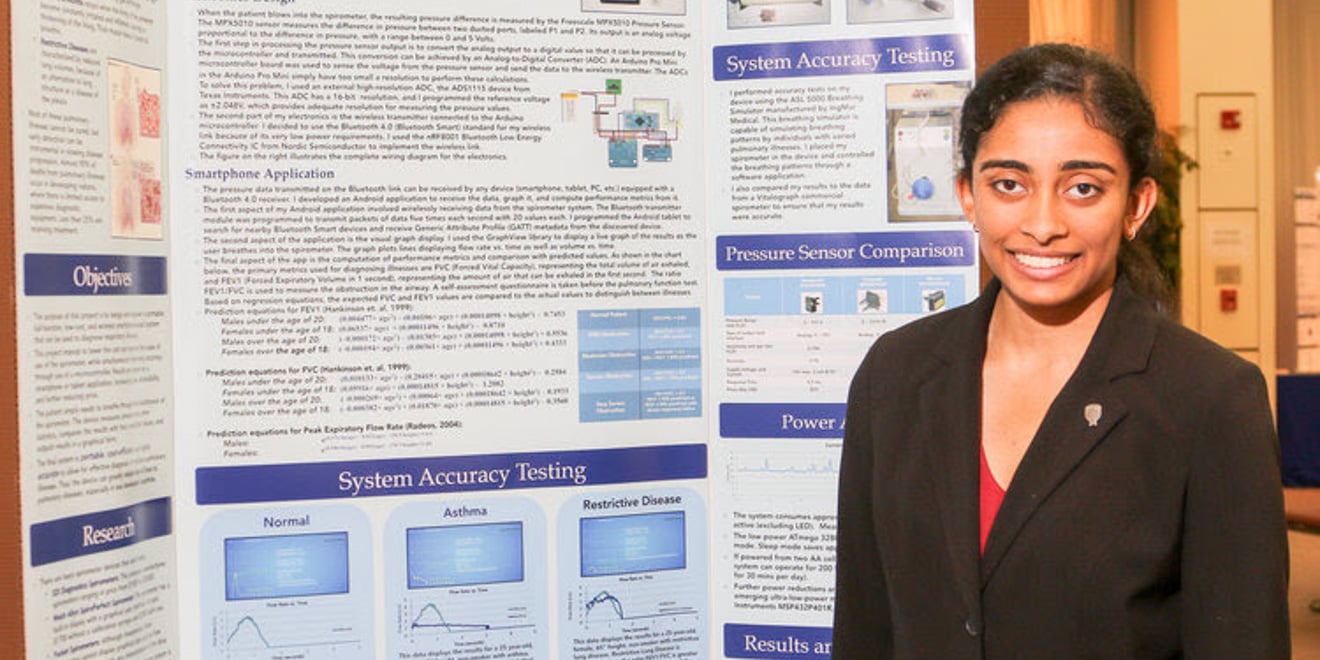

Maya Varma ’20 was named earlier this year to Her Campus’ 22 Under 22 Most Inspiring College Women list for her achievements in designing affordable health care technology. Her Campus, an online magazine for college women, picks 22 undergraduates nationwide to honor for their innovation and work helping others. In 2016, Varma placed first in Innovation in the Intel Science Talent Search, a prestigious high school scholarship competition, for creating a low-cost pulmonary function analyzer to diagnose respiratory problems. The Daily spoke with Varma about her past accomplishments and future aspirations.

The Stanford Daily (TSD): What made you decide to do bioengineering?

Maya Varma (MV): I started engineering in sixth grade, so I started participating in science fairs locally and then I started beginning-engineering projects, creating systems that could help people. From there my interest kind of developed into medical devices and specifically creating systems that could help patients around the world, especially those who do not have access to expensive technology. So my first sort of medical technology project was in eighth grade: I created a system that would test for foot neuropathy for diabetic patients. That was my first experience with it. It’s really fun; I got to present at the state science fair and I ended up winning first place that year, which was my first big science achievement. It got me really interested in the field in general and using technology to help people.

