Sometimes when I sit down to write, a biting frustration courses through me. It’s a distinctive feeling — caustic, jittery, restless — seemingly without origin, not directed toward any particular external problem. The frustration, I realize, comes from within my body. I need to move, jump, run, dance. Nothing could save me but a long moonlight jog, a set of push-ups, a rave — iron, sweat, breathless heart-pumping.

This craving for exercise, when satisfied, is indeed a dependable antidote for the worst of writer’s block. Some of my most fertile ideas rise from the state of breathless wonder I experience after a long bike ride, a state in which I feel each particle of my body welded to the energized aura of the words I produce. I therefore wonder if there is something more than transactional in the symbiotic relationship between body and language. What relationship might they have beyond the simple boost of productivity one might accord the other? Is there a form of literary aesthetics of the body?

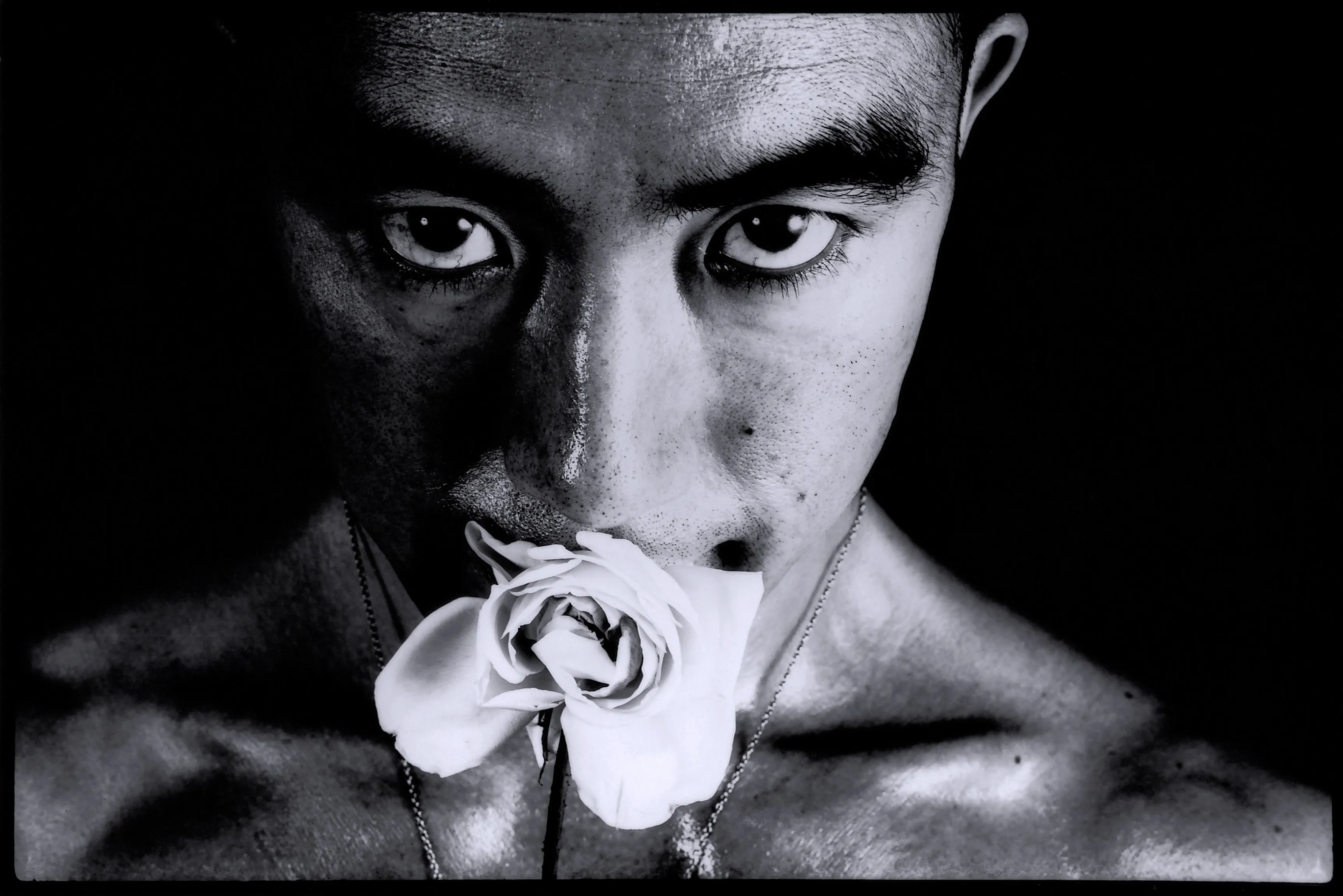

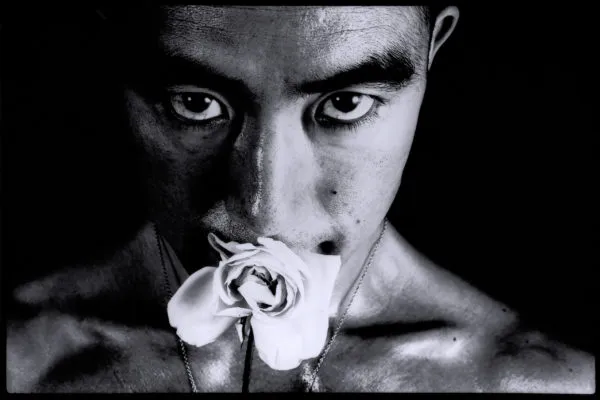

I first became seriously aware of this possibility while reading novelist Yukio Mishima’s autobiographical essay “Sun and Steel.” Mishima begins by creating a distinct opposition between the world of language and that of the body. If his body is an orchard, words are exemplified by termites, corrosively eating away at the wood, and more broadly, at the very substance of reality itself. This very antagonism, Mishima writes, is what propelled him not only to write novels, but to pursue his own bodily transformation, “to seek a kind of platonic ideal that would make it possible to put the flesh and words on the same footing.”

Mishima then goes on to describe the exact manner in which he pursued this ideal body. Beginning with his 10-year engagement with weight lifting, Mishima describes how his pursuit of “swelling muscles encased in sunlit skin” came to exemplify an intellectual fixation on the surface of sensory experience, as opposed