Huckleberry friends and buddy-boys: two great ones screen at the Stanford Theatre this weekend.

“Breakfast at Tiffany’s” plays Friday through Sunday, May 19-21, at 7:30 p.m., with a 3:10 p.m. matinee on Saturday and Sunday. Billy Wilder’s “The Apartment” plays on all three days at 5:15 and 9:35 p.m. (I’ll talk about this — my favorite romantic comedy — in Friday’s paper.) Both, of course, will show on 35 mm film.

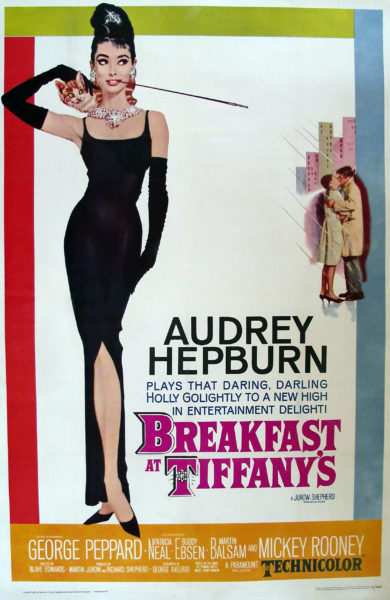

Based on the 1958 novella by Truman Capote and directed by Blake Edwards, “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” features, for better and worse, the most iconic and memorable Audrey Hepburn performance. “When you think of Audrey Hepburn, you think of ‘Breakfast at Tiffany’s’” – a phrase uttered with delight by producer Richard Shepherd and with exasperation by critic Karina Longworth. I sympathize with both takes. That image of Hepburn, cradling a cat on her shoulder (eccentric, offbeat) with her ridiculously long cigarette-holder and her de Givenchy black dress (chic, perfect), is the elegant, sumptuous, pop-art shorthand of not only Holly Golightly, but also Audrey Hepburn, and the film itself. But, in so many ways, it’s a reductive shorthand; the actual Holly of the film (and the actual Audrey Hepburn) is far more sorrowful, complex and angst-ridden than the happy-go-lucky kook of the poster implies.

The Holly Golightly of the Hollywood “Breakfast” is the result of several authors: the writer Truman Capote, the star Audrey Hepburn, the director Blake Edwards and the composer Henry Mancini. Let’s start with Capote first. Holly, as imagined by Capote, was an attempt to reckon with perhaps the most important woman in Capote’s life: his mother. Peter Krämer suggests that Capote based Holly on his mother, Nina, who, like Holly Golightly, grew up in the rural South, came to New York looking for a life of glamor and bon-bons, changed her name from “country-ish” to “city slickin'” (Lillie Mae to Nina, Lulamae to Holly), married in her late teens and left her Southern husband for a sophisticated Latin American (a businessman in Nina’s case, a Brazilian aristocrat in Holly’s). Nina, who was never a stable presence in Capote’s life and basically left him orphaned, eventually committed suicide in 1954; “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” would be the next substantial work Truman would write. Holly ended up a compendium of his mother and the several high-society New York female friends he associated with in the 1940s and early ’50s. The openly gay Capote was deeply interested in the women who try to re-make themselves in a big city, “spin in the sun for a moment like May flies and then disappear.”

Capote famously said he envisioned Marilyn Monroe for the part of Holly. Confronted about his thoughts on Hepburn in a 1968 Playboy interview, Capote didn’t mince words: “[My] book was really rather bitter, and Holly Golightly was real — a tough character, not an Audrey Hepburn type at all. The film became a mawkish valentine to New York City and Holly and, as a result, was thin and pretty, whereas it should have been rich and ugly.” But we shouldn’t take Capote’s word for it, since if we look long and hard, the ugliness of Holly and her world are there. It takes Audrey Hepburn and Blake Edwards to bring it out in classic Hollywood terms.

What has kept “Breakfast” in the American pop canon for half a century is not its false lovey-dovey vibe, but its “falseness” in and of itself — a common theme among Audrey Hepburn’s most famous films. “Breakfast” is just one of a series of Hepburn vehicles (along with “Roman Holiday,” “Funny Face,” “My Fair Lady” and Billy Wilder’s lesser-but-crucial “Sabrina”) centered around the Cinderella-like makeover (or reverse de-mystification) of Hepburn — a process which reveals how a woman’s image is mediated by bourgeois mores and strict tastes. Whether the outcomes are triumphant (“Sabrina,” “Funny Face”), tragic (“Roman Holiday”) or ambiguous (“My Fair Lady”), Hepburn’s films all question the perception of her characters’ individuality by the people (usually well-to-do men) surrounding her. Voyeurism of the woman is encouraged: “Sabrina” and “Funny Face” are less interesting on the narrative level than on that of the costume; they’re all about how Hepburn trades in her poor kids’ dresses for Parisian haut couture. At some point, the Hepburn character breaks the monotony: In “Roman Holiday,” she goes from robotic smiles and rote beauty queen answers to (in a slapstick scene that would make Blake Edwards jealous) smashing goons with guitars, winking at cats and throwing life-rafts to drowning villains. Later, in “My Fair Lady,” Hepburn’s Eliza proudly rejects the misogynistic haughtiness of Professor Henry Higgins (Rex Harrison). By the final scenes (when Eliza has become a lady [woke?]), she simply sits at the sidelines, hocking spit-balls to discourage Higgins’ pomposity, until he suddenly realizes (“damn, damn, damn, damn, damn”) that she can live without him, but that he can’t live without her.

