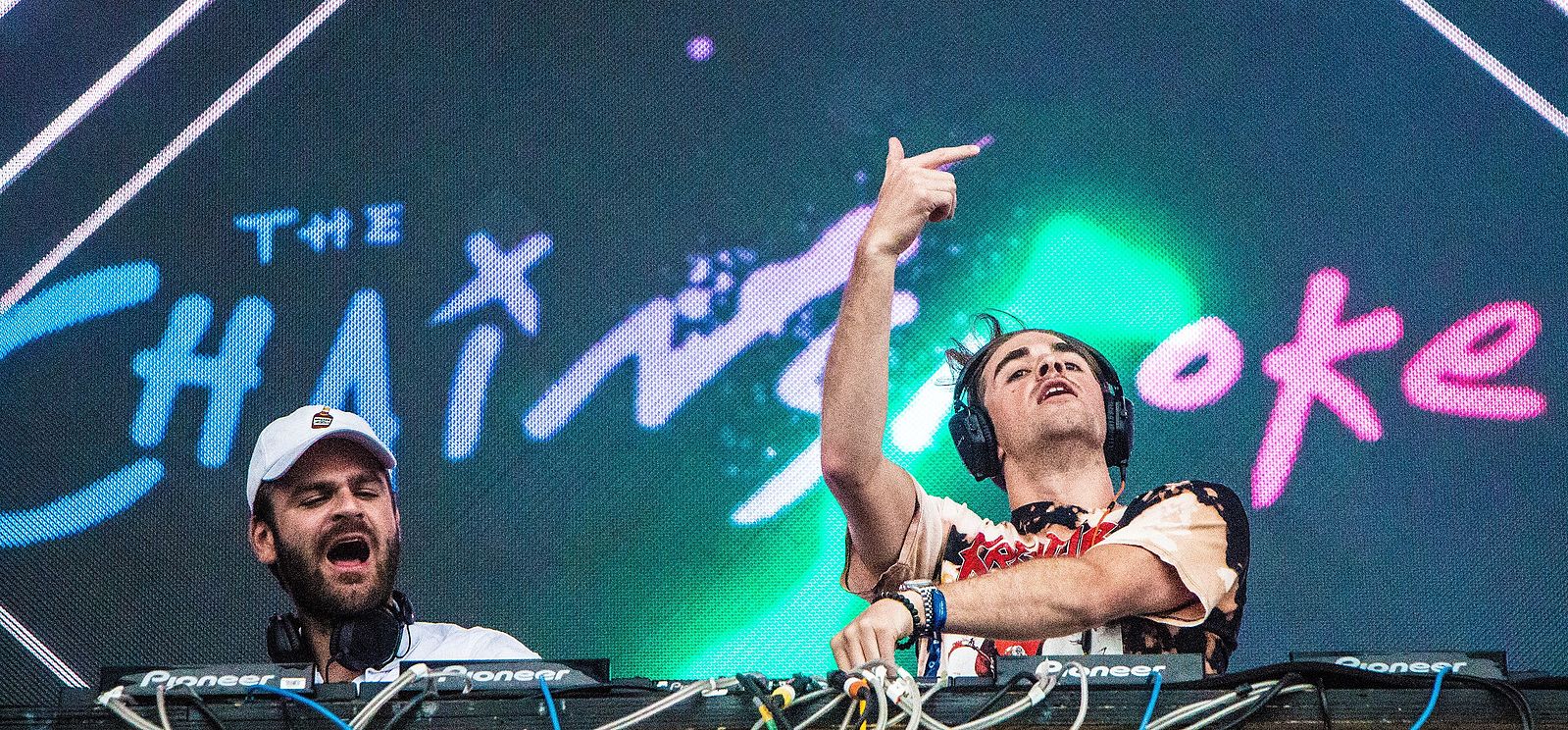

On Jan. 30, Esquire Magazine culture writer Matt Miller set the world of Electronic Dance Music (EDM) ablaze when he called The Chainsmokers the “Nickelback of EDM.” The story, shared 33,000 times the day after it broke, was quickly picked up by major EDM outlets from Your EDM to EDM Sauce. In the article, Miller lambasted The Chainsmokers for using bankable cliches that have come to define EDM: generic musical tropes, shameless sexism and phony sentimentalism. Miller is hardly unique: Deadmau5 has likened their music to “cancer” on his Twitter feed. Indeed, The Chainsmokers are guilty as charged, proffering the world a vapid brand of hungover, singalong, earworm pop that gets old after the first play — yet still elicits cheers on the hundredth. Their persona represents one of the most cliché and hated stereotypes of modern EDM: “We’re just frat boy dudes, you know what I mean? Loving ladies and stuff.”

