Few poets in human history have inspired such lasting devotion as Sappho. Yet, for the majority of Sappho’s readers over the millennia, her poetry, composed in the Aeolic dialect, has always been inaccessible in the original language. Translation has been intimately bound up with the reception of Sappho’s poetry for centuries. Until recent decades, however, English translations of Sappho have frequently obscured more than they revealed, heterosexualizing her expressions of desire to suit the sensibilities of their audience. While translators of Sappho today as a rule avoid such censorship of her work, modern translations nevertheless differ widely. In this article, I review four translations of Sappho produced over the past six decades.

Richmond Lattimore’s anthology “Greek Lyrics,” first published in 1955, includes nine texts attributed to Sappho, though in one case he acknowledges that this attribution is questionable. Best known for his translations of the Homeric epics, Lattimore’s style is characterized by a close attention to the syntax and meter of the original and the replication of these qualities in English as much as is possible. The resulting translation maintains the tension in Sappho’s work between the strict meter she uses and the much-praised directness of her speech. One drawback of this approach is that by replicating the structure of the Greeks, Lattimore’s translation has a sense of strangeness and occasionally even awkwardness, which those who first heard Sappho sing would not have heard. Take, for example, his rendering of the first stanza of one of Sappho’s most famous texts:

Some there are who say that the fairest thing seen

on the black earth is an array of horsemen;

some, men marching; some would say ships; but I say

she whom one loves best

Even taking this tendency toward awkwardness into account, Lattimore’s translation is excellent. However, he translated only a fraction of Sappho’s corpus, and for the rest we must look elsewhere.

Mary Barnard’s 1958 publication of “Sappho: A New Translation” revolutionized English translation of Sappho. Meter falls by the wayside in this translation; instead, Barnard prioritizes what she calls Sappho’s “fresh colloquial directness of speech.” Barnard translates the vast majority of Sappho’s surviving works, including texts which are highly fragmentary. When translating fragments, Barnard connects separated pieces of text without indicating any break in the English. Such treatment of the text is closer to adaptation than translation, constructing a new poem out of the fragments of Sappho’s writing. This makes Barnard’s translation unsuitable for most academic settings, yet its charm and power is undeniable: “Sappho: A New Translation” has never gone out of print. For comparison, here is Barnard’s treatment of the same lines as quoted previously from Lattimore:

Some say a cavalry corps,

some infantry, some, again,

will maintain that the swift oars

of our fleet are the finest

sight on dark earth; but I say

that whatever one loves, is.

Barnard departs dramatically from Sappho’s verse forms in her translation, and many translators after her have followed her example; today, though Sappho wrote in strict meter, she is often translated into English in free verse.

Anne Carson’s “If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho” is the most popular English translation of Sappho today and is used by the Structured Liberal Education program here at Stanford. Published in 2002, this edition’s main claim to fame is its comprehensiveness: Carson translates every fragment known at the time of publication (further texts have since been discovered), including those which are only one word long. The format of this edition, with the original Greek text printed facing the translation, makes it especially attractive to anyone who has some familiarity with Greek but cannot yet manage Sappho in the original. Unlike Barnard, Carson uses brackets to mark lacunae in the text, leaving the reader perpetually conscious of the fragmentary nature of Sappho’s corpus even as new meanings are suggested across the absences. (For an excellent discussion of this aspect of Carson’s translation, see Shana Hadi’s column “On sustained silences in Sappho and abstract expressionism.”) Carson’s book also includes a wealth of endnotes addressing her translation choices. Carson renders the lines quoted above like this:

Some men say an army of horse and some men say an army on foot

and some men say an army of ships is the most beautiful thing

on the black earth. But I say it is

what you love.

Carson’s translation is imbued with the sensibilities of modern English poetry. Her phrasing is fresh and direct without abandoning the form of the Greek original.

