Jeff Smith ’89, the founder of a company called Smule, analyzes national musical tastes to predict a win for Hillary Clinton with 276 electoral votes.

Smith received a Ph.D. at Stanford’s Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) in 2013. In 2008, he founded Smule, a company specializing in applications that focus on the social aspects of making music. Along with Mark Dunning, Vice President of Data & Analytics at Smule, Smith has been using data from the company’s millions of users to measure the ideologies of swing states in the upcoming election.

The Daily spoke with Smith and Dunning about their research in electoral trends, music and cultural indexes.

The Stanford Daily (TSD): What are the electoral trends that you have been studying?

Jeff Smith (JS): It’s an exciting time because if you look at the history of our study of music and ethnomusicology, there’s been a dearth of data. It’s a fascinating time to be able to look at massive data sources. … and begin to draw inferences… across the domain of music and even adjacent domains such as the election. We’re not claiming to be the Gallup poll. … But what we can do, which is perhaps [even more interesting], is tell you how the country is divided along cultural lines.

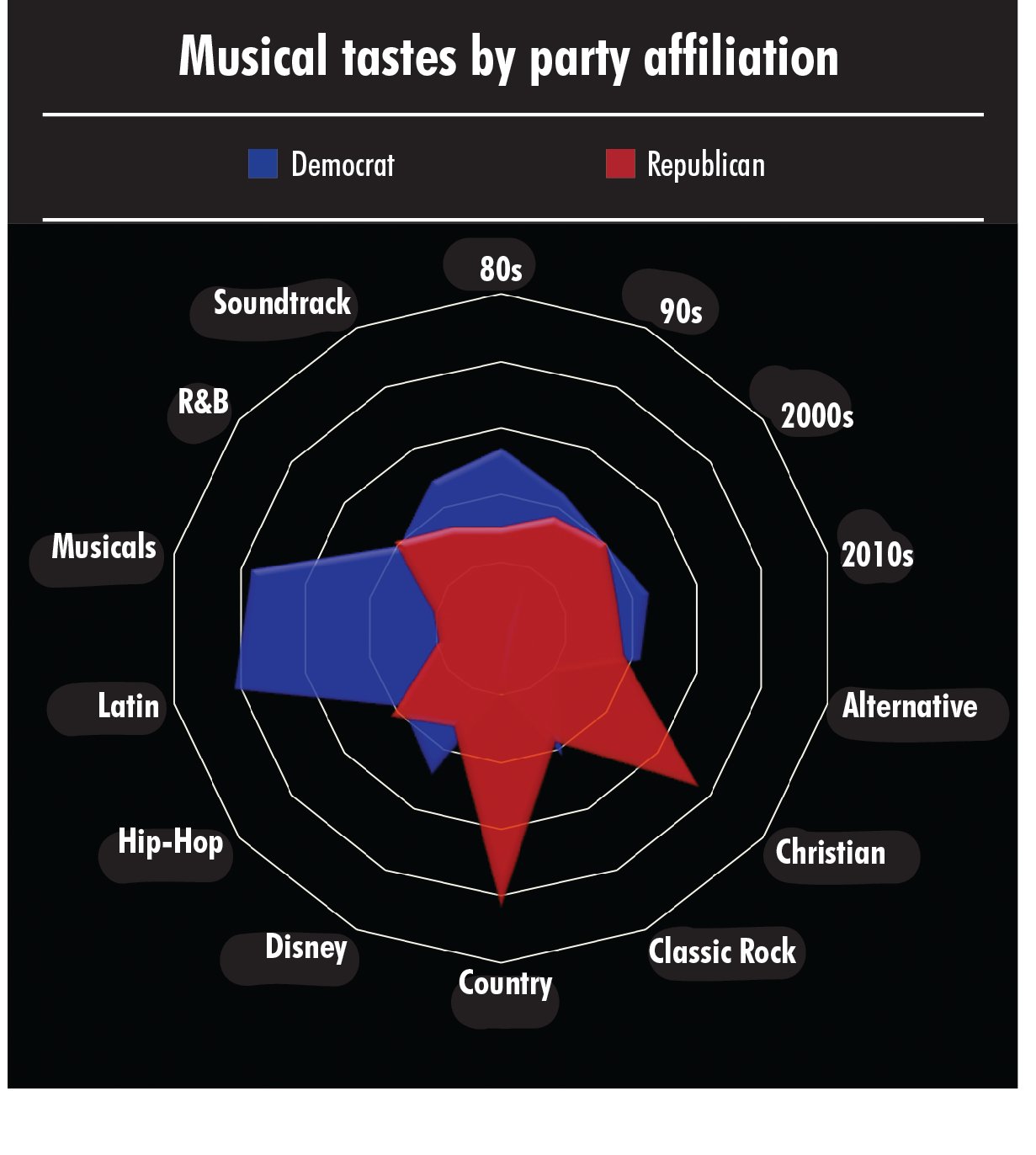

For this study, we looked back and picked 100 million performances of people singing songs through their mobile phones in the United States, organized by their state. We noticed that there was normative behavior in some of the core red and blue states in terms of musical preference.

Specifically, in the blue states, there is a stronger preference for musicals and Latin music. In contrast, in red states, there is a stronger preference towards country music and Christian gospel music. Also, in the blue states there is a surprisingly strong preference towards music from the 80s and early 90s. … We’re not calling your political preference, but [rather] how the country lines up culturally, as manifested in music.

TSD: Can we go through a specific example of this trend?

Mark Dunning (MD): We know that people in Ohio tended to sing country songs. We also noticed, juxtaposed to that, they also had a very strong preference to singing punk songs. … This type of contrast is what we tend to see within the undecided states. … We also know that there is a strong preference for 80s and 90s music, and we noticed this within several of the undecided states.

JS: In the end, [the preference for 80s and 90s music] tilted a state like Ohio just marginally blue. … For the record, when we put out this analysis a week and a half ago, we had a very different election in terms of the polling. We thought it would be pretty close in terms of the electoral vote, and people were saying, “There’s no way it will be that close,” and yet here we are.

TSD: Why did you choose to apply music to analyze culture during this election?

JS: First and foremost, we’re not so interested in the election, per se, as far as our business goes. … But, I’d say we are more interested in why people across the world have different forms of musical preferences and what we can do with our products to motivate deeper engagement to music.

The broader objective is the scale of the impact of art and music across a global community. … We were motivated to see if we could find the closeness in the election manifest in the cultural preferences for music, and what we found is “yes.” What the data showed us is that, in fact, there is a significant cultural divide in the country, and against that backdrop, the election makes a lot of sense.

TSD: Do you think that music is a better cultural predictor than other characteristics of the population? Why?

JS: I think if you want to understand a culture, you have to listen to its music. … I think music is intrinsic to who we are, and that’s why I’m so excited about this new field that Stanford is pioneering. … Jonathan Berger up at CCRMA is the lead on this work. We now finally have the data and the tools to begin to understand the relationship of music to culture and from that better understand our world, and why people engage, or not, in the arts. If we really want to understand who we are as a people, [then] I think music is fundamental to developing that, more so than a political poll.

TSD: Would you say that music merely demonstrates ideology, or is there an extent to which music informs and creates beliefs?

JS: I think it cuts both ways. … Of course, [beliefs] develop over time. It’s influenced by immigration, technology, by all sorts of trends. It gives us some pause to think about what we’re doing. Are we preserving culture? Are we destroying culture? Are we creating new culture? Maybe, in the end, we collectively are creating new culture in terms of how music is shared across diverse places and people.

This transcript has been condensed and lightly edited.

Contact Nic Fort at nfort ’at’ stanford.edu.