No frat party is complete without at least three plays of “Closer.” But Miller expends a lot of effort scapegoating The Chainsmokers themselves for the downfall of EDM. It is too easy to condemn The Chainsmokers for being sexist and adhering to a money-making, hit-song formula. The music industry is inherently a money-making machine; it thrives on proven formulae of success and profit. This line of reasoning is often used to characterize pop as a musical race to the bottom. But if The Chainsmokers are to be crucified by the media for their — in Miller’s word — “lowest-common-denominator” sound, then we must condemn all artists who ever evolved their sound into something more “marketable.” Where are the diatribes against Dim Mak Records, a bastion of poppy, “frat bro” EDM, The Chainsmokers’s musical homestead? Where are our criticisms of the sexism and exploitation internalized within our music industry? Why must The Chainsmokers bear the brunt of the criticism for these deeper, older faults?

In the early years of the decade, when EDM was just beginning to gain mainstream popularity, many fans bemoaned a similar downfall of EDM. A phenomenon known as “big room house,” epitomized by Martin Garrix’s hit track “Animals” and other reverb-filled, spacey tracks saturated the sets at EDM festival mainstages. Big room house was ridiculed for being formulaic: Its simple structure of buildup-plus-drop ad nauseam combined with generic, ravey drops made it the Friday Frat Bro soundtrack of the 2010s. A YouTube video playing four big room house tracks simultaneously, poking fun at the ubiquitous homogeneity of the genre, went viral in the EDM community. This era of EDM was also characterized by rampant objectification of women — not much unlike the present state of EDM ruled by The Chainsmokers. Many proclaimed the death of EDM in that moment, but it has persevered and evolved into its present form in the face of impending creative doom.

Pop culture does not exist in a vacuum. Though pop culture is a modern invention, everything that is mainstream today was once part of the cultural margins, and EDM is certainly no exception. Pop music is often criticized as vapid today, but ironically, it assimilates an eclectic mix of threads from all genres of music and repackages the most iconic aspects of each into a slog of catchy, marketable clichés that our ears somehow can’t shake. So is it the artist that sells out, then, or is it the culture?

Take Zedd, for example, who reached mainstream success with his track “Clarity.” He has since taken on a more pop-style brand of EDM as well, defined by tracks like “Stay the Night” or “I Want You To Know.” Some say that his sound “matured,” while others still will fault him for “selling out.” They ask,“Where is the old Zedd?” But it is far too simplistic to assume that the musician is static. The musician is always in a state of evolution, developing new sounds and styles with each breath of musicality. But we pay no attention to that and focus our minds on disparate pieces of music from which we construct our musical conception of these artists. Zedd is hardly alone — the explosion of EDM has brought other artists like Calvin Harris, Avicii and Skrillex to the forefront of the commercial spotlight, and they too have garnered more than their fair share of admirers — and detractors. Such is the price of fame: No matter where they go, the haters follow, and they hate, hate, hate.

I am curious. I would like to know what these critics of pop culture artists want from the objects of their criticism. The Chainsmokers, in an interview with Billboard, insisted that they were not making music just to score hits — they had a particular artistic vision in mind. If that vision happens to conform to the pop industry standard, then who are we to fault them in particular? While The Chainsmokers are certainly problematic, utilizing sexist rhetoric in many of their songs and interviews, to ask them to renounce their current musical ways and become bastions of musical creativity is like asking a fish to climb a tree. It is nonsensical; it is not their musical raison d’être. Do fault The Chainsmokers for their shortcomings, but remember that the culture they inhabit is just as guilty. EDM is today a white male-dominated field, and if we are to innovate a new commercial future for EDM, we ought not to forget that.

At the end of the day, music is music. Complaints about mainstream music are hardly a new phenomenon, and the moment that The Chainsmokers reached mainstream acclaim with the arguably cringe-inducing “#Selfie” and mellow “Roses,” a large red target was painted on their backs. I will admit that I have no love for The Chainsmokers, but the problems they embody in the EDM industry — creative bankruptcy and rampant misogyny — are hardly their creations. These problems were part of marketable music long before they appeared on the scene — and the critic’s blame game is hardly a productive solution to the diseases of mass-market music. Amidst all the fuss, I would like to imagine that The Chainsmokers — and Nickelback — are watching over the hubbub, laughing their way to the bank.

Contact Trenton Chang at tchang97 ‘at’ stanford.edu.