When you examine a typical stanza of poetry or admire the brushstrokes of a Rothko masterpiece, you can enjoy the full experience of condensed ideas made visible onto a page or canvas. But when fragments are missing, or whole sections are lost to the sands of time, what kind of experience are you really having with this artwork?

Despite the fact that we can, objectively, look at the same piece of art that others have seen centuries or millennia ago, we are not “seeing” the fullness of it with consideration of the sociopolitical context that formed the backdrop of the piece. We are fortunate to have recovered many ancient artifacts and artworks, but who knows if we are truly interpreting them correctly?

We are forced to consider this issue in many exalted works of art, such as the finest marble Greek statues that in turn have inspired Renaissance sculptors like Michelangelo. For many years people have admired the smooth marble planes of “Winged Nike” lacking adornment, only for art historians to later discover that these Greek statues were originally painted with garish bright colors to resemble their human counterparts.

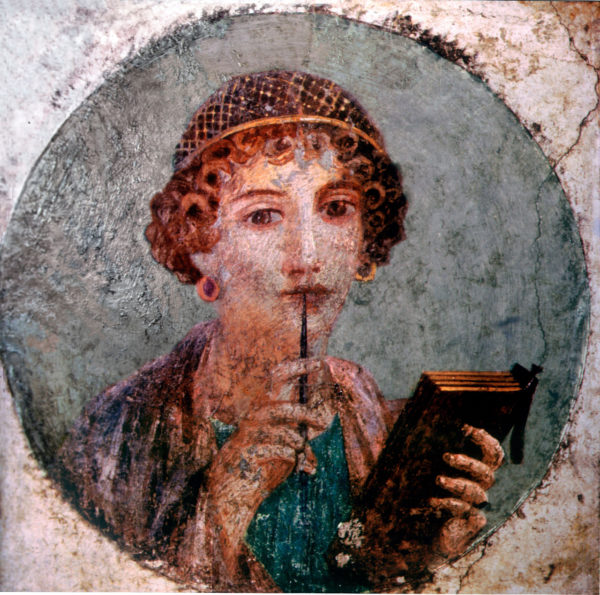

Such thoughts bring me to reflect on the Greek poetess Sappho from Lesbos, whose original nine collected books of poetry have only survived as one complete poem and hundreds of fragments. Particularly with the Anne Carson edition, readers have access to evocative phrases like “you burn me” or “far whiter than an egg,” but the translator leaves much space on the page to emphasize the emptiness of lost sections that may never be found.

Even now, Sappho and her works are shrouded in mystery — we are unsure of whether these poems were written for public and commemorative celebrations or for personal creation, if Sappho speaks for her own experiences or describes the budding love of another person, and even if Sappho’s family history is as accurate as historians have pieced together from other fragments of information.

But perhaps there is a new sort of beauty to be found in the chasms between words, even with the knowledge that some of the poet’s intent may be lost. Like the aforementioned Greek sculptures, though the paint, or the turns of phrases in the case of poetry, may have worn away, what remains still possesses its own ethereal grace. Our commitment to preserving history and the ruins of an ancient civilization can be its own study in its own form. (And as a side note, these disciplines are called archaeology and art history.)

After all, it is not as if artworks lacking in defined meaning have no place in modern society. Considering the surge in the late twentieth century for modern artwork, like Rothko’s “Orange and Yellow” or Kandinsky’s “Composition VIII,” even works that we have in their full capacity still leave viewers perplexed and uncertain of their meaning or the lack of one. Abstract art often forces the viewer to bring their own frame of reference and project their own ideas onto the canvas, a far cry from art from earlier eras, like Veronese’s Counter-Reformation “The Last Supper” which had the main idea of supporting the church. While the unique aspect of such abstract artworks, at least for my own viewing experience, is their ability to guide someone into a state of contemplation or pure emotion, I can sympathize with those who prefer a Michelangelo painting or a Rubens. The latter two are objectively much easier to interpret in the case of formal definitions of subject, style and the elements of art.

But with Sappho’s fragments or even marble Greek statues, we simply do not have access to their original forms. For all intents and purposes, unless an excavation were to suddenly reveal a stronghold of newfound ancient Greek artworks, these are all we have left to consider.

Now the question remains, is there enough for us to appreciate what is left behind?

In this way, perhaps one value of art is the ability for viewers to construct their own interpretation, whether it is for an abstract work that has no defined meaning or for the sake of filling in the spaces of a meaningful work with parts erased. Fragmented works of art from eons ago can certainly fit in quite well with this conceptual understanding, and Sappho’s love poetry from circa 600 B.C. becomes very relevant when considering the social movements of our current age.

And while I am saddened at the loss of so much of our human tradition passed down through arts and culture, I am hopeful that we can learn enough from these scraps to create more masterpieces — that can be faithfully preserved with modern technology — for our present era and future generations.

Contact Shana Hadi at shanaeh ‘at’ stanford.edu.