Audrey’s always being judged, looked at, measured to impossibly high standards — which perhaps mirrored how she felt before she hit it big with “Roman Holiday” in 1953. In her excellent podcast “You Must Remember This,” Karina Longworth talks up the dark past that contributed to Hepburn’s gangly body look — a story even more traumatizing than Holly Golightly’s. While she was training to be a world-class ballerina, World War II broke out, Britain declared war on Germany and Hepburn’s family relocated to Netherlands in 1939, thinking it would be safe there than in England. But just a year later, in 1940, the Nazis occupied part of the Netherlands; Audrey’s uncle was shot and killed for his involvement with the Dutch resistance, and her half-brother Ian was deported to a German work camp. She said: “Had we known that we were going to be occupied for five years, we might have all shot ourselves. We thought it might be over next week … six months … next year. That’s how we got through.” Audrey survived the infamous Dutch famine of 1944 when the Nazis cut off access to rations for citizens in German-occupied Holland. She ate only endives, tulip bulbs and water, confined in bed, reading for days on end, in order to keep her mind off hunger. But the repercussions were life-lasting. She contracted asthma, jaundice, anemia and edema from malnutrition. At the end of the war, she weighed 88 pounds. Since her weight and weakened body prevented her from becoming the prima ballerina she so wanted to be, she took up acting instead. Even on stage and on screen, she had to fight off the insults against her gangly, “awkward” body frame from gossips and film critics who were oblivious to the incredible challenges of her early life — just as all the men in “Breakfast” are convinced that Holly is nothing more than kook and cotton-candy on the surface. They see her solely in their fairytale projection of creeping male desire. Holly and Audrey are more — much more.

Nothing is ever known in Audrey Hepburn’s world — or Blake Edwards’s. Edwards’ role in the movie is rarely foreground, and that’s probably for good reason. Even the sharp Edwards scholar Sam Wasson doesn’t include “Breakfast” as one of Blake’s masterpieces. Maybe that’s for good reason. “Breakfast” isn’t really “a Blake Edwards film.” If anything, it’s Hepburn’s show; the sophisticated physical gags and manic vulgarity that makes up Edwards’ brutally personal masterworks (“The Pink Panther,” “A Shot in the Dark,” “Days of Wine and Roses,” “The Great Race,” “What Did You Do in the War, Daddy?”, “The Party,” “S.O.B.,” and “Victor/Victoria”) don’t show up in “Breakfast.” But the Edwards touch is writ most large at Holly’s cocktail party — the film’s greatest setpiece, a Jacques Tati-like swarm of beehive hair-jewels-bodies, which Pauline Kael wrote “ranks with the best screen parties of the era.” Here, the wacky irreverence and psychological horror of parties is pungently rendered. Amid the funky gags which keep toppling on top of one another include a token Asian woman (she’s an unexpected extra, especially if you’re aware of the film’s other Asian…) who drifts around and looks lost in the sea of white; a drunk woman who thunders to the ground like a chopped tree (“TIMBER!” yells Holly); a lady’s pillbox-hat is caught on fire by Holly’s cigarette holder and quickly extinguished with a glass of whiskey; and a dinner-guest who laughs hysterically, then breaks down in mascara-black tears at her own image in the mirror, unable to recognize herself. Edwards’s brand of dark, vulgar comedy (which may be even wilder than Wilder) was always good at deflating the absurd cartoon-personas we construct for ourselves when we schmooze in social settings. It’s when he’s making fun of these outward projections of ourselves that he arrives at his odd pathos.

