A tree splits the frame, hanging languidly (but with backbone) over a dirt road. Embedded in its branches: a battered sign, demanding, CHRIST OR CHAOS?

Walker Evans (1903-1975) — photographer, sidewalk rambler and the subject of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s new retrospective — would perhaps say, “both.”

A connoisseur of faces, Evans’ work appears largely concerned with who or what we fail to notice — who or what, exactly, you walked by and didn’t take the time to study, to see. Though predominantly known for his work with the Farmland Security Administration (FSA) during the Great Depression, the show travels far beyond the 1930s. Though most exhibitions on Evans proceed chronologically, the SFMoMA retrospective is thematically arranged in two parts. A testament to the defined moment, Part I focuses on “many of the subjects that preoccupied Evans throughout his career, including … signage, shop windows, roadside stands, billboards,” while also including some of Evans’ most iconic work of the Great Depression and the New York City street. In a symbiotic but noticeably distinct change, Part II centers on Evans’ fascination with the “methodology of vernacular photography.” Evans emerges from both parts as a truth-teller.

Upon entering the gallery space, one passes next to a full-size triptych of Evans himself — a canonized form of the now popularized “photo booth selfie.” Yet despite the self-portrait having a somewhat grim cultural standing today, the saintly taste of the triptych lingers throughout the passages of the bare, white gallery. The vocabulary of the ordinary is what, Evans’ photographs suggest, define the American individual. His shots are not of grandeur or luxury; rather, they are simplicity composed: half light on a windowsill, a stilted smile, people on sidewalks who are not aware they are being noticed with such tenderness. The lack of a linear time progression magnifies the tonal bareness of the show: Chronology is impossible, and the viewer is forced instead to revel in the saintly minimalism of each photograph.

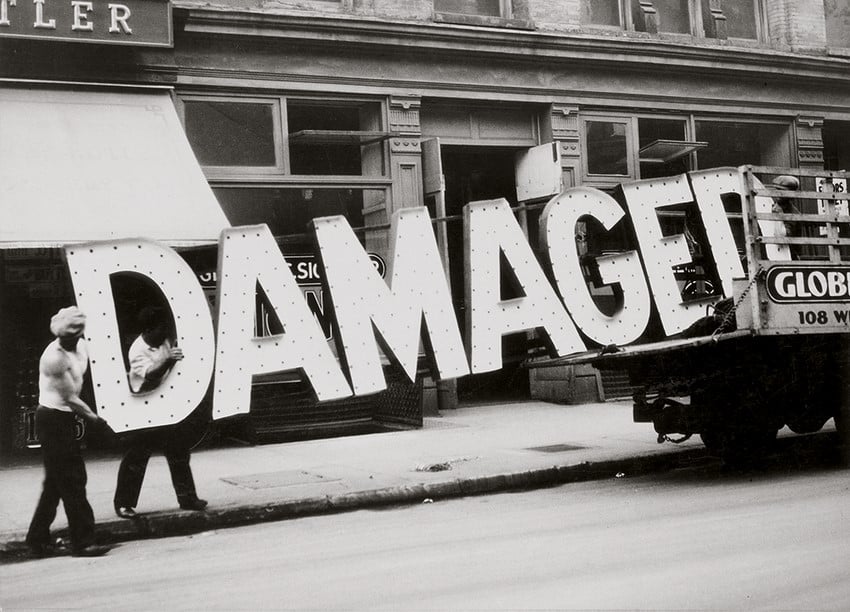

In one striking photograph, “Truck and Sign” (1928-30), Evans captures the fragility and possibly eternal condition of the American individual. In the picture, two workers in San Francisco load an enormous sign onto a truck. In large white lettering, the sign says only one word: DAMAGED. This word takes up the majority of the frame. It is central but crosses the picture plain non-symmetrically. Slightly deviating from a perfectly horizontal line, the tonality of the white letters is impossible to escape. The truth of this picture — its unapologetic nakedness, its blatant proclamation — almost punches one in the face. For it is not the men carrying the sign who seem to be damaged, but rather it is you as a viewer. You as a viewer are the one incapable of looking away, incapable of not feeling some deep resonance with the word Evans immortalizes. It is, without a doubt, impossibly sad.

