To speak of habits is to imply a certain slightness. Usually, they suggest only a small deviations from normal behavior, and most things we call habitual are ultimately benign. What if, however, we replace the word with a less trivial synonym? Jennifer Ratner-Rosenhagen, who has written popularly on habits, substitutes “tick, obsession and addiction” to give gravity to the subject. Though these words are certainly not equivalent, we’re beginning to learn that their underlying mechanisms are much the same.

The term which unifies them all is “behavior.” In Skinnerian behaviorism, a behavior is a conditioned, largely automatic response to a stimulus. For medical purposes, this definition is taken at face value. Yet, the public often associates any form of a behavior with a choice, albeit a difficult one.

This understanding is going to have to change in the coming years because Skinnerian behaviorism is making a sudden comeback, with both positive and negative consequences. Among the benefits: Medicine’s embrace of behaviorism has allowed for the treatment of conditions for which nearly nothing else has worked. On the other hand, behaviorism can be used in marketing or social media to keep people coming back, whether or not it’s good for them. Both cases give contemporary importance to Skinner’s ideas and require that we take their impact into account in everyday life.

On the upside, medical professionals are using behavioral strategies to curb the effects of seriously detrimental behaviors. They do this in two main ways: either by helping people change their response to a stimulus, like a cigarette or unhealthy food, or by changing their environment through a “lifestyle modification program.” These practices are collectively called behavioral therapy, and they’ve proven in many cases to be more effective than conventional programs.

Americans are using many of the same strategies through popular habit-shaping apps like Lose It and the Apple Watch’s Breathe. We use these apps because we acknowledge that some habits are too hard to break on our own. Luckily, these apps work without much active effort on our part because they use conditioning to undo previously wired behaviors.

But if medicine has shown us that behaviorism really does work for our own good, we must also be wary of its potential for control. Recently, there have been fears that media giants are conditioning people towards technological addiction.

That proposed conditioning becomes especially troubling when we consider that social media platforms like Facebook exert considerable political influence. We’ve recently learned of attempts to spread propaganda by many different agents, including Russia and China. There are debates over what Facebook should or shouldn’t promote — those decisions being so important as to possibly sway elections.

However, it’s a serious claim to suggest that someone is toying with the population’s minds to keep them using a product. It’s even more serious when we suggest that this is shaping democratic outcomes. As I will demonstrate, however, it’s not out of the question.

It’s no accusation to suggest that Facebook stays afloat by spiking people’s happiness in various ways; any lasting product has to do this in order to maintain engagement. Yet, Facebook seems to have this method of retention down to a science. In the third quarter of 2017, its active user base exceeded 2 billion people. As only 47 percent of people globally have Internet access, the majority of adults online are actively using Facebook. That is to say, one single platform has got most of the Internet hooked.

The question is: How? The answer is problematic.

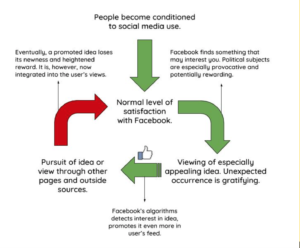

The concept of the hedonic treadmill informs us that happiness is cyclic and will return to a baseline without consistent and novel rewards. When rewards falter, people often stop engaging in a behavior, which, in this case, means not using Facebook. The platform’s goal, then, is to deliver frequent rewards to users. We’ve all heard about the dopamine spikes associated with likes, the randomness of which is especially rewarding. This is not enough, however, to maintain Facebook’s extremely widespread engagement. Likes are nice, but they’re the same every time, and rarely is their reward taken very seriously. Instead, Facebook’s potential as a media outlet has made it so successful.

When people use Facebook to receive content from news organizations or popular figures, they become much more invested in the platform and the rewards of using it become personalized. As it turns out, political content is especially provocative and so a highly effective tool to keep people coming back. As a result, it’s all over Facebook. The variability of political advertisements, which Russia purportedly used to sway the election, also helps to ensure regular spikes because it provide pleasant surprises. This is a known phenomenon of the reward system: We are more likely to repeat a behavior if it gives greater satisfaction than anticipated. Hence, users are even more likely to come back to Facebook for similar types of advertising and political exposure.

It’s difficult to say whether Facebook itself is promoting political content, or if it’s just most effective in getting people to continually use the service and so is employed by advertisers and pundits. Whatever the case, people who are continually exposed to that content are likely to create a monolithic feed in pursuing a line of political thought that they either already agree with or are pushed to agree with early on by political exposure through Facebook. Neither leads to healthy, two-sided political discourse. Instead, this mechanism has polarized politics and pigeonholed people into a closed system of belief.

As a point of clarification, most people are exposed to multiple perspectives through people they actually know on Facebook. Of course, the platform can’t change who you’re friends with, and so the issue is less black-and-white. Nonetheless, a constant influence in one direction amidst intermittent disagreement will still push some people into a political camp. In recent elections, which have been extremely close, every vote has mattered, and that’s why political agents are willing to spend so much on political ads, even if they only convince a few people. Moreover, 26 percent of people have unfriended (or blocked, hidden, etc.) someone they disagree with politically, isolating their own worldview.

None of this is an assault on Facebook’s ethics or intentions. Really, Facebook is just ahead of the curve, whereas few people are actively considering the impact of behaviorism. All of the companies gaming it are at least as complicit in this problem; Facebook’s platform has only enabled them. What we need to do is realize the growing power and use of behaviorism. Fears over its potential can no longer keep it out of public discussion; it’s already in use throughout society. Instead, those fears must make us weary of its misapplication.

Contact Noah Louis-Ferdinand at nlouisfe ‘at’ stanford.edu.