to the nocturnal abstractions of a solitary thinker. In his words, “Why must thought, like a plumb line, concern itself exclusively with vertical descent? […] it seemed excessively illogical to me that men should not discover depths of a kind in the ‘surface,’ that vital borderline that endorses our separateness and our form, dividing our exterior from our interior.” Making his own body beautiful, then, was necessary to being able to think and write faithfully on matters of the surface.

As Mishima develops this journey further, his ideas morph along with his bodily experiences. The better acquainted he becomes with the pain and exertion involved in his physical pursuits, the more his thoughts on the body take on a tragic, morbid turn. The sun becomes associated not just with the surface features of beautiful tanned skin, but with thanatological transcendence: “A sun full of the fierce dark flames of feeling, a sun of death that would never burn the skin yet gave forth a still stranger glow.”

Death ultimately becomes the sole principle linking the fundamental incommensurability of body and mind, the dualism with which he begins the book. Mishima writes: “My solace lay more than anywhere – indeed lay solely – in the small rebirths that occurred immediately after exercise. Ceaseless motion, ceaseless violent deaths, ceaseless escape from cold objectivity […]” Exercise thus produces an experience of ecstasy, a momentary loss of consciousness, orgasmic dissolution.

This vision of the body as a vessel for intellectual and material transcendence is in many ways an intensely beautiful one. But it is impossible to ignore the facts of Mishima’s life and death in relation to this; in 1970, he chose to enact his own death by seppuku (ritual suicide) after staging a nationalist coup against the Japanese government. He was at the height of physical beauty at the time, and there is little doubt that the bodily training he describes and undergoes in “Sun and Steel” corresponds directly to his preparations for this tragic act.

