It’s Admit Weekend. Campus has never looked more alive – White Plaza bustles with opportunity in every direction, pamphlets fly between hands and every office opens its doors in eager welcome to the newcomers. To prospective freshmen wandering hopelessly amidst the chaos, Stanford exists as a symbol of new hope and tangible success: the American dream finally realized. The University presents itself as a generous lending hand, lush with resources ready to embrace students from all walks of life and on every level of the socioeconomic spectrum.

Stanford’s admissions website boasts a $22.4 billion endowment to “[provide] an enduring source of financial support for fulfillment of the university’s mission of teaching, learning, and research.” Elsewhere, the words “DIVERSITY” and “OUTREACH” jump off the page.

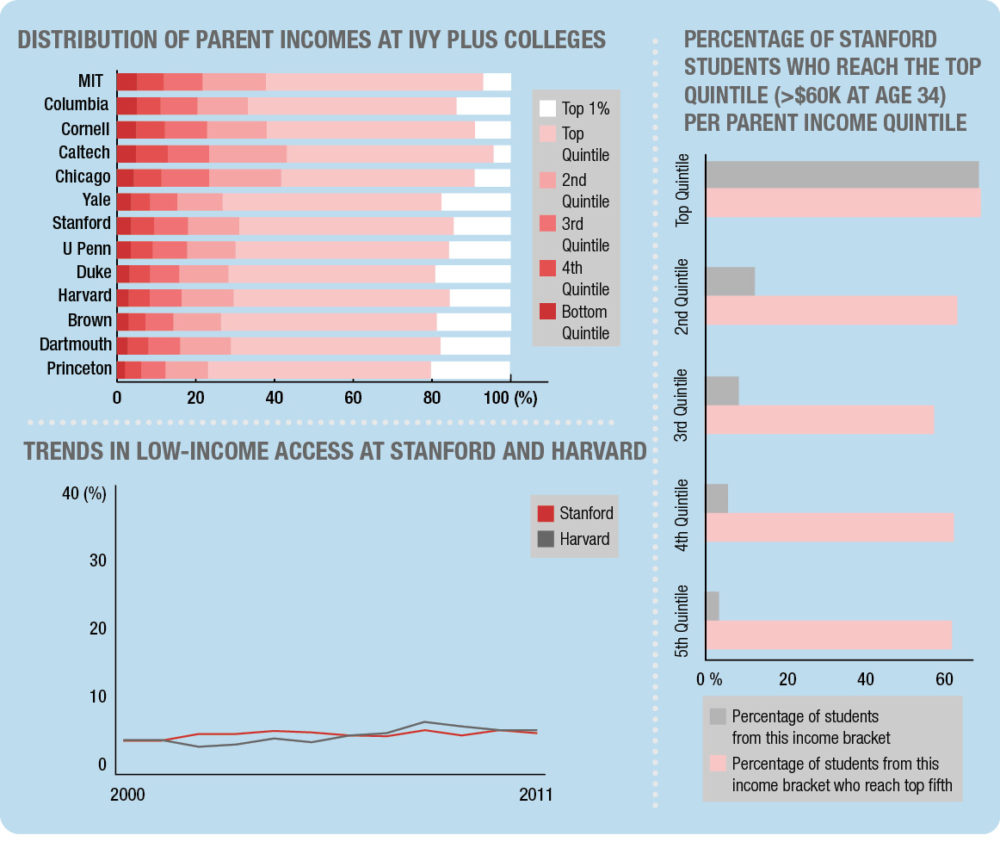

However, recently released data from studies by economics professor Raj Chetty and his colleagues stands to challenge this rosy image. Their research shows that at 38 colleges in America, including five Ivy League schools, the number of students whose parents belong to the top 1 percent of the income distribution surpasses the number whose parents fall within the entire bottom 60 percent. In other words, more students come from households with incomes exceeding $630,000 per year than come from households earning below $65,000.

At Stanford, the numbers are not much better: As of 2013, more students come from the top 1 percent than the bottom 50 percent of the income scale. This statistic is true for the so-called Ivy-Plus colleges in general, which include the eight Ivy League schools as well as Stanford, University of Chicago, MIT and Duke.

