Reading Karl Ove Knausgård’s newest book, “Autumn,” is like drinking warm milk with honey on a chilly night. Each page is thick and dense and sweet. It’s a far cry from his previous work, which might be best characterized as a rich, peppery shot of whiskey (or six). In this epistolary masterpiece, Knausgård builds sweet yet grisly fairy tales from the bricks that make up our days – from the sun to stubble fields and from porpoises to piss. The book examines the world piece by piece with a sharp, sincere magnifying glass. It’s smooth and delectable as it slides down the hatch.

Between descriptions of shrunken gum brains and wasps portrayed as knights dressed for battle, Knausgård adds a rugged charm to each brief burst. No chapter is longer than three pages. Addressing his unborn child, he describes to her a little moment in his day, handling each subject with profound weight. He writes of frogs that look like roadblocks and petrol puddles that mirror nebulas. In typical Knausgårdian fashion, the book is a measured blur of fiction, philosophy and personal narrative.

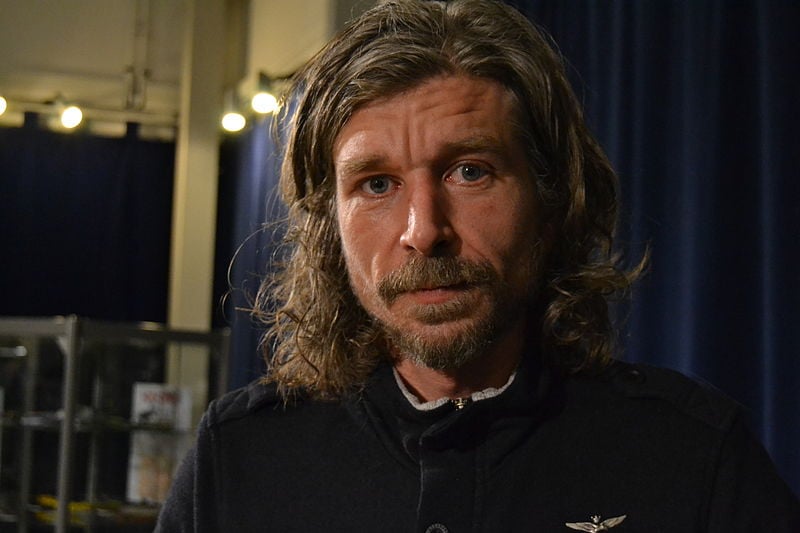

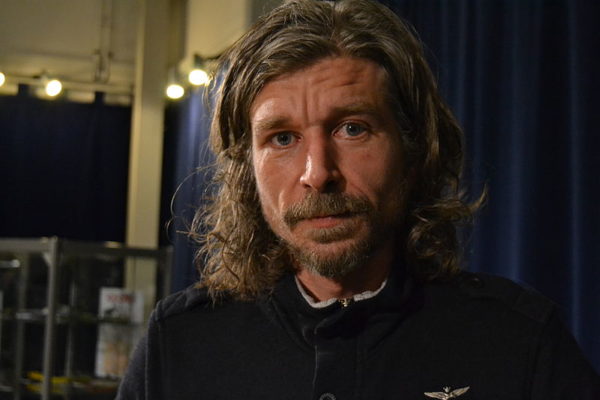

The undertone of the books is definitively masculine. Knausgård’s status as a contemporary literary mastermind is cemented by his macho persona. A tall, rugged Norwegian with icy blue eyes, sharp cheekbones and pensive frown, his image is almost always refined by a leather jacket or a cigarette. He speaks with seriousness and intention and his prose is heavy with a similar gravitas. Literature, he once claimed, should be ruthless.

I’m almost resentful of his immense literary aura. When I met him last year, he was as somber and striking as his latest book. He towered over the room and spoke with a deep, slow resonance. Everybody listened intently. As a woman, I’m envious he doesn’t seem to have to lift a finger to be taken seriously. His prose, like his presence, commands respect. Knausgård embodies the age-old image of masculine genius. He is the haunted, brilliant artist gazing out into the icy fjords.

“Autumn,” however, is chock-full of his reflections on nature, with industrial, historical and especially domestic influences sprinkled throughout each spout of a chapter. He writes of the worms and the rot but also of the light and the taste of crisp apples. Knausgård seeks out wonderment as a child would. After putting the book down, my walks to class seemed a little more exquisite. I thought about the strained arches of the pines and listened to the crunch of the carrot-colored leaves underfoot. I reflected sagely on a dead bird carcass, tattooed with bike tracks, that lay in the shadow Hoover Tower.

There is violence and chaos packed into the pages, for of course it is Knausgård we are talking about, but these instances are muted. In every book of the “My Struggle” saga, the Norwegian’s notorious autobiographical six-book epic, example of his world’s bloodshed and turmoil are included in gleaming heaps like diamonds in a mineshaft. In “Autumn,” the more hostile concepts are integrated and indistinct. Knausgård approaches a strange tranquility where vivacity and morbidity merge into a fluid, expansive puzzle. There is an astounding lack of friction between such weighty ideas. His writing maintains a sort of balanced purity, not in that it is without grime or free from agenda, but in that it is steadfastly sincere and equable. Knausgård does not force you to distinguish the beautiful from the decrepit; they are one and the same.

At the same time, Knausgård doesn’t push any real boundaries; the most profane subject the book brushes upon is oral sex. There is no exploitation of his closest relations for the sake of truth or brooding internal battles over the murderous elements of human nature. The book isn’t lacking in intrigue, but “Autumn” delivers softer, more select blows on a backdrop of apparent domestic harmony. The finished product has far less of the raw vitality that characterizes Knausgård’s prior work. Even the emotions Knausgård narrates are less intense and more thoughtful. Though striking and artful, “Autumn” lacks the burning, iron honesty of its predecessors.

I want to live in the a world where strangers’ eyes are “little lanterns of life” and toilets are “the swan of the bath chamber.” Knausgård coats the everyday world with a crackling magnetism and infuses each page with an inverted grace. The lovely, scattered illustrations of Vanessa Bair further complement the book’s compact snippets of beauty. I am already keenly awaiting the other three seasons of the series as the winter cold begins to sink its teeth in here.

Contact Gracie Newman at sgnewman ‘at’ stanford.edu.