Walking beside Evans’ subjects, the spectator finds an intimate self-parallel, as it becomes impossible to not see oneself in the prosaic nature of the work week, weekend picnic, Monday-night newsstand. His New York street photographs ring with the same tonal familiarity that his Depression area shots do. In this tribute to the miniscule, the ordinariness of the everyday shines. A master of contrast, in Evans’ pictures light and dark move as if in dialogue with one another — back muscles align convulsively, perfectly, as white sidewalk paint refuses to subsist on anything but geometric purity. Evans perhaps finds a kindred soul here in Ad Reinhardt’s abstract expressionist work, as both deliver a prominence to ideas of emptiness or smallness that equate themselves in full to something completely and utterly worth laying praise to. Indeed, something irreproachable emerges from the bare white gallery walls, something holy from the plain floorboards. Immersed in the ordinary, Evans promotes the beauty of the anonymous.

In Part II of the show, this anonymity gains the spectator’s full attention. Rows upon rows of portraits face the viewer but importantly, lose nothing in their collective display. Every face is prominent at once, an almost uncomfortably overwhelming experience as individualism collides with the reality of mass congregation. In this, Evans raises the window-shopper, park-bench-sitter, people-watcher to otherworldly status. The individual is rescued from the multitudes. With each singular face presented, something of the phantasmal lingers, as the saintly atmosphere Evans’ modern-day triptych first evoked continues to coat the gallery walls with the residue of something mystic languishing in each phantom shutter click and in our own blinking. An altar to the grace of the singular moment, Evans’ pictures—not only those done on film, but also some paintings done in tempera — ask us what it is exactly that we are working, searching, living every ordinary day for. In his exploration of the American vernacular, he reveals to us the state of everyday existence as we alone perhaps could not see it.

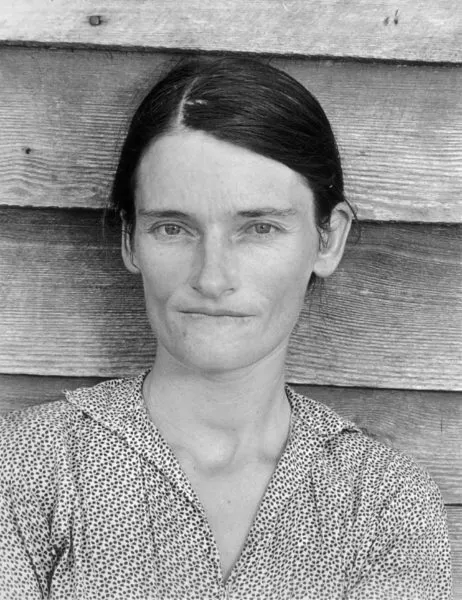

In one of Evans’ most famous pictures, “Allie Mae Burroughs, Wife of a Cotton Sharecropper, Hale Country, Alabama” (1936), a woman eases back against a shingled wall, staring with intensity at the camera. This picture in particular has captured the public eye precisely for its minimalistic nature. The subject, Allie Mae Burroughs, is plain. The utilization of black and white, while providing some contrast, does not deter from this overall understated-ness. With her lips compressed, face slightly asymmetric, hair pulled back tightly at the nape of her neck, Allie Mae is a model of grit, of a warmth that once endured but is in the process of drying up. The emotions on display here are ones stained with the poverty and brackish conditions those in Alabama had to endure during the Great Depression. Her eyes are as old as the wooden wall. Her face is defeated as her limp shirt collar is defeated. With this image, Evans takes an ordinary subject, one among many thousands, and in her discovers a defining icon for the state of the times, as if to say: Look! Look how sparsity abounds! And look at the nearly angelic humanity that trembles within it!

Shot on commission for the FSA, Evans became famous for pictures such as Allie Mae’s for their ability to intimately reveal the troubles of a despairing American landscape and populace to the viewer. A soul cannot walk by the portrait of Evans’ sharecropper’s wife without in some corner of his cerebrum feeling pain resonate. In Evans’ work, he prompts us to think on the hardships often associated with being human — he reminds us of hunger, of anxiety, of chaos, yet also, of the possibility of salvation.

Leaving Walker Evans, one feels an almost instinctive need to routinely assess every passerby. This intense desire manifests itself, however, into a building anxiety. It begs us to ask ourselves: Is my face lost on anyone beside me? Is anyone, in fact, noticing me? Will I be remembered? Do I even want to be remembered?

Walker Evans’ project was not one of a hobbyist collecting random people and random moments. His project was to teach us how to see the everyday so that we never forget a face. He leaves the spectator as one forced to acknowledge a converging of something saintly with something confusingly ordinary. Nothing escapes this convergence, as everything within the American vernacular is encompassed by it. It is not, after all, a question of Christ or Chaos. Rather, it is Christ meeting Chaos in the middle of the street. It is both, intermixed. And it is this permeation that infiltrates every single day of our collective lives.

Contact Mac Taylor at ataylor8 ‘at’ stanford.edu.