Amid a host of efforts to make Stanford more socioeconomically inclusive, why does the University’s student body remain so dramatically skewed toward the rich? Despite the expansion of financial aid in recent years, as well as reports of increases in students represented in the lower income quartiles, the lines tracing change in Stanford’s socioeconomic makeup remain remarkably flat. Ultimately, these trends have major implications for promoting social and economic mobility.

The data

The Equality of Opportunity Project – pioneered by Chetty and colleagues from Brown University, UC Berkeley and the U.S. Treasury – is a collection of studies using big data to understand the relationships between educational opportunity and social mobility. Together, these researchers linked anonymized tax returns to the attendance records of over 30 million college students at nearly every college in the U.S. between 1999 and 2013. They then used this administrative data to develop publicly available “mobility report cards” that provide statistics correlating students’ earnings in their early thirties to their parents’ incomes for each college.

The results Chetty and his collaborators found — recently publicized in a widely-read article in The New York Times — were striking. The data calls into question the role that institutions of higher education play in fostering both upward income mobility and interaction between students from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds.

“Only 3.8% of students come from the bottom 20% of the income distribution at Ivy-Plus Colleges,” the study states. “As a result, children from families in the top 1% are 77 times more likely to attend an Ivy-Plus college compared to children from families in the bottom 20%.”

Across all colleges, this trend of income segregation parallels the income segregation across neighborhoods in the typical U.S. city.

Robert Fluegge, a predoctoral research fellow involved with Chetty’s work at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR), said he was shocked when he first saw the numbers on college socioeconomic diversity.

“It’s not just Stanford,” he said. “I think it’s valuable to put numbers on problems like this because it galvanizes people; it gives them a starting point to get something done about it.”

Despite the initial income gap between students from high- and low-income backgrounds, Chetty’s research found that students from these backgrounds have remarkably similar earnings outcomes at any given college. So it’s not a mere matter of preparedness, as it seems low-income students are more than capable of filling any initial achievement gaps between them and their higher-income peers: The barriers that prevent low-income students from attending elite universities are more complex.

In the United States as a whole, a strong inequality of future earnings persists between students of different backgrounds: Children from high-income families tend to land 30 percentiles higher in the income distribution than peers from the lowest-income families in adulthood. But research indicates that when considering the student pool from any given elite college, this gap shortens to only 7.2 percentiles, a figure 76 percent smaller than is seen nationally.

This trend holds true at Stanford as well. Despite large disparities in the number of students from the highest and lowest quartiles of the income scale, there is little difference among income outcomes.

Chetty’s research also makes a distinction between universities that foster upper-tail mobility, which sends students to the top 1 percent of the earning distribution, and normal mobility, which sends students to the top 20 percent. Mid-tier public schools with high access to low-income students, such as the City University of New York, offer the highest normal mobility rates – much higher than that of Ivy-Plus colleges like Stanford.

Schools that accomplish the highest rates of upper-tail mobility, on the other hand, are generally elite Ivy-Plus colleges with minimal access to low-income students.

“We definitely don’t want to tell Stanford or other institutions what to do, but we think our data suggest [elite schools] could be doing more to admit more poor students,” Fluegge said. “We can’t say that for certain without the admissions data, but the things that we’ve seen … suggest that students at Stanford that are low-income tend to do basically as well as students that are high-income.”

Chetty and his colleagues’ work also reveals that, while the number of low-income students attending college rose quickly during the 2000s, the number of students from bottom-quintile families at four-year colleges and selective schools did not experience significant change. Stanford’s percentage of bottom-quintile families was more or less stagnant at below 5 percent throughout the first decade of the 2000s.

Given Chetty’s data, what’s to explain the lack of socioeconomic diversity among Stanford’s student body?

Barriers to diversity

One of the major problems Stanford faces in attracting low-income students is that outreach, while extensive, still struggles to connect competitive students with the University.

“Although we tried to increase financial aid, we also have to work very hard to get the message out to low-income students that those resources are available,” said Dereca Blackmon ’91, associate dean and director of Stanford’s Diversity and First-Gen (DGen) Office.

Dean Richard Shaw echoed her sentiment and noted that only 47 percent of Stanford students receive need-based financial aid.

