure, and a lot of times the incentive is not to address the concerns current students are raising, but the incentive is to maintain the image of the university, financial obligations or order,” Baiza reflected.

He added, “From the student perspective, we all just want to make the world a better place than what it is right now, and that means critically addressing the issues that we feel should be addressed.”

Contact Kim Ngo at kimanh ‘at’ stanford.edu.