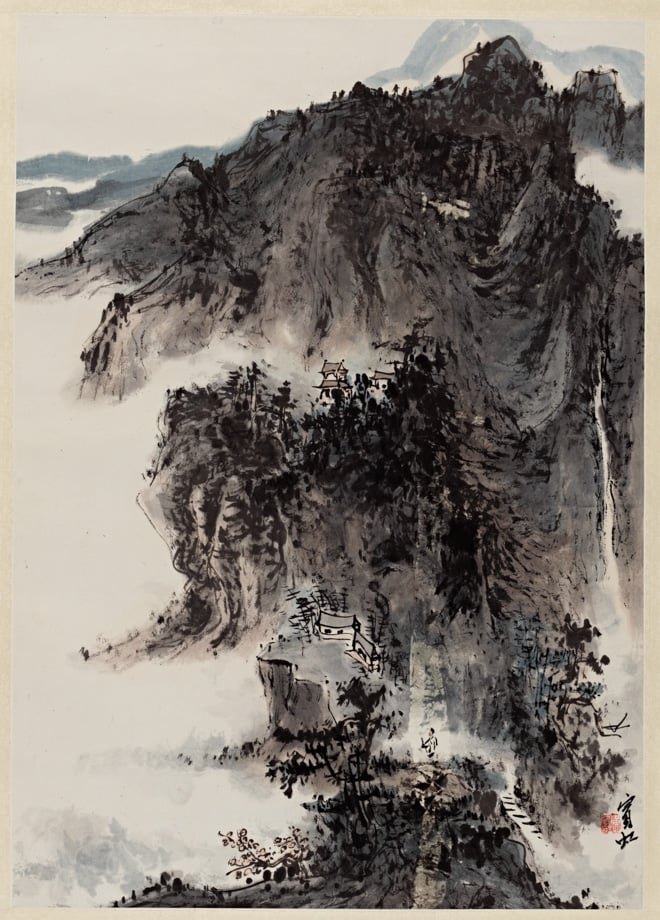

Huang Binhong (China, 1864–1955), Mountain Landscape, c. 1953. Ink and color on paper. Gift of Dr. Shirley Sun (A.B., 1964; A.M., 1969; Ph.D, 1974), 1994.113

The Cantor Arts Center is currently featuring a series of exhibitions entitled “Object Lessons: Art & Its Histories,” which is organized around foundational art history courses at Stanford. The exhibits seek to transform the gallery space into a hub for academic discussion and critical thinking about visual art and its cultural contexts.

“Object Lessons,” as they appear in the Madeleine H. Russell Gallery, focus on modern Chinese art from the late 19th century to the present day. These works — or objects — generally manifest themselves as a series of paper wall scrolls, emblazoned with ink renditions of traditional Chinese landscapes. Richard Vinograd, Christensen Fund professor in Asian art, selected the works to complement the undergraduate course “From Shanghai Modern to Global Contemporary: Frontiers of Modern Chinese Art.”

“Object Lessons” is clean and minimalistic in its presentation. The walls of the space are plain and free of clutter, drawing full attention to the soft, intricate textures of the scrolls that hang from the walls, equidistant from one another.

The wall scrolls on display are notable for their verticality and the sense of vertical motion they convey, despite the static scenes they depict. Ink strokes spiral upwards to form cliff faces and bamboo shoots in Zhang Daqian’s “Bamboo, Orchids, and Chrysanthemums.” In a 1946 landscape painting, Huang Binhong uses negative space to suggest a winding river that twists and turns its way upward across the surface of the scroll.

Feng Zikai’s “Only the Mirror Knows the Beauty of a Poor Girl” is one of the most delightfully unique pieces on display in “Object Lessons.” Zikai’s roots as a cartoonist are evident in the piece’s meticulously inked lines and pastel colors — a departure from the loose and monochromatic ink strokes of Zikai’s contemporaries. A vignette depicting a lone woman gazing stolidly into a mirror, “Only the Mirror Knows the Beauty of a Poor Girl” is simultaneously playful and sobering (as cartoons tend to be).

A staple of landscape paintings across history is a small, solitary figure situated in the landscape. The presence of the figure imbues the landscape with a sense of sprawling scale and suggests a sort of storyline. Zheng Wuchang’s “Leaning on a Tree and Listening to the Waterfall” places a figure at the base of a waterfall, perched under the branches of a gnarled mass of trees. The breathtaking scale of the piece, coupled with the lone figure, conveys a sense of adventure or the beginning of a perilous journey.

“Finding representation within abstraction” seems to be an apt characterization of the Chinese brush painters’ style. Chinese brush painting has roots in calligraphy and employs many of the same tools and ideologies. In particular, Chinese painters seek to convey meaning through few, purposeful strokes of the brush. This is perhaps best represented by Fu Yiyao’s 1979 landscape painting of a series of towering cliffs. Viewed from up close, the painting melts into loose and indistinguishable ink stains and brush strokes, and the cliff faces seem to hold traces of Yiyao’s hand and energy.

Contact Eric Huang at eyhuang ‘at’ stanford.edu.