In my first month at Stanford, I’ve used my bike five times: once to go to CVS in Palo Alto, twice to go to the grocery store, once to go to a doctor’s appointment off campus and once to get to Wilbur on short notice. I have never biked to a class or meeting, and of the three times I’ve been to Trader Joe’s, I’ve only biked once. Normally, I walk.

This fact — that I own a bike but rarely use it on campus — baffles most of my friends. Why would you ever endure the trek over to the Graduate School of Business on foot? Isn’t that, well, a waste of time?

If walking had no purpose other than getting from point A to point B, then it would be a waste of time. But I do not walk to class simply to get from dorm to lecture hall. The walking itself, not the destination, is the reason why I walk whenever possible.

As Stanford students, finding time for ourselves to relax and reflect can seem impossible. When I’m with friends, I can’t turn into myself for calm and introspection. When I’m in my dorm room, I feel a constant itch to get something done, to finish a reading or get ahead on a paper due next week. I value meditation, yoga and mindfulness practices, but with all of my activities and academic demands, setting aside time to simply sit and relax has become a low-priority item on a constantly expanding checklist. With midterms and papers approaching, it can feel hard to justify a 30 — even 15 — minute break.

That’s where walking factors into my life. Walking is not empty, unproductive time; it gets me to my classes, the library, and my dorm. Nonetheless, it is not entirely a means to an end. Walking can function as a sort of meditation, a mindfulness practice to fit into the nooks and crannies of your day — fifteen minutes here, fifteen minutes there, and you’ve got an hour to relax and introspect.

Of course, it takes effort and practice to be mindful while walking. Walking meditation requires present-moment awareness and turning off the mental static that drives our stress response and anxiety. In order to turn walking into a spiritual practice, it’s important to notice both the world around you and the sensations of your own body.

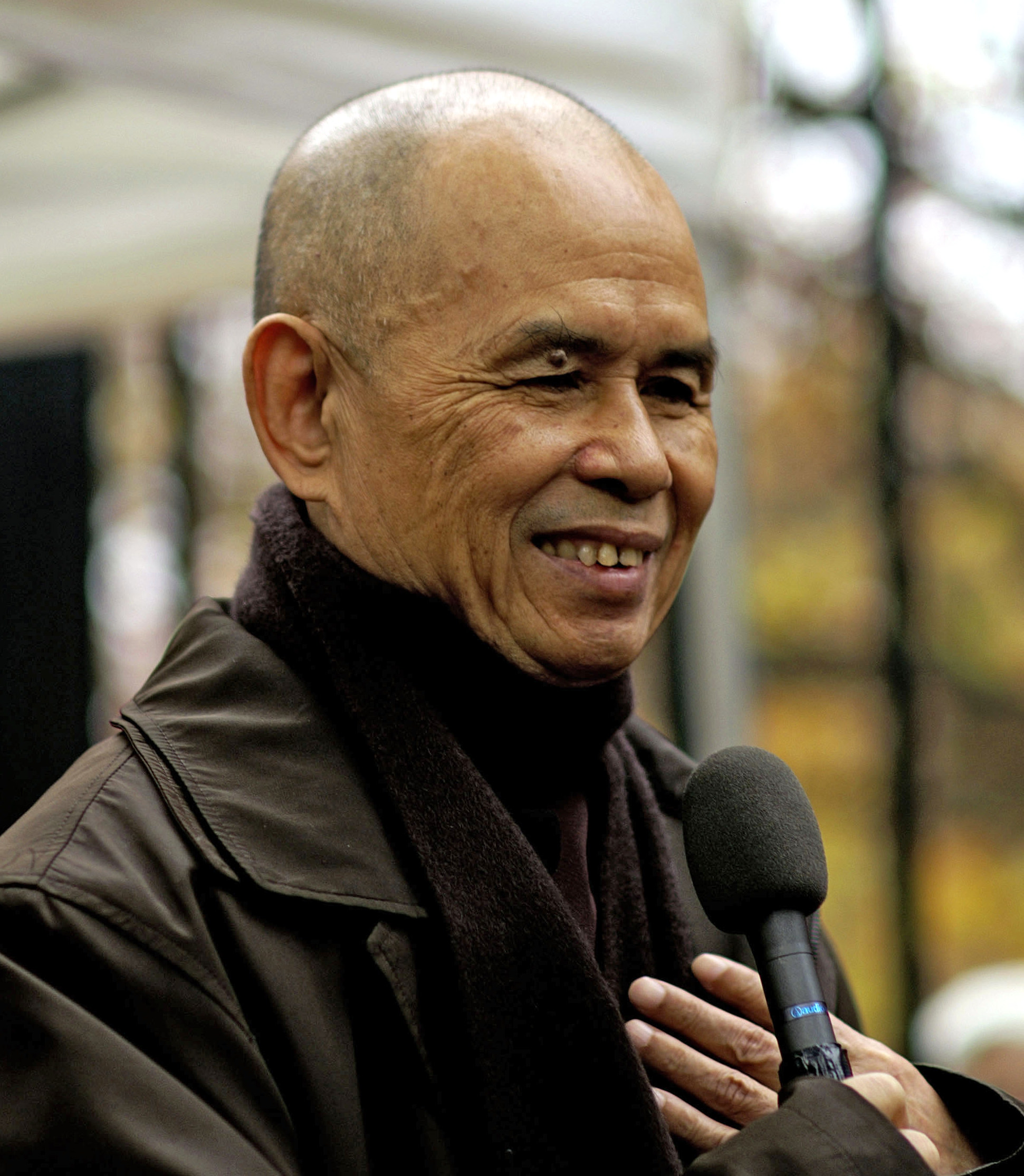

“We combine our breathing with our steps,” writes Thich Nhat Hanh, a renowned Buddhist monk who advocates walking meditation. “When we walk like this, with our breath, we bring our body and our mind back together.”

Once you have centered yourself in your body, aware of the harmony in your breath and steps, you can expand your focus to all your senses. “Listen to the birds” is a worn-out cliché, but for good reason: bird song is one of the most pacifying and magical sounds I’ve ever heard.

Notice the sounds, natural and man-made, along with the plants, the cracks in the sidewalk, the smell as you walk by freshly mowed lawns. Focus on a single tree, each distinct leaf, the way its trunk curves and knots around the edges. Breathe.

When you are calm and present, walking can also be the perfect opportunity to reflect, imagine, and simply notice your feelings and thoughts about yourself and other people. Some of my most profound insights about how to be a kinder, better human being have occurred to me while walking. Listening to music, in my experience, facilitates this process well, giving you your own introspective space, separate from the world.

I walk to class because it is my way of integrating meditation and reflection into my otherwise busy, mentally scattered life. Therefore, while bikes are sometimes necessary, I encourage you to try to walk to one class, club or meeting a day. Notice how you feel and what sticks out to you in your environment as you walk.

According to Thich Nhat Hanh, “Each mindful breath, each mindful step, reminds us that we are alive on this beautiful planet.” That, I believe, is why I walk: for the space and time to receive this reminder.

So walk to class, walk to dinner, walk to the post office, but take each step with the purpose of walking and nothing more.

Contact Avery Rogers at averyr ‘at’ stanford.edu.