This past year, Stanford’s athletics teams made heavy use of SyncThink’s EYE-SYNC technology, which employs virtual reality headgear to diagnose concussions and provide quantitative data on a subject’s eye-tracking abilities within 60 seconds. On June 26th, SyncThink released the second version of EYE-SYNC, which expands the scope of its eye-tracking analysis while continuing to diagnose concussions in under a minute.

This is remarkably fast, and it allows coaches and sports medicine professionals on the sidelines to immediately determine whether it’s safe for an athlete return to the game after an injury.

The company’s founder is Dr. Jamshid Ghajar, who is also a clinical professor of neurosurgery at Stanford University Medical Center and the director of its Concussion and Brain Performance Center, which he founded in 2014.

In a SyncThink press release, the company describes that the updated, FDA-approved device improves on last year’s version by not only testing for eye tracking impairment (difficulty in following a moving target when a person is still) but also vestibular balance dysfunction.

“Vestibular balance is all about orientation,” said Ghajar. “It’s measuring how well you’re orienting when you move in relationship to the outside world.”

Both eye tracking and vestibular balance problems are signs of a subject’s disorientation and can be major indications of a concussion. However, the already difficult task of concussion diagnosis is made even more difficult by the ambiguity surrounding the word “concussion.”

“As far as diagnosing a concussion, no one knows what a concussion is,” he said. “The public thinks that we all know what it is, but there’s no accepted diagnostic criteria.”

To help solve this, Ghajar is working with the military to define concussions, and he has identified 5 subtypes of severe symptoms. In addition to eye tracking and vestibular balance issues, the list includes migraines, cognitive fatigue and anxiety/depression.

EYE-SYNC in use

Stanford’s sports teams have helped test EYE-SYNC the past two seasons. Every Stanford athlete has gone through the test so that each of them has baseline measurements to use in the future when assessing their condition.

Stanford’s concussion protocol, which it submits to the NCAA every year, requires using EYE-SYNC as a first line of concussion diagnosis for Stanford’s varsity athletes.

Stanford has an aggressive policy when it comes to helping concussed athletes recover. They’re put on cardio exercise machines to restore sleep cycles, which allows them to recover in three to four days.

In addition to its use at Stanford, EYE-SYNC is being adopted by other universities, despite not yet being used by professional sports leagues.

“I think their [professional sports’] posture is, ‘let’s get a lot of colleges using it first and then we’ll go pro,’” he said.

Ghajar believes that EYE-SYNC can be used not only for concussion diagnosis but also for measuring athletic performance and preventing injuries. For example, if an athlete didn’t sleep the night before and thus demonstrates poor eye tracking abilities, he or she can be taken out of the game to prevent poor performance or a potential accident.

The portability of EYE-SYNC means that it can be used anywhere – even on the battlefield. The U.S Army has ordered multiple EYE-SYNC units, and they are currently testing the device with troops in Afghanistan. In fact, the Department of Defense provided over 30 million dollars to SyncThink in 2013 to fund clinical trials and the development of EYE-SYNC.

The science behind EYE-SYNC

Virtual reality goggles like Samsung’s Gear VR currently don’t come with eye-tracking hardware. Therefore, SyncThink relies on German eye-tracking company SensoMotoric Instruments (recently acquired by Apple) to build the necessary hardware into the Gear VR.

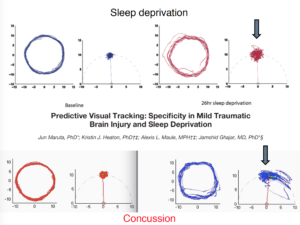

This allows EYE-SYNC to test for ocular-motor impairment by having subjects wearing the headgear follow a point of light that travels clockwise in a circle. The target goes around the circle for 15 seconds, twice, and within the next 30 seconds, EYE-SYNC reports data on how accurately the eyes follow the target.

During the test the eyes of subjects who have a concussion jump suddenly ahead to where the target will be.

According to Ghajar this is because the brain operates by predicting the future.

“So if your brain wants to go 60 miles per hour, the way it works, it will press all the way down on the gas and go 120 miles per hour, and use the brake as a fine control to go 60 miles per hour,” he said. “That’s why the brain weighs 2% of the body but uses 20% of the energy.”

The “brakes” that Ghajar mentioned are a metaphor for the brain’s capacity of inhibitory control. Concussion patients suffer from a lack of inhibitory control, which can explain why their eyes jump forward rather than following the target.

With EYE-SYNC’s latest release, trainers can also make subjects wearing the headgear move their head around while trying to keep their eyes focused on a fixed point. This tests for vestibular balance dysfunction and makes the overall concussion diagnosis even more comprehensive.

How EYE-SYNC is different

Concussions began to appear more in the news in 2006, as soldiers in the Iraq War suffered various forms of traumatic brain injury. Back then, a person was only diagnosed with a concussion if they lost consciousness.

Imaging technologies such as the MRI and CT scan have become increasingly popular, but when it comes to concussion diagnosis, they aren’t necessarily reliable. According to Ghajar, when performed on concussion patients, “90% of them are normal.”

Besides its speed and accuracy, what truly makes EYE-SYNC stand out among other on-field concussion tests is its ability to provide objective metrics. There’s no way to convince a medical professional or trainer that everything’s alright when EYE-SYNC produces quantitative data that indicates a concussion. Athletes often claim they’re fine despite being injured so they can re-enter the game. In scenarios such as these, there’s only one solution.

“Put on the headset,” says Ghajar. “You can’t fool that.”

Contact Deven Navani at deven.navani ‘at’ gmail.com