I’m not a huge fan of horror, so the following books are hopefully different from the “fright fest” Halloween recommendation lists that have been popping up online before Friday the 13th. Most of these books are dark variations of existing tropes or stories, seeking to unsettle rather than terrify the reader. They temper their grimness with a strange kind of optimism, which I think we could all use as we descend further into the dark nights of fall quarter. All of these books are also short and manageable during those odd hours between p-sets or papers.

1. “Every Heart a Doorway,” by Seanan McGuire

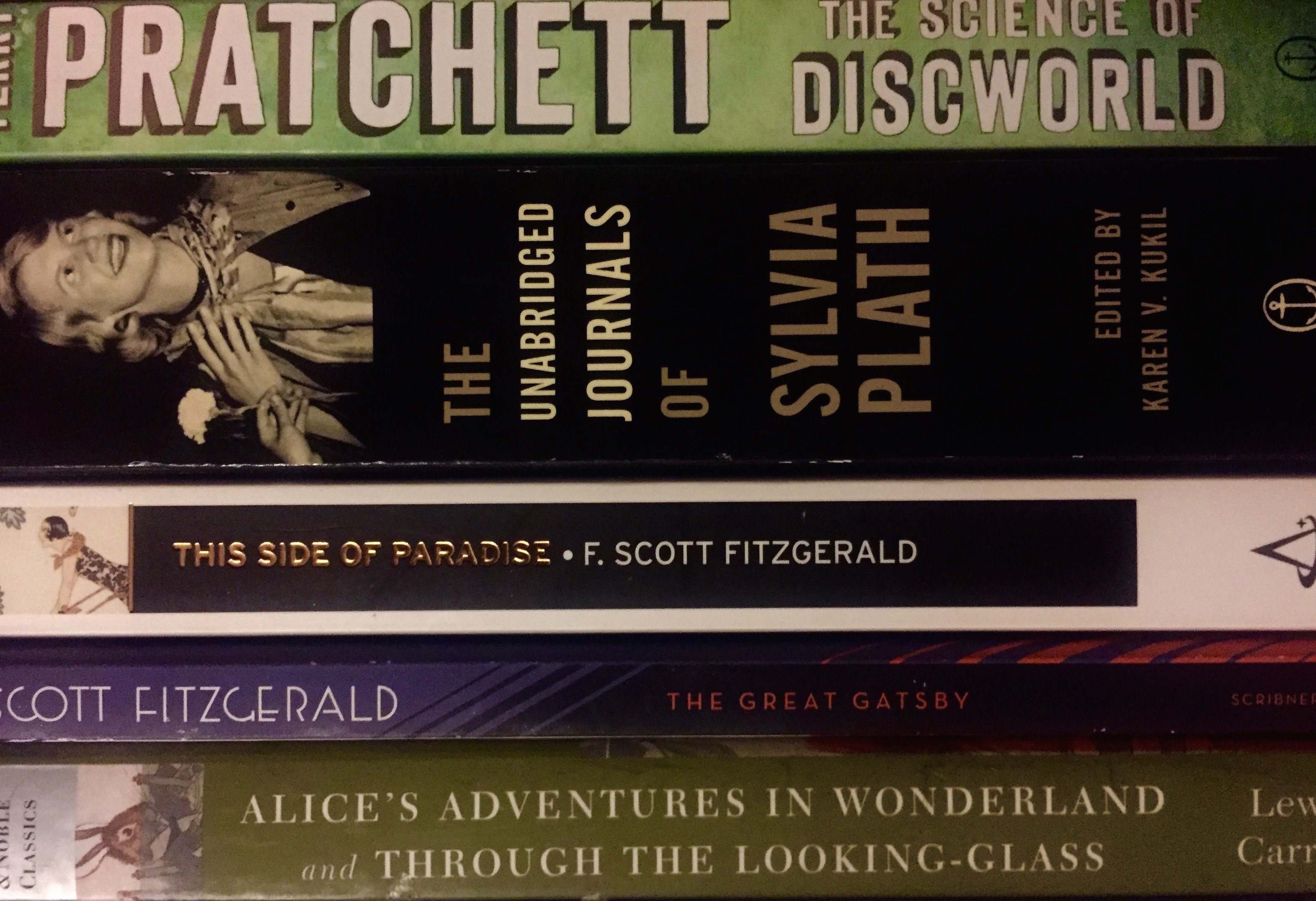

God, I love this book. While popular in the critical realm (“Every Heart a Doorway” recently won the 2017 Hugo, Alex and Locus Awards), McGuire remains a criminally underrated author in the popular consciousness. “Every Heart a Doorway” is the story of children who have to come to terms with being back in our world after fantastic adventures, like Alice returning to England after Wonderland or the Pevensies stumbling back out of the wardrobe. Whimsical yet matter-of-fact, McGuire’s tight, economic storytelling deftly explores a fascinating nexus of fantasy worlds. There’s some blood and death if you’re really into that, but it’s very no-nonsense. McGuire also very deliberately includes LGBTQ+ representation in her books, which is always a plus.

