Latino culture and California culture sometimes seem synonymous in the way that the two have fused to create dynamic and rich social settings around the state. Approximately one third of California residents speak Spanish as their first language at home. Obviously, the contributions of Latino culture can be seen by just observing with the naked eye. Why, however, do we not see the same representation of Latinos within artistic culture? Cary Cordova, associate professor of American History at the University of Texas at Austin, came to speak Tuesday at the second installment of the American Studies Art and Social Criticism Series. Cordova – an archivist, curator and former oral historian of the Smithsonian – is an outspoken critic of the underrepresentation of Latinos in the art world. Cordova’s newest work, “The Heart of the Mission,” traces her roots in the city of San Francisco and the role that the city has played in developing and displaying the work of groundbreaking Latino and Latina artists.

Cordova acknowledges the vast breadth and diversity of Latino and Latina work within the San Francisco Mission District, while also finding frustration with the lack of acknowledgement and representation within the art world at large. Throughout her speech Cordova drilled home a singular point: despite how important and groundbreaking the artistic work of Latinos in the Mission District has been, the San Francisco art world, and rather, the artistic community at large, has been frustratingly slow to desegregate and acknowledge the validity and accomplishments of the Latino artistic community.

Cordova opened her talk by reading from a 1973 editorial piece from The New York Times. Journalist Robert Hughes had written an op-ed about “vapid curation” of museums, in which he argues that museums are including questionable art simply for the sake of inclusion. The article is titled “And What About the Quota for Gay Militant Chicano Artists?” Hughes essentially dismisses Chicano and other minority art as illegitimate, claiming it is “noise” obscuring true and pure intellectual art. Cordova used this piece to frame her argument that the art world holds a longstanding contempt for non-western and minority artists. San Francisco, a city of diversity and opportunity, regularly excludes minority artists from artistic communities by not presenting or seeking out their work or including them in exhibitions, and thus cuts them off from the benefits and opportunities these collectives hold. Despite the roadblocks of Bay Area artistic politics and prejudice, Latino artists found their home within the Mission District.

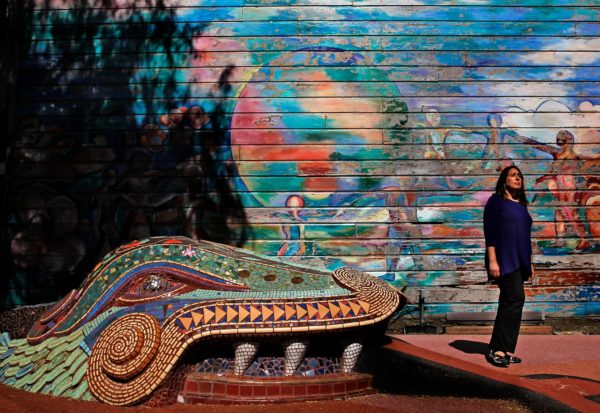

In a city like San Francisco, filled with counter culture and intellectualism, it can be difficult to pinpoint an artistic center. For the past few decades, Latinos have created their own center within the Mission District. Latinos were able to negotiate their own artistic politics by building publishing collectives, theatrical areas, galleries and spaces of their own. They re-scripted popular images for their own critiques and started movements for their culture. The most famous of these museums is Galleria de la Raza, founded by the Chicano movement in 1970 as a place for Latino artist to display their own work on their own terms.

As Cordova emphatically described the need for recognition of this flourishing of artistic creativity, she remarked critically on the artistic world’s ignorance of Latino contributions and art. In one story she told, a Latino artist walked around the National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C. The artist asked why they were no portraits of Mexican Americans in the gallery, to which a docent replied, “We don’t show portraits of foreigners.”

Many pivotal works of art have come from Latino artists. Rupert Garcia’s “Down With Whiteness,” a work almost unanimously praised by San Francisco art critics for its powerful imagery and impact, faced many barriers in being shown in museums that focused on traditional Western works. Eventually, Garcia’s work was shown along with disclaimers such as “These works are the opinions of the artist. They do not in any way reflect the opinions held by the institution of this museum and its staff.”

As Latinos faced this kind of pushback for their political work, a group of Latino employees of the Smithsonian wrote a blunt letter known as “Willful Neglect.” The letter detailed the ways in which Latinos have contributed to American art and the ways in which they are excluded from staff of museums and curatorial governance. Cordova agreed that exclusion of Latinos from museums is a systemic problem: even as diversity and equal opportunity initiatives present themselves more often in museums, boards of museums that have actual governance and power remain segregated and homogeneous.

At the end of her talk Cordova paused, choosing her words carefully. “At its essence,” she said, “the art world has not reckoned with Latino culture in an appropriate way.” In light of DACA, the proposal of Trump’s wall, and the horrific natural disasters wreaking havoc on Puerto Rico, it is more important than ever to acknowledge the validity and contributions that Latino artists have given to the art world. Galleries such as Galleria De La Raza gave way to burgeoning movements that have changed artistic history. The Mission District is a pivotal center of counterculture and artistic development that is largely ignored in the artistic community as a whole. As much as we feel that we have moved away from invalidating others’ perspectives and art, we find ourselves at a moment that feels a lot like Robert Hughes’s 1973 editorial.

Cordova finished on a cynical note. “We’d like to believe that history is a narrative of progress,” Cordova said. “As much as we want it to be, and as much as we may delude ourselves into thinking it is, it simply is not.”

Contact Natalie Sada at nsada ‘at’ stanford.edu.