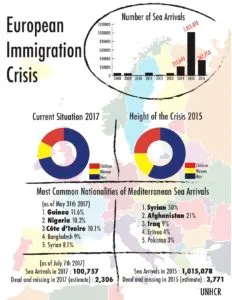

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) since the start of 2014, 1.7 million people, the equivalent of 34 packed Stanford stadiums, have immigrated into Europe by crossing the Mediterranean Sea. Though the journey is potentially deadly and doesn’t guarantee a life of comfort on the other side, many are desperate enough to try. According to the UNHCR, in 2015 alone 1,015,078 came into Europe via sea travel. Such large numbers spell out nothing less than a crisis.

A group of researchers, including Kirk Bansak M.S. ’17 Ph.D. ’18, Jens Hainmueller and Dominik Hangartner, at the Stanford Immigration Lab recently published results from a survey of over 18,000 citizens of 15 European countries asking participants about their beliefs on what the best system for allocating asylum seekers is. The surveys found that a majority of Europeans claim to be in favor of a proportional allocation system, which is based on “each country’s capacity over the status quo policy of allocation based on the country of first entry.”

The Immigration Policy Lab at Stanford is a group of researchers connected to a broad network of scholars in different departments and different universities. The lab works with NGOs and government agencies to evaluate immigration policies, with the goal of bettering the lives of immigrants and supporting the communities that take them in.

The immigration crisis not only consists of an extremely complex logistical challenge to relocate people, but also plays into national politics, puts into question democratic and humanitarian values and threatens the integrity of the European Union (EU). Though the number of immigrants has drastically decreased since 2015, the journey is far from over for most asylum seekers and migrants. Some of these immigrants have been nomads for years, causing the state of crisis to prevail and hence foster a desperate need for policy reforms.

“European voters of all different types – we are talking about people both on the left and the right, people young and old, people with more or less education, and European voters across all 15 countries that we surveyed–pretty generally all did seem to exhibit very strong humanitarian concerns of roughly the same magnitude,” Bansak said.

Going into the study, the researchers were confident that when people were told the number of additional asylum seekers their country would receive as a result of a proportional allocation system, their support for the system would decrease. Though they found that some support diminished, however, the majority support persevered.

“One thing that was surprising to my colleagues and [me] when we did our most recent study was the extent to which people actually care about the fairness and international responsibility,” Bansak said.

Currently according to the Dublin Regulation, a EU law originally established in 1990, the asylum system in Europe requires asylum seekers to submit their claim to asylum in the first European country they enter. This has put a lot of strain on bordering countries, most notably Greece and Italy.

“[The current policy] makes a lot of sense in historical context, but in a crisis that is just not a workable situation,” Bansak said.

There have been some early moves to change the current policy in an effort to resolve the refugee crisis that continues to present a huge issue in politics for the EU. In 2015, Germany and the Czech Republic both suspended the Dublin Regulation in order to process Syrian refugees.

“European countries have been thinking of reforming this system for quite a while” Bansak said. “But, one of things that is holding them back is policy makers [often seeking reelection] are really worried about public backlash.”

The survey’s findings also appear to oppose notions of anti-immigration views that some claimed was a key reason for the Brexit vote that led the United Kingdom to leave the EU last year.

“The Brexit vote may have reflected something that already existed in the UK’s public landscape, a certain hostility and antipathy towards immigrants among a large portion of the population,” Bansak said.

The public’s two strong opposing voices render it harder for policymakers to find a solution.

“It is a combination of a political communications challenge and a logistic challenge for European policy makers,” Bansak said. They have to respect the public’s will and balance a lot of strenuous demands on their societies, but it is also a crisis situation.

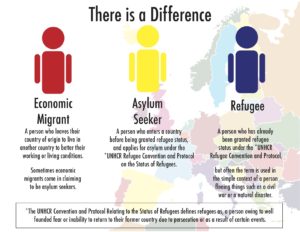

The public opinion is effected when it comes to different types of immigrants. In a previous study conducted by the same research group, they was found that people’s opinions on immigration differed depending on the type of immigrant, such as economic migrants (people who immigrate in search of better working and living conditions), asylum seekers (people who seek and apply for refugee status), and refugees (people granted this status often due to civil unrest or natural disaster in a previous country).

Officially, the UNHCR Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, defines refugees as a person owing to well founded fear or inability to return to their former country due to persecution or as a result of certain events. Under the UNHCR Refugee Convention and Protocol on the Status of Refugees, asylum seekers are granted the right to apply for refugee status which provides a critical layer of protection and support.

According to the earlier study, “Public preferences are also highly sensitive to humanitarian concerns about the deservingness and legitimacy of the asylum request, as well as the severity of the claimants’ vulnerabilities.” Moreover, the study found that “the public is opposed to admitting asylum-seekers whose principal motivation is to seek better economic opportunities and therefore might be regarded as economic migrants who do not meet the legal definition of refugee status according to the 1951 Refugee Convention.”

“The big thing that can lead to misconceptions is the distinction between different types of migrants,” Bansak said. “I think it is important to keep these distinctions in mind … because depending on whether you are thinking of something from a normative, from a legal, or from a purely practical dogmatic perspective, the answer could be very different depending on whether you are talking about an economic migrant, asylum seeker, or refugee.”

According to the World Economic Forum, migration and refugees is one of the six issues that will shape Europe in 2017. The widespread impacts the crisis has on European societies, politics, economics, and security has kept it at the forefront of European agenda.

Though the crisis may seem far away, in this interconnected world its geopolitical impact goes beyond the European capitals, due to the interconnectivity of markets, the spread of populist rhetoric, the example set by the policies, and the redefining of democratic and humanitarian responsibility.

Contact Diva-Oriane Marty at [email protected].