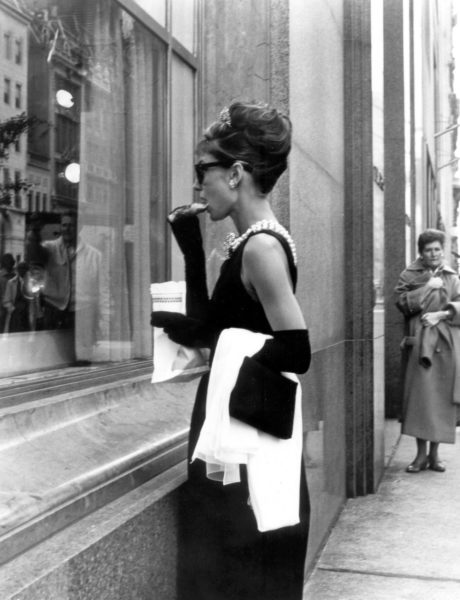

Edwards’ manboy-ish obsession with slapstick and acidic bodily satire (cf., the infamous glow-in-the-dark-condoms scene in 1989’s “Skin Deep”) has tended to draw attention away from his films’ vivid female protagonists: the gender-fluid Julie Andrews in “Victor/Victoria” and “Darling Lili,” Lee Remick’s tortured alcoholic in “Days of Wine and Roses” and Hepburn here. It’s Edwards who pushes the reading of Holly as a transparent, ghostly presence whom no one, not even the male authors Capote and Edwards, will ever fully know. In Edwards’ famous first shot, Holly departs a taxi on a surreally-empty Broadway, dressed in a lavish black dress and sunglasses at 5 a.m., approaches a Tiffany’s window, and gawks at her reflection. So many questions. What’s she thinking? Who does she see? Is she going somewhere? Is the Lulamae of years past still there? Do her eyes conceal happiness? Or play up her misery? All these questions flit by Hepburn’s bony face. All remain unanswered by the film’s end, which (framed in a rainy, tight alleyway which threatens to swallow Hepburn and Peppard whole) is Edwards’ way of undercutting the sappy Hollywood-mandated ending. Does it work? Not quite. But is the overall emotion happiness? Not quite.

Edwards has been rightly criticized for his frequent (lack of) taste, which lapsed more frequently than that churlish imp Billy Wilder. Case in point: Mr. Yunioshi, Holly’s Japanese cartoon of a neighbor, played by the grating Mickey Rooney. Rooney’s cataclysmically-unfunny mugging, pathetic racism and poorly-timed slapstick — encouraged by Edwards — only appears in four short scenes, each less than a minute long; but the stupidity of each appearance ensures Rooney sticks in the mind far longer than he should be allowed to. In Capote’s novella, Yunioshi is actually a respectable Japanese photographer and freelance artist. But except for a slurred line, you wouldn’t get that from Rooney’s Yunioshi, who curls his upper-lip, bares his front teeth and plays up the white man’s idea of har-har Orientalism. Pretty much no one on set found it funny except Rooney and Edwards; everyone ended up denouncing it, with Edwards ending up being the most apologetic, chocking it up to an egregious lapse of judgment.

(For a potential sign of maturation on Edwards’ part, check out Peter Sellers as the Indian actor in “The Party,” Edwards’ 1968 avant-garde Hollywood comedy. Among the many weirdnesses of this artistic triumph — the apotheosis of Edwards’ 1960s comedies — is Sellers’ brownface performance, which doesn’t play up the aggressively racist Indian stereotypes that Sellers employed on comedy records and TV appearances of the 1950s. Instead, Edwards directs Sellers to underact, resulting in a weird naturalism which hews closer to the universality of Chaplin’s Tramp or Tati’s Mr. Hulot. The result may be the most soulful character that either Edwards or Sellers created.)

Hepburn’s Holly is a stand-in for those of us who have felt insecure and shallow on the inside, who have projected outward an illusion of who we’d like to be — but ultimately aren’t. She suppresses her Texas past life because she doesn’t think it can ever square with her NYC bohemianism. But when she starts to raspily sing Henry Mancini’s folksy, country-potato tune “Moon River” (an Oscar-winning song), she proves that, yes, the two lines can meet. Henry Mancini, in a 1970s newspaper interview, on the matter:

“It’s unique for a composer to really be inspired by a person, a face or a personality, but Audrey Hepburn certainly inspires me. If you listen to my songs, you can almost tell who inspired them because they all have Audrey’s quality of wistfulness — a kind of slight sadness. To this day, no one has [sung] it with more feeling or understanding.”

The ending has Holly finding (temporary) happiness. But this is a Hollywood movie, where things happen ten times faster (and prettier) than in real life. Holly, a hipster-loner, waits dreamily for romance to pick her life up — but for most of Blake Edwards’s film, it’s an aching wait. In the meantime, the men in Holly’s life cast down harsh, brutal judgments on her. A movie executive (Martin Balsam, one of late Hollywood’s great character actors) pegs her as “a real phony — a great kid, but a phony.” A suave Brazilian aristocrat in line to be the next president of sugarcane country says she’s “dangerous for any man’s image.” And our lead guy, a formless WASP pudding (nicely under-played by George Peppard), calls Holly “a coward” and tells her straight up, “You’ve got no guts.” The criticisms only seem to ennoble the featherweight Holly; like the glamorous new actresses of the French New Wave contemporary to Hepburn’s time (Jeanne Moreau in Jacques Demy’s “Bay of Angels,” whose ending is a close cousin to “Breakfast at Tiffany’s”), Hepburn/Holly look at a steady romance like it was a gambler’s game, an unsure but exciting roll of the dice.

It’s tempting to read Holly Golightly as some ’60s prototype of the manic pixie dream girl — but that’s an exasperatingly modern reaction to a character who cannot be troped in a box. The best thing about Holly is that she is a wonderfully wicked iceberg who only elects to show the tip. Not even Capote’s narrator could tap into Holly’s interior. We can only gauge what she isn’t, and where she may go. This dizzying mystery — the self-mysteries we all keep — is enough to guarantee Holly her place in the pantheon of great American pop figures.

Contact Carlos Valladares at cvall96 ‘at’ stanford.edu.