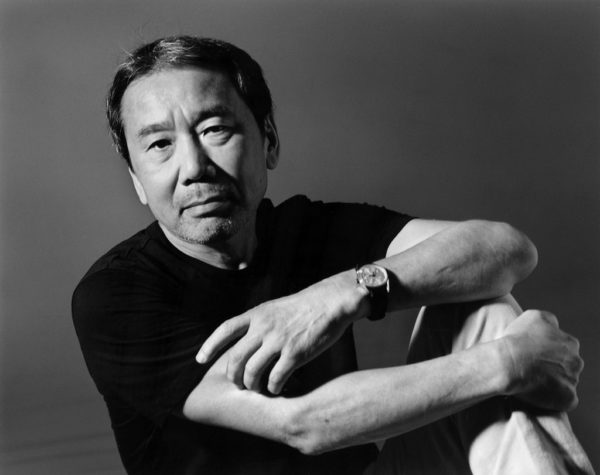

It is hard not to find his intense fixation on the mind-body dualism and its deathly erotics destructive, in light of this reality. Searching for an alternative narrative, I decided, several weeks ago, to pick up novelist Haruki Murakami’s memoir “What I Talk About When I Talk About Running.”

Murakami’s writerly voice, and indeed, personality, is so different from Mishima’s that it is almost shocking that they would operate under a similar interest in the relationship between body and text. While Mishima’s tone takes on the gravitas of a tragic hero, Murakami’s language is remarkably simple, and conveys an associated modesty. He has no avowed interest in any particular aesthetic ideal, and meanders, in the book, between different events in his life with seemingly little relation. Accounting for the finances of his jazz café, listening to the Rolling Stones, and training for a ultramarathon occupy the same plane of importance.

Of course, there are strands of continuity in Murakami’s narrative, one of which lies in Murakami’s assertion that his “only strength has always been the fact that I work hard and can take a lot physically. I’m more a workhorse than a racehorse.” Tenacity is perhaps the one thing Murakami values, the one thing he observes in both his writing and his dedication to running.

Like Mishima, Murakami concedes to a corrosive, or in his words, “toxic” view of language. Where Mishima writes of the termite, Murakami’s writes of the fugu fish, whose most delicious meat is most proximate to its poison. For him, novel-writing is a risky activity, in which “a kind of toxin that lies deep down in all humanity rises to the surface.” In order to engage with this dangerous material, energy and endurance are required. And where from? “You have to find that energy somewhere,” Murakami writes, “and where else to find it but in our own basic physical being?” Running, for him, fulfills this capacity for physical strength and endurance; it is a sort of “autoimmune system,” one which allows the writer to “resist the dangerous (in some cases lethal) toxin that resides within.”

Beyond running’s palliative effects, Murakami asserts that writing itself is an act of physical endurance analogous to the act of running. “Writing novels, to me, is basically a kind of manual labor. Writing itself is mental labor, but finishing an entire book is closer to manual labor. It doesn’t involve heavy lifting, running fast or leaping high.”

In the end, Murakami doesn’t have a particular investment in the body-in-itself, or, indeed in its particular effects on the content of his writing. Murakami’s body is no fount for specific aesthetic or intellectual concerns; it is simply a vessel for pain and endurance, a vessel which makes possible continual literary production. It points towards a modest and enduring life, while Mishima’s body points towards a glorious death.

Considering these two contrasting narratives together, it is perhaps instructive to ask which vision better fits any given reader’s experience. For me, personally, it’s easier to latch on to Murakami’s approach when I’m scrambling to write a throng of essays on tight deadlines, when I need to feel healthy and constructive. But on a day in which I am seeking to uncover what animates my inner desires, I’d perhaps choose to entangle myself with Mishima and his flurry of difficult, twisted desires.

Of course, there is no need to choose one over the other. Perhaps the best result of reading the two writers’ work in conjunction is the realization that the body and writing have a necessarily multifaceted, deeply personal relationship. The realization that an uncontrollable desire to get up and dance in the throes of midterm week is, in fact, an experience worthy of literary contemplation.

Contact Didi Chang-Park at didip ‘at’ stanford.edu.