Using data collected from a smartphone app, Stanford researchers found Americans are widely distributed in terms of physical activity, a trend that correlates with high obesity levels. The study revealed that lower activity inequality can be achieved with more “walkable” environments.

“[When activity inequality is high,] the obesity levels are extremely high, [and] the gap between men and women is high,” said Jure Leskovec, lead researcher in the study.

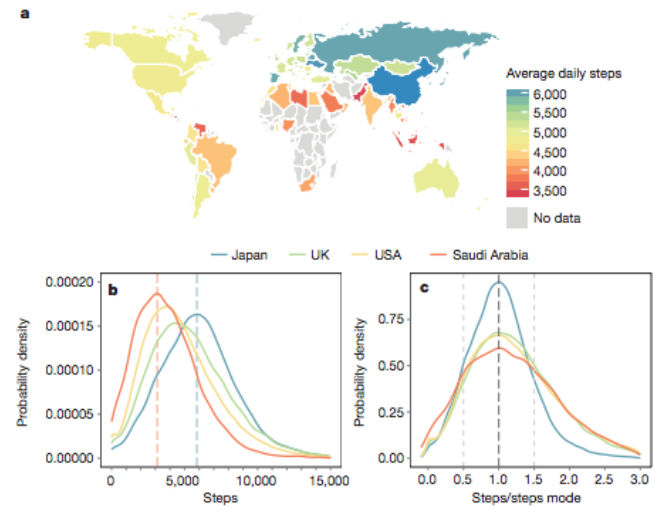

In collaboration with Azumio’s smartphone app Argus, the researchers not only studied the overall average steps taken by 717,000 individuals in 111 countries but what fraction of a country’s population got a certain amount of steps. This distribution curve revealed the U.S.’s high activity inequality, an indication of unhealthy trends.

A high inequality and wide distribution means that there is a large gap between those that are active and those that are sedentary. Countries with this quality will experience high levels of obesity. The study revealed that low activity inequality indicates not only less deviation in the number of steps taken, but also typically more average steps for the population as a whole.

The researchers designated 69 big cities with a walkability score, which factors in how pedestrian-friendly a city is. The walking routes to nearby amenities, population density and block lengths within a city all contribute to the its score.

For instance, the suburbs of Arlington, TX, may be more car-dependent than the cityscape in San Francisco, CA and will have a lower walkability score. San Francisco’s high score indicates less inequality and a narrow distribution curve, meaning most individuals get similar, high amounts of activity.

According to Mobilize Lab data science director Jennifer Hicks M.S. ’06 Ph.D. ’10, more walkable environments will likely boost the physical activity level of women, who currently walk much less than men in the U.S., and close the activity gap.

“When a city is more walkable, it doesn’t seem to be the case that the already active people are more active,” Hicks said. “It seems to benefit everyone.”

Changing the environment would also have more long-term effects than fitness app or device usage, according to the paper’s first author Tim Althoff, who is a Ph.D. candidate in computer science. The researchers are interested in actively encouraging smartphone users in hopes they adopt healthy, long-term habits through reminders and social networks.

“It’s not an individual problem,” Althoff said. “It is more like a societal problem — about how we can create and design environments, our neighborhoods, our cities in a way that allows us to be more active.”

Contact Renee Hoh at renee.hoh ‘at’ gmail.com