“The reality is there are competitive kids out there from all walks of life, all backgrounds, that will be uber-competitive,” he said. “And in some cases, they don’t apply. … They just [don’t] realize they [can] look outside their own regions or neighborhoods.”

Indeed, there is research being done outside of Chetty’s group that explores why low-income, high-achieving students do not apply to selective colleges at the same rates as wealthier peers that are similarly high-achieving as measured by test scores.

Scott and Donya Bommer Professor in the School of Humanities and Sciences Caroline Hoxby, for example, has shown that these high-performing students tend to apply as though they were low-achieving, low-income students. This may be due in part to a lack of advising and college counseling resources at high schools in more low-income areas, Fluegge posited.

“There are a lot of things that are keeping students from applying … [whether or not there exists] emphasis on higher education … at your school: how many students from your school go to a [place] like Stanford versus going into the workforce or community college, whether you have mentorship from your teachers or counselors and how well they support you,” said Anakaren Cervantes ’17, a student staffer at the DGen Office who works in admissions as a diversity outreach associate. “If you don’t have that and you don’t have resources outside of school, then it’s a lot harder for you.”

Less access to resources may starkly influence low-income students’ understanding of which colleges are the best academic and financial choices. Interestingly enough, students from poor families often end up spending more to go to worse colleges, remarked Fluegge.

“[At] colleges like Stanford [and] Harvard … many of these students would be eligible for a full ride,” he said. “And that is not the case at the schools they tend to go to.”

Once at Stanford, though, low-income students face an additional set of challenges as they navigate financial aid and unanticipated expenses. As Angela Umeh ’19 noted, understanding how financial contributions and aid actually work can be a source of endless confusion and frustration.

“There was never a moment that someone came through and talked to me about my financial aid package,” Umeh said. “Stanford still makes you pay a student contribution… that I didn’t know I would owe. The financial aid office staff tries to be helpful, but… they don’t always have the solution to your problem, and at best they can delay the problem.”

Moreover, in a survey of the entire Class of 2016 conducted by the DGen Office, 50 percent of students who responded reported that they send money home. The Office continues to work with students to identify other potentially hidden financial obligations, such as ensuring food security during spring break, finding places to stay during winter break and summer and covering unanticipated medical expenses.

“Random expenses hit really hard,” Umeh added. “[I] accidentally booked the wrong tickets home, [but] school keeps going on.”

What’s being done

Ultimately, it is clear the University has a duty to help mitigate broader systemic issues at play in financial inequality, but the solution is by no means one-shot. And Stanford is working to increase the socioeconomic diversity of its campus.

According to Dean Shaw, the prospective Class of 2021 contains Stanford’s highest percentage of admissions offers to first-generation and low-income students to date. 2015 saw an expansion of the financial aid program: Parents with annual incomes below $125,000 are now expected to provide zero contribution toward tuition, and parents with incomes below $65,000 are expected to provide zero contribution toward tuition, room or board. Previously, those aid cutoffs were $100,000 and $60,000 respectively.

“I think financial aid has made a huge difference, and in fact, we’ve seen some nice increases in students represented in the lower income quartiles and particularly this year,” Shaw said, though he could not specify distributions.

However, some argue Stanford must do more to grow its financial aid. Unlike some peer schools such as Harvard and Princeton, Stanford still does not extend its need-blind admissions policy to international applicants. Shaw said that need-blind international admissions are “still very much on [Stanford’s] agenda” but that budgetary constraints following 2008’s economic downturn set it back as a priority.

With an endowment of over $20 billion, expanding need-blind admissions to all prospective students might seem a no-brainer. But according to Shaw, the necessary funds are still lacking. However, he said, Stanford has been increasing the amount of aid it gives students from abroad.

Need-blind policies aside, the latest increases in financial aid may not make much of an impact on students from the poorest families, who were likely already covered with near-full aid. To combat persistent underrepresentation of low-income students, Stanford will need to pursue other strategies.

Stanford recently joined the American Talent Initiative, a consortium of 68 universities with a commitment to expanding college access to 50,000 additional low-income students within the next decade. Every summer, Stanford invites and covers the cost of travel for 30 to 50 high school counselors from public high schools and community-based organizations in low-income communities to help them learn to advise their students to apply to places like Stanford. Last summer, the University also launched the Coalition Application, an alternate online college application established by a group of universities with a commitment to helping high school students acquire information and plan for application to selective colleges.