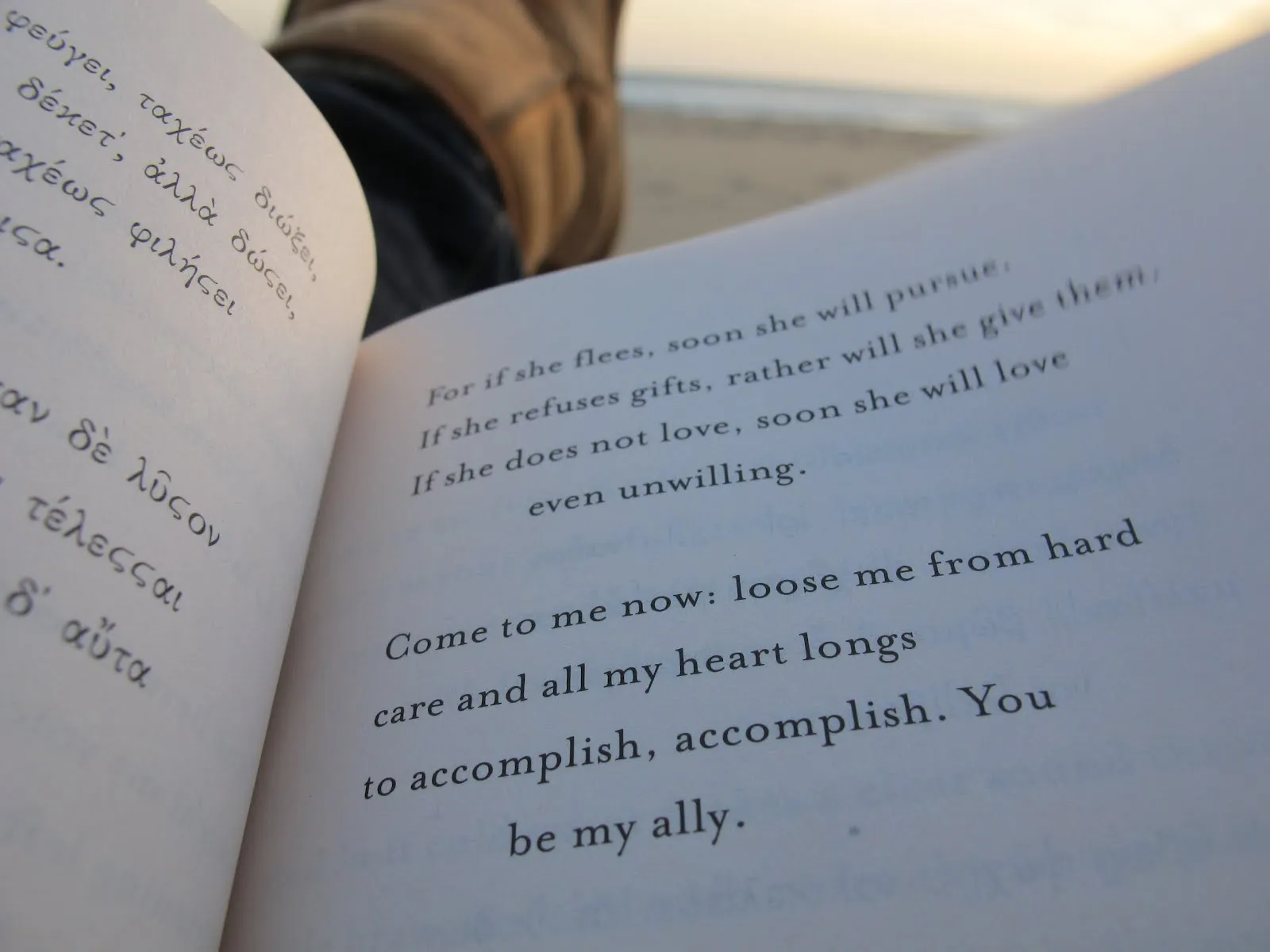

Aaron Poochigian’s 2009 translation “Stung with Love: Poems and Fragments” comes the closest of any translation I have ever read to capturing what must have been the experience of hearing Sappho perform. Poochigian renders Sappho’s texts in English rhymed verse rather than translating in free verse, as Barnard does, or echoing the original Greek meter as does Lattimore. Free verse translations do not capture the formal precision of Sappho’s poetry, while attempts to mimic the original verse form introduce a foreign quality not present for Sappho’s ancient audiences, since modern readers of English poetry are necessarily unfamiliar with the Greek meters Sappho uses, which can in any case be approximated in English only roughly. By choosing forms familiar to the reader, Poochigian is able to portray the delicate balance between metrical precision and originality of expression which has made Sappho perennially beloved. Poochigian supplements each text with copious notes on the facing page regarding translational nuances. He is not afraid to break with the traditional reading of a passage when the Greek suggests something different, as shown in his treatment of the comparison lines:

Some call ships, infantry or horsemen

The greatest beauty earth can offer;

I say it is whatever a person

Most lusts after.

Poochigian’s translation is elegant, his analysis eloquent and the whole book a delight to read. I recommend it without reservation and anticipate its influence on new translations of Sappho in the years to come.

Contact Emma Grover at ehgrover ‘at’ stanford.edu.