Note: Two surveys were used for this article; one, a poll sent out by the Stanford Daily consisting of 457 students, the other, an anonymous poll of Class of 2020 students who wrote the quotes included in the article. Responses have been edited for length and clarity.

In a few days, we will elect the next President of the United States. The television screens have been buzzing for months over the election, covering the almost theatrical campaign and all of the surprises that have come with it. Unsurprisingly, much of the political campaign has slipped into our daily conversations, brought up in classes as a modern, relevant link to the discussion or debated over lunch in the dining halls.

The night of the first presidential debate, my dorm hosted a debate party, very fairly including the favorite snacks of both the candidates, so that everyone would feel welcomed. During the debate, the entire room groaned as Donald Trump talked about his “wall” and laughed as he pursed his lips and hovered over Hillary Clinton’s shoulder.

I laughed too, but I felt a little uncomfortable. What about the people in the room that supported Trump? Were they laughing too, out of obligation? Sure, Stanford is a liberal campus, but at least 15% of the student body identifies as Republican.

The digs at Trump would continue. In a class discussion a few days later, a student concluded that anyone with a college degree would never vote for Trump — and the entire class agreed. This, I knew, was simply not true. Though I’m not a Trump supporter, I know plenty of people who do support him, many with excellent educations and multiple degrees. Labeling all Trump supporters as uneducated bigots was unfair and simply wrong.

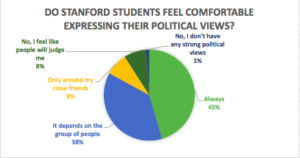

Stanford is an undeniably liberal campus. In a poll of 457 students sent out by the Stanford Daily this year, 91.5% thought that the liberal ideology was the most prominent school of thought on campus. However, only 63% of the campus population identifies as liberal. So what about the other 38% of Stanford students? Do they feel comfortable expressing their viewpoints in an environment that might not necessarily agree with their perspectives?

Answers vary. According to the same poll, 55% of students claim that “I can express my opinion but others cannot” and 16% think that they can’t express their opinions. One student shares: “I am far more conservative than the average Stanford student – many group settings are hostile towards my opinions.” Another writes, “At any group meal, [those in the] conversation will never accept any conservative view and all Trump fans are deemed idiots or worse.”

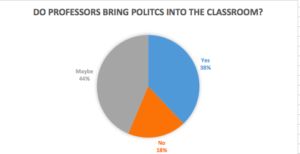

Unsurprisingly, this liberal mentality extends to the classroom as well. 41% of students think that professors bring their own political biases into the classroom, and an additional 40% think that they maybe do. Liberal views are frequently discussed in the classroom, in the form of poking fun at Trump or criticizing Republican policy. It appears to often be instigated by students, but usually supported by professors, as one registered independent student shared: “It is not uncommon for professors to make jokes about how Donald Trump is a bad candidate. This is frequently prompted by jokes made by students.” It’s important to note this trend of politics in the classroom does not exclude Republican viewpoints; a few students in the survey wrote about how their economic professors present more conservative viewpoints when discussing Reaganomics in class.

We can ask ourselves two questions now. Is it inevitable that political biases seep into the classroom discussions? Secondly, what balance must be achieved between fostering a dialogue of intellectual debate and creating a welcoming environment for all?

Some students argue that these political viewpoints are unavoidable, because everyone has their own political biases. As one student notes: “I think it’s impossible not to. With so many classes that focus on activism, social justice, and the like, the emphasis is on causes that fall under the traditionally ‘liberal’ agenda that not everyone may agree with.” Indeed, is it even possible to skirt around politics when teaching a class on activism or economics? Eventually, you reach a point where you have to share your own opinion.

So it’s hard to avoid bringing your political views into the classroom. However, people can definitely try to avoid at least openly declaring your political support — but some professors choose not to, even sharing whom they’re supporting in the presidential election.

Most people would agree that dissension encourages debate, which in turn can sprout new and better ideas. A homogenous society where everyone agrees is very boring — can you imagine watching a presidential debate where each candidate just said, Yep, I agree exactly with what she said? That doesn’t make for very good television, or encourage the development of new ideas. We want the same environment on campus — a place where people can disagree and then learn from each other. A politically correct campus where teachers and students feel unable to share their viewpoints in fear of insulting students would not be conducive to the highly charged intellectualism of Stanford. We came to Stanford to learn and to have our views challenged.

But can that really happen if students feel so polarized that they can’t even share their viewpoints?

Many Republicans feel that they’ll be stereotyped if they admit to being conservative. One student wrote that “it’s an unspoken rule that if you’re a Republican, especially in this election, you’re seen as a privileged bigot with backwards views.” Ouch.

So what does that mean then? In a classroom, are students supposed to swallow their views and pretend to agree with the norm? In Stanford’s effort to broaden all of our horizons, is silence something we want to encourage in the potential world leaders emerging from our classrooms?

And it’s not only Republicans who fear their peers’ judgement. One liberal-leaning student claimed that despite agreeing with most of the liberal philosophy propagated on campus, his pro-Israel views caused him to feel “ostracized from the [liberal] community that is supposed to care” for him (which will rename unnamed for the sake of anonymity).

Some students fear losing the respect of their classmates and their teachers if they share their political views. One Republican student anonymously responded: “There is an underlying sentiment that all Republicans are insane and racist. If I were to say something conservative it would literally ruin relationships with my fellow classmates.”

Of course, some of you might read this and think — Well, of course that’s not true! I would not judge a fellow classmate because of their political views. However, that someone feels this way indicates that some students don’t feel that this campus has an environment that welcomes their opinions. And that means that they won’t share their ideas in class, especially if they fear a figure of authority may belittle them.

Of course, it varies from teacher to teacher; some remain devotedly unbiased while others feel comfortable sharing their views. I don’t pretend to know what the correct balance is. We aren’t in high school anymore, where teachers had to remain devotedly bipartisan or risk angry phone calls from parents. But what I know for certain is this: We are creating a climate in which some students feel unable to share their political views, and if we believe that diversity of thought is integral to a flourishing intellectual community at Stanford, we need to figure out a solution so that all students can be open about their opinions without fearing rejection.

Contact Caroline Dunn at cwdunn98 ‘at’ stanford.edu.