2. “Down Among the Sticks and Bones,” by Seanan McGuire

Technically a sequel and/or prequel to “Every Heart a Doorway,” “Down Among the Sticks and Bones” can easily be read as a standalone. Written in a much more fable-like tone than its predecessor — not least because the protagonists eventually adopt the monikers “Jack” and “Jill” — the novel revolves around a set of twins first introduced in “Every Heart a Doorway.” It chronicles their origin story in a world that is more Hitchcock film than Neverland, an eerie, colorless world known as “the Moors.” The novel poses — but doesn’t always answer — thematic questions about individuality, responsibility, agency and consequence, threaded through with omniscient third-person narration that gives the story the vibe of a moralistic Grimm fairy tale. Jack and Jill are complex, compelling characters, and the novel pits beauty and brutality against each other in both the literal and metaphorical sense.

3. “Trigger Warning,” by Neil Gaiman

There will definitely be more Neil Gaiman on this list, since horror-fantasy is essentially his name brand and I am a sucker for his work. One of Gaiman’s many short story collections, “Trigger Warning” is offbeat, earnest and deceptively sinister. Gaiman peppers each story with sharp wit, darkly entertaining plotlines and a surprising gentleness, upending readers’ expectations. The stories “My Last Landlady,” “The Thing About Cassandra” and “Feminine Endings” number among my personal favorites.

4. “Fire and Hemlock,” by Diana Wynne Jones

Perhaps best known for her novel (and the later Studio Ghibli adaptation) “Howl’s Moving Castle,” Diana Wynne Jones crafts a faerie cautionary tale in the tradition of “Tam Lin” and “Thomas the Rhymer” set in 1980s Britain. Jones combines classical mythological and narrative elements that contribute to the feelings of entrapment and adventure that Polly — the main character — experiences at the hands of ruthless old-school faeries. I recommend this book for fans of liminal spaces, medieval codes of conduct and moral ambiguity.

5. “Dark Places,” by Gillian Flynn

Most infamous for the psychological thriller “Gone Girl,” Gillian Flynn is a writer with a masterful understanding of pacing and plot development. Inspired by the trend of ritualistic Satanic crimes in the rural United States in the 1980s, Flynn’s novel “Dark Places” highlights protagonist Libby Day’s childhood survival of a massacre at the hands of her own brother. Flynn’s writing is unflinching and visceral, layering a plot that’s mesmerizing in a can’t-look-away-from-a-car-crash way. Perhaps the bloodiest book on this list, “Dark Places” is steeped in an intensely Gothic, aestheticized vision of the Midwest. Libby is at times off-putting in the same way that Netflix’s Jessica Jones can be — prickly, self-preservationist and take-no-shit.

6. “The Secret History,” by Donna Tartt

Tartt’s novel is one of the most engaging solitary works I’ve read in years. Serious and intellectual, the book hones in on college students at a New England liberal arts school and their Greek classes with an eccentric professor, after which the students become unhealthily obsessed with Bacchanal rituals. The narrator, Richard, is very much a Nick Carraway type; he’s the observer. As you slide deeper into the story, the characters slide deeper into messy situations with even messier answers – you’ll count at least two murders by the novel’s conclusion. Tartt asks the reader to consider the limits (or lack thereof) of human nature, the role of religion in society and the deep-seated need to belong.

7. “The Ocean at the End of the Lane,” by Neil Gaiman

I did say there would be more Gaiman titles on this list. While “Coraline” might be most people’s go-to Gaiman work on Halloween, “The Ocean at the End of the Lane” is an oft-overlooked novella of his that marries childhood whimsy with instinctual terror. Gaiman has repeatedly expressed the influence of such writers as Mary Shelley and C. S. Lewis on his stylized fairy tales, and this is hugely evident in the darkly imaginative “The Ocean at the End of the Lane,” a story about childhood fears targeted at fearful adults.

8. “Frankenstein,” by Mary Shelley

Since I recently reread this book for English 161, Shelley’s creation myth has been weighing heavily on my mind. Despite its ubiquity in pop culture, key themes of the novel have gotten lost in the translation between mediums; Shelley explores our responsibility to our own creations, whether morality is innate or learned and whether beauty is the same as goodness. “Frankenstein” weaves together the macabre and the heartfelt, giving us a lot less mad cackling on Frankenstein’s part and a lot more self-flagellating rumination.

Happy(ish) reading!

Contact Claire Francis at claire97 ‘at’ stanford.edu.