A number of initiatives are also in place to help low-income students overcome socioeconomic barriers once on campus: The Leland Scholars Program, for example, exists as a summer bridge program that allows students to get an academic head start by taking courses during the summer before their freshman year — as well as by exposing them to faculty members who seek to increase students’ sense of belonging at Stanford.

Meanwhile, at New Student Orientation, the DGen Office hosts luncheons and outreach events for parents and students to provide information about the resources and support systems provided at Stanford. During the school year, the University also provides a generous Opportunity Fund to help students overcome financial challenges such as paying to fix a broken computer or bicycle, traveling to attend conferences, buying textbooks and meeting unforeseen medical expenses. Furthermore, Student Financial Services hosts financial literacy workshops on campus to help first-generation and low-income students navigate loans, taxes and more.

Umeh applied to Stanford through the national QuestBridge program, said that Stanford’s participation in the initiative strikes her as a notable positive step towards including low-income students. QuestBridge links high-achieving, low-income high school students with elite schools through a matching system. Participants in the program include six Ivy League schools; Harvard is absent from the list.

In terms of her dorm experience, Umeh noted that accessing financial aid has never presented an issue and that the First Generation and/or Low Income Partnership (FLIP) program also provides useful alternatives to University programs, helping out with, for example, an emergency grant for a sudden flight home.

“As a whole institution compared to other elite schools, Stanford does do a pretty good job trying to help the low-income community and be aware,” Umeh said. “It’s definitely doing a lot, and I don’t want to disregard that — but on a personal level, you do notice where the gaps are, and talking about that can help Stanford be aware of it. … [I]t’s kind of hard when you’re getting so much money from a school to be like, ‘Actually, do you have more?’ You don’t want to be ungrateful, but honestly, sometimes you do need more resources — or at least recognition that it’s hard.”

A complex problem

The challenges faced by low-income students are more than just economic; they’re also psychological. Blackmon cited research by Associate Professor of Psychology Greg Walton describing the “stereotype threat” that exists for both low-income and high-income students, who feel at risk of personally fulfilling negative stereotypes about their broader groups.

“There is this image of [Stanford] in terms of being high-income that is intimidating for low-income and/or first-generation students,” she said. “Folks come in wondering [if] everything from where they buy their clothes to what they can afford to eat is going to impact their ability to have a sense of belonging here.”

In a social setting, income inequality can create stress for low-income students as they struggle to decide whether or not they can convey to their higher-income peers that they cannot afford certain luxuries such as eating out, joining organizations with fees or participating in extracurricular activities with high costs. Such stress extends into the classroom, too: For example, Blackmon cited an assignment in which a professor asked students to write about their last vacation.

“If you’re high income, then that’s something you often can readily think about, whereas if you’re low-income, it might not be,” she said.

She said professors sometimes make outright assumptions about whether or not their students relate to being low-income, though a significant percentage of students do.

Umeh said that some professors make more of an effort than others to provide cheap textbook options, but she added that it’s difficult to predict how sensitive professors will be towards low-income students’ circumstances.

“Professors can go either way – some are more aware than others,” Umeh said. “You never know if you can tell a professor, ‘I can’t afford this.’”

Still, she stressed that that students from high-earning families ought not to receive stigma for the way they grew up.

From pre-admission through their time at the University, students ask themselves, “Will I be able to afford Stanford?” And “afford,” these days, is a loaded word – not just for Stanford. There is a sociological, psychological, socioeconomically untenable cost to the effects of an institutional setting in which such striking economic disparity exists within the student body.

“Income mobility for low-income [college] students is parallel to [that of] middle-income and high-income students,” Blackmon said. “[They are all] equally likely to end up in the top 1 percent. Is Stanford’s primary objective to make students high-income? No. But if we’re going to challenge economic disparity, don’t they have to have the economic mobility to do that?”

Undeniably, institutions of higher education are important engines for economic mobility. And while the goals of the University are certainly broader than fattening the wallets of its students in the future, the greater challenge remains: What is the University’s obligation to affect inequality within itself, and what does it still owe to its students in this regard?

Contact Claire Wang at clwang32 ‘at’ stanford.edu.