If you are reading this, you are probably a human being.

But what distinguishes you — whoever you are, dear reader — from other human beings? Is it the pattern of electricity circuiting your brain, the arrangement of your neurons and their delicate dendrites and axons or perhaps something that cannot be fully rationalized by neurobiology alone?

This question of “you” has been pondered through all means of philosophy and literature (and by myself during late night showers at 3:00 a.m.), and undoubtedly the only conclusion is that there is none. Because of this, you could stop reading, as the answer is unlikely to change within the time it takes you to finish this article. But if you keep reading, perhaps you’ll consider that what great works of art can offer us is an insight into the question itself.

Vibrant paintings, fluttering poetry and the immersive novel all have their places in my heart, but it is the simply elegant short story that is my bread and butter, particularly due to its ability to communicate mind-opening ideas with an average of a fifteen-minute read. (From the perspective of this amateur writer, a good short story can do so much with so few words.)

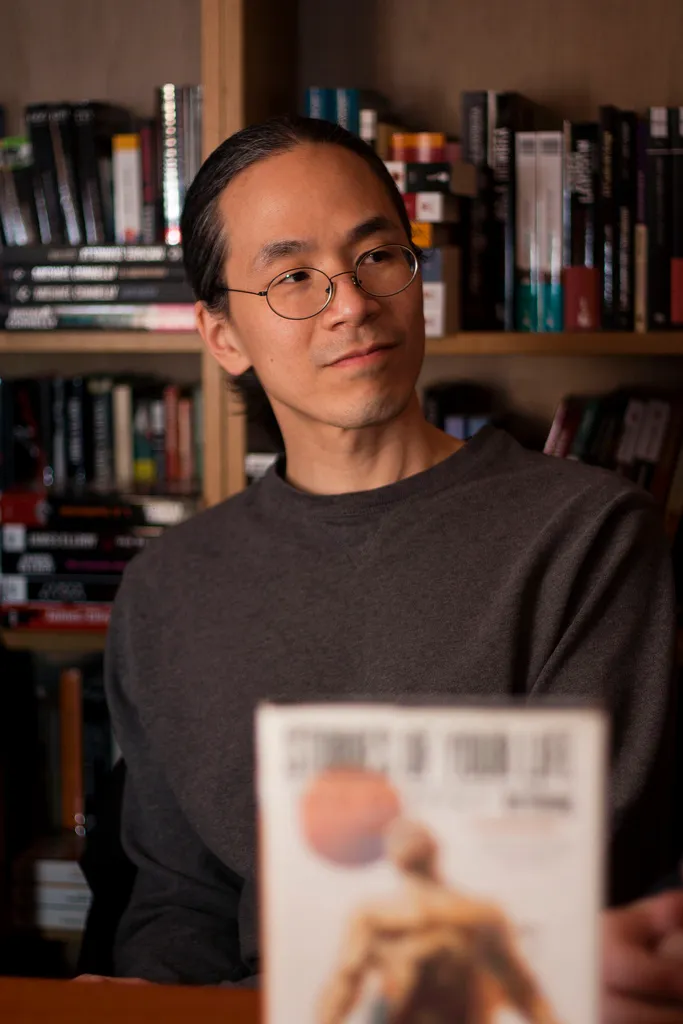

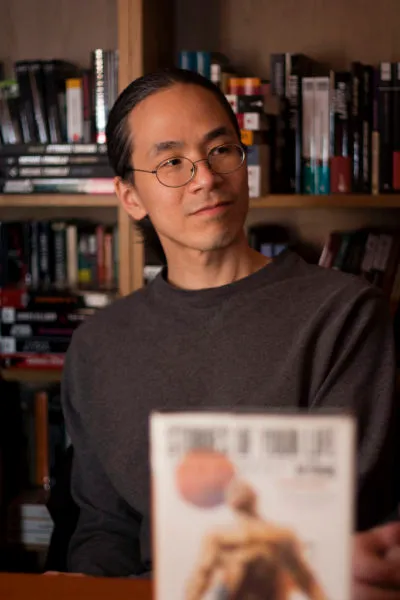

Ted Chiang, someone I truly admire, is a true master at this craft: besides winning four Locus, four Nebula, and four Hugo awards, his novella “Story of Your Life” was recently adapted in 2016 into the critically and commercially successful film “Arrival.” (However, I would like to announce that I found him before he was that cool.) Overall, his wisdom and clarity of thought pervade his every work, especially his short story “Exhalation” that ponders human individuality and human existence through a skillful use of allegorical elements.

From its first few words, we are introduced to an alien world with living creatures made from mechanical parts and brains of gold foil and air tubules, with lives sustained through inhaling argon from their planet’s core through their lungs. The narrator, ever the scientist, decides to dissect his own brain to learn more about the encoding of memories in his brain and discover how, exactly, his thoughts created his very self. By doing so, he realizes that instead of the common hypothesis that thoughts are inscribed on the flaps of gold foil, it is the very air (argon) itself moving through the gold that forms their thoughts and personalities through the pattern of aerial movement.

Considering such a metaphor in the context of neurobiology could be a fascinating discussion — current theories about human cognition do consider the idea of patterns of neurons or neural synapses “storing” thoughts or memories. Likewise, the malleability of changing the relative positioning of flaps of gold foil in the story reflects how easily (relatively) our own thoughts can be shaped and formed by our environments and experiences.

But another takeaway from the story is the narrator’s willingness to risk his life through dissecting his own brain, a sign of great ambition and dedication to his craft made particularly noteworthy due to the significance of his discovery that would change the field of science on his planet. Truly, can you imagine holding your brain — your very existence — in the palms of your hands, knowing full well that the slightest twitch could injure you permanently?

However, despite the narrator’s discovery of the upper echelons of such neurobiological knowledge, the story itself is not necessarily a happy one. Part of his realization means that with all the argon drawn from their planet’s core to sustain himself and others, the air pressure above ground is steadily increasing and eventually the air pressure of the planet’s core and the above world will reach equilibrium. In this alien world where air flow depends on air pressure, stasis means death, and eventually, he and his planet will run out of time. Similarly, as the narrator’s world gradually reaches stasis, it can be startling to consider that perhaps our own planet will be on its own way if we don’t expend the necessary effort to quell climate change and the like.

But instead of living in fear, participating in denial groups or rationing his air to the point that he must remain motionless, the narrator chooses to keep living, working and breathing, impending deadline and all. Though he has less time than anticipated, he remains grateful that he even has the chance to live, ephemeral as it may be. This in and of itself can be a mantra for living a meaningful life, even when you have only so many years to make a difference.

All questions and possibilities, but no concrete answers, “Exhalation” incites more theoretical possibilities than it solves. Nonetheless, the role of literature is not necessarily to prescribe solutions but to offer their readers something — an idea, phrase, identity or more — to take away.

And in this way, I will leave you with some distinctive parting words from the story, and I hope this fragment offers a glimpse of the tale’s subtle brilliance. As the narrator writes, “Contemplate the marvel that is existence, and rejoice that you are able to do so. I feel I have the right to tell you this because, as I am inscribing these words, I am doing the same.”

Contact Shana Hadi at shanaeh ‘at’ stanford.edu.