The Stuart Davis exhibition, “In Full Swing,” does anything but.

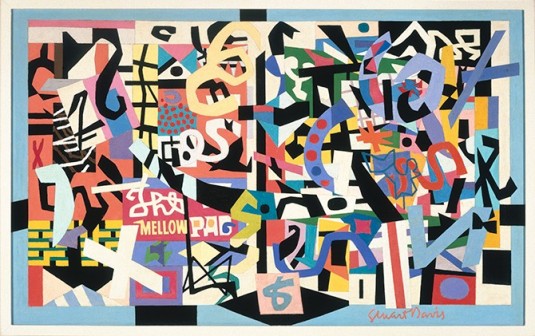

It’s a retrospective (up until August 6 at the de Young) of a virtuoso painter, known for his jamming of chic European modernism (Cubism, the Matisse fascination with color) and new innovations of America (jazz, cinema, the Model T). The exhibition covers an incredible range of sides to this not-boring city slicker — proto-Pop Art still-lifes of commercial goods, small-scale landscapes of Paris and Massachusetts, sprawlingly urban murals (with a hint of Marxism), all-over even paintings, and finally (the formula he finds for Masterpiece Art), nicely colored puzzle-pieces clashing with quasi-jazzy “spontaneity.” Depending on the way you look at him, Davis is either cool or cowardly. To combat incoherence, his spontaneity is exactingly worked out, before brush has hit the canvas. The payoff is immediate, running parallel to the brisk chill (not bad) of all his Dada-ish collages and post-Matisse/proto-Techicolor palates.

Judging from the one-note humor of his canvases (a comic panel — how lowbrow! — is the front page photo of his “Lucky Strike 1924” newspaper — how cheeky!), Davis never seems to have been plagued with gnawing personal angst. To him, Abstraction, hedonism and private pleasure (which he instantly rejected) were rascally diversions to the real purpose of art. To Davis, Art is best in an Apollonian (calm, controlled, even) state. His works craft a mutt mix that, like it or not, is American in its ambition and hit-or-miss in the landing.

The earliest paintings of “In Full Swing” show that, in his hunt for elusive American-ness, Davis happened upon an idea of it fairly quickly, never really expanding it to any radical extreme. He lived and breathed the 20th century and had his finger on the pulse of what made the new age so speedy. With “Edison Mazda” (a tongue-in-cheek still life of a blue lightbulb), the only hints of vibrancy are the active brush swipes near the crocheted mat; otherwise, it’s a painting representative of the Davis aesthetic: illusionistic, movie-like, give ‘em a virtual representation of the thing but never the thing itself. “Salt Shaker,” one of the huge successes, hums with subtle vibrations. The “Salt Shaker” lines’ uniform individuality (the ideal of American rhetoric) is festered with a jazzy energy that the later works completely lack.

Starting around 1928, Davis takes up a Paul Whiteman/George Gershwin approach to art, prettifying and domesticating the ugly city while latching on, floatie-style, to the jaggedness of city jazz. Prime example: In his “New York Mural” (1932), the sources (Mexican muralists, “Rhapsody in Blue,” Art Deco) come all spat out in a diluted state. “New York Mural” traces back to Davis’ inferiority complex (common amongst most Americans), which says that America — land of the coarse and vulgar — has to aim for “refinement” and “juxtaposition” with European gilt culture to achieve sweet satisfaction. The assumption is a good one in theory, but in practice, Davis leans too close to slavish Europeanism (see: the pretentiously-titled “Colonial Cubism”).

Rather than embracing a scruffy “lowbrow,” Davis goes for gilt. Thus, we get virtual illusions like his Parisian city works of the late 1920s. These postcard-ready landscapes are stuck in time by an anti-motion enamel coating, which sparkles like wolf’s teeth after a round of Colgate and Odol — a hint of mint which dissipates after about an hour. “American Painting” is just as frozen, despite its bold appropriation of a Duke Ellington lyric: “It don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got swing.” (And apparently, the reverse is true.) This sweet jazz is a hodgepodge of forms, all rigidity, fixed into position, découpage free of any signs of last-minute life.

Nearby, however, “Tropes de Teens” complicates my image, since it has an exciting half-awareness of its virtuality; this even further ossified remix of “American Painting” seems to presage Pop Art’s obsession with itself, its glorious repetitions.

Davis wows when he’s half-finished and not thinking in any direction, and for no audience but himself. In certain mid-period works (“Ultra-Marine,” 1943), Davis predicts the revolutionary, evenly applied, equalizing all-overness of Jackson Pollock. We get lost in the pinball-machine beauty of interlocking blocks interrupted by syncopated green dots. Elsewhere, “Landscape, Gloucester” (1922/1954/1957), despite being as irritatingly overworked as everything else, is much richer because the lines (as in “Salt Shaker”) are not exactingly rigid — the overall work denied the chance to become bogged down by perfection. The wet black and Jacques Demy red of “The Paris Bit” (1959) and the self-contained rhythms of “Salt Shaker” are cut from the same cloth.

Probably his saddest and most touching work are the Odol pictures, two still-lifes of mouthwash, tragically stuck in the past. Maybe in the 1920s, the viewer would have known the function of Odol. Today, however, we only see the wide gulf of a time foregone. The past-ness is, like chipping paint, an accidental byproduct of Davis’ work — yet no less compelling. The slogan (“it purifies!”) gives me no hint on what it even does. Something approaching Surrealism creeps in. The known-today-forgotten-tomorrow quality of advertising is far more apparent than in Davis’ obvious satire of the same subject in the 1950s, just a few steps beyond. The ’50s ad-blitz pictures aren’t half as interesting as the Odol gawking at itself in the mirror, in a weirdly stirring way.

Contact Carlos Valladares at cvall96 ‘at’ stanford.edu.