TSD: What did you start out building?

MV: I was just beginning to learn engineering skills, so in sixth grade I created a system that would be able to charge your cell phone and do a few other tasks just by moving this device back and forth. It was based on electromagnetic induction. In seventh grade, I started working on a system that would warn distracted drivers about a change in the state of a traffic signal, like from green to red, so that they would have time to stop. I actually ended up getting a patent on that a few years ago, so that was really fun.

TSD: What or who inspires you to do this type of work?

MV: Each of my projects sort of stems from personal experiences or an experience with a friend or that sort of thing. So for my pulmonary function analyzer project, I actually had a friend freshman year of high school who had a really bad asthma attack and had to go to the hospital. She was the one who first told me about spirometer devices and how they’re used, and [I had] never even heard of the term before. I researched it and found that there are a lot of issues with the system today and how they’re distributed around the world, so that inspired that project.

TSD: What problems exist with [spirometer access] today?

MV: For one, they’re very expensive. They cost thousands of dollars — so they’re not accessible in many poor countries where many of the deaths are happening. The other issue is that they’re big equipment that need to have a doctor there to interpret results. It’ll just give you a printout of a waveform or something and then a doctor will have to interpret that for you. So in many areas where the problem is at its worst, they don’t have access to this sort of device, so I thought I’d create something to help.

TSD: How does your spirometer differ?

MV: I basically 3D printed the foam head where the person blows in. Then I created an Android application that would accept that data and used World Health Organization statistics to calculate whether a person has one of five pulmonary illnesses. Basically, the difference is that the user uses the Android application, which drastically reduces costs because a lot of people have access to smartphone technology, and it also provides an interpretation of results for the patient. The other thing is that the 3D printing and the electronic system that I created [are] a lot cheaper than what exists today, so I was able to create my whole system for less than 50 dollars while the ones that exist today are thousands of dollars.

TSD: Is the system currently being distributed?

MV: Not right now because I’m still working on doing patient testing, making sure that it works as accurately as it can. I’ve already tested it with lung function simulators that would basically simulate breathing patterns, so right now I’m trying to test it on patients to make sure that it works correctly. Then I will think about possible distribution.

TSD: What other types of things have you done in the past? What are you most proud of?

MV: I’m definitely really proud of the science and research stuff that I’ve done. I hope that it’ll help people and it’s definitely a field that I’m looking into going after. That’s been my primary extracurricular activity throughout high school and last year. Besides that, I’m considering research now in college. I’m working at a research lab… It’s a bioinformatics lab, so I get to continue the idea of using my technology skills to help in the field.

TSD: How has going to Stanford so far influenced your knowledge or your career?

MV: I’m really happy to be at Stanford, especially because Stanford is located here in the Bay Area, and there’s a spirit of innovation everywhere. They inspire people really to think outside the box and try to create products that will change the world. So many great startups and companies have come from people who have went to Stanford, so I think that I have so many opportunities here to learn as much as I can, so that in the future I can continue to create this sort of impact.

TSD: What issues concern you right now, whether it be in health or just the world in general?

MV: One of the issues that really interests me right now is the general lack of access that patients have for the diagnostic systems that they need, so a lot of things like prosthetics, glasses, prescription medication — stuff like that [is] not very accessible at all to people who are most suffering from these problems. There’s a huge disparity in health care and how products are distributed around the world, so I’d like to help shift that a little bit by creating systems that will be affordable for everyone.

TSD: What would be your advice to other students looking to get into the engineering field or develop their own devices?

MV: It’s really important to look for problems that affect you or your community in some way so that you will have something to motivate you to create a system. Another piece of advice is to keep persevering because engineering is not easy, and you’ll always have systems that don’t work or run into issues while developing, so it’s important to not give up and to keep improving.

Contact Ryan Tran at rtran56 ‘at’ stanford.edu.