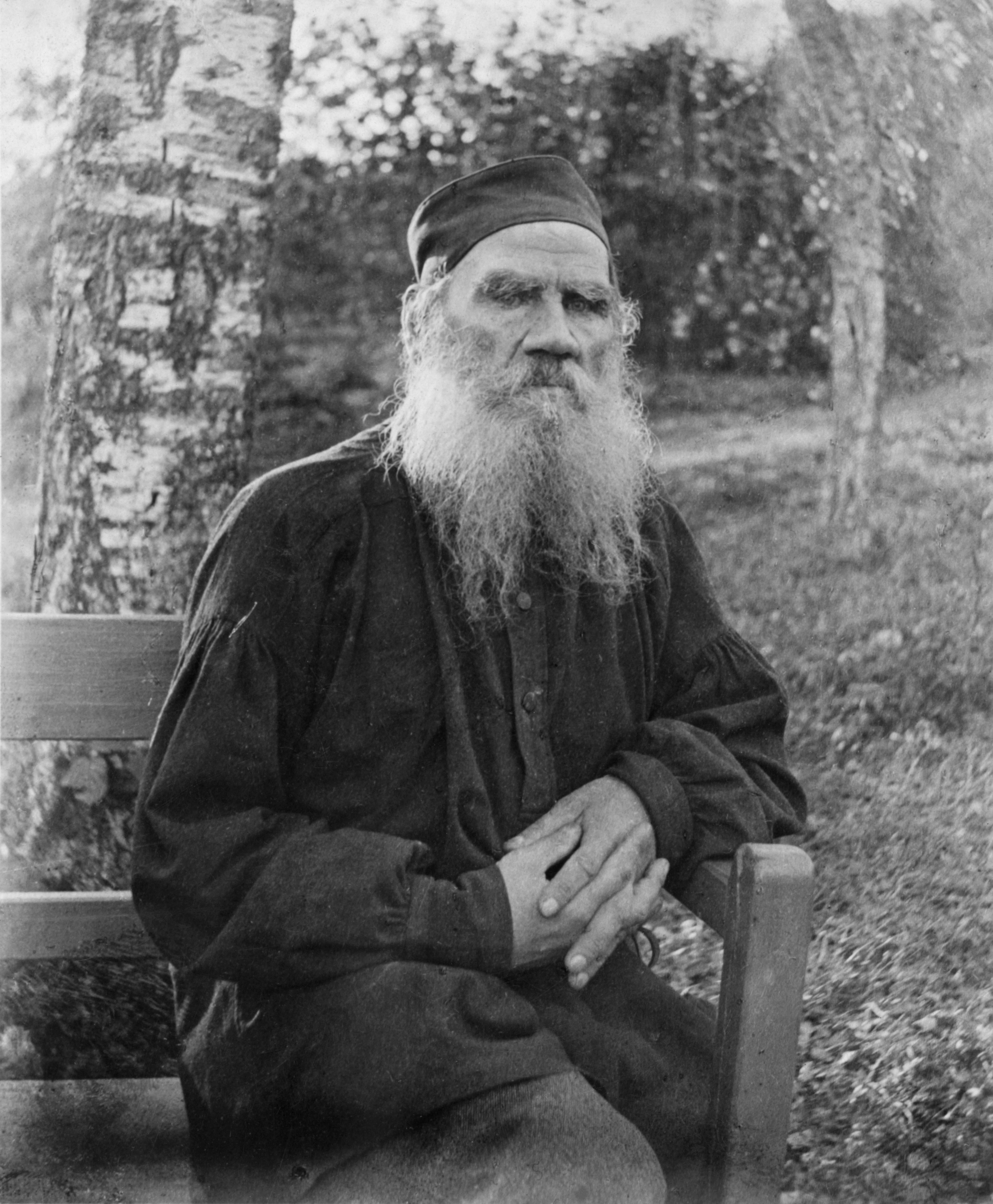

With Thanksgiving having just passed, I find myself recounting my blessings, while also reconsidering my priorities and the trajectory of my life so far. (Admittedly, the whole trend of “figuring out your life” is probably quite common for college students, but let me wallow for a little longer in this article.) Reading often helps me take my mind off of these very real concerns, but then again, I often gravitate towards works that actually prompt my questions further, like Leo Tolstoy’s novella, “Death of Ivan Ilyich.”

Considered one of Tolstoy’s masterpieces in his later life, particularly after his religious conversion, the novella presents a consideration of the “good life,” and if an individual can separate the artificial from the real. It begins with the death of none other than Ivan Ilyich, and then chronologically traces his lifespan from birth until his bittersweet end, throughout which he grapples with the meaning of his life. While he wastes away in bed from an incurable disease, he asks himself, “Maybe I did not live as I ought to have done … But how could that be, when I did everything properly?”

Ilyich recognizes an ever-present void in his understanding, as the idea of living “properly” continues to perplex him even on his deathbed. Already, he has fulfilled the role of “phoenix of the family” by attaining great heights in his career as a judge, marrying a well-educated and sociable woman, raising a respectable family and living in great comfort in a bourgeois residence where his greatest concern is the curved cornices of his red curtains.

However, despite Ilyich’s dedication to his respectable career, his awards and possessions seem to flow out of his fingers like grains of rice. For all his ambition, his personal needs are neglected; his wife and daughter fail to understand him beyond his role of “breadwinner.” What else can he call his own besides false friends who care more about their career promotions than his genuine well-being? Who can truly understand the plight of a man dying? He is a man who must exhale his last breath alone.

In this way, an interesting schism forms between the external and internal life, and Ilyich realizes, perhaps too late, how his focus on outward success has led him into this state of unease. In Ilyich’s last few weeks, only Gerasim, his butler’s younger assistant, cheerfully aids him in his more embarrassing activities, like excremental functions. While his wife bids him goodnight with a kiss and then leaves, Gerasim, a “clean, fresh pleasant lad,” props Ilyich’s feet on his stout shoulders so that Ilyich can rest more peacefully for the whole night.

Gerasim, the allegorical representation of the genuine, is who Ilyich turns to for succor in his final hours. Ilyich’s family is devoted to parties and what Ilyich can provide for them, but Gerasim chooses to give of himself so that he can ease a dying man’s pains. Later, Ilyich pronounces, “It is as if I had been going downhill while I imagined I was going up. And that is really what it was. I was going up in public opinion, but to the same extent life was ebbing away from me. And now it is all done and there is only death.”

Though these words are from a work of literature, the sentiment rings true, and in my mind, I see the image of a distinguished Russian judge draped on a velvet couch declaring that his life was wasted. Dramatic, but an effective message. Indeed, Ilyich recalls that his happiest days were those from his childhood, in which he could enjoy the pleasures and joys of youth without scrambling for advancement. Rather, it is his later years that are filled with grubbing for promotions and affection, forcing him into a hollow shell of materialism instead of acknowledgment of the heart.

Only in his last few moments can Ilyich embrace death and become spiritually reborn, as hinted by the aforementioned words “phoenix of the family.” But despite the value of his ruminations, he dies cognizant of his ultimate failure to pay proper attention to what mattered most to him – happiness. (The only time he associates the word “happiness” in relation to his life is for memories of his younger days.) Though he eventually finds peace with his death, the fact remains, he passes away with a life unfulfilled.

Not to cast a morbid tone on your day, but even though it is too late for the fictional personage of Ilyich, there is still time for you to choose how your life will unfold. What do you value most? On your deathbed (hopefully many years from today), what will you regret, and what will you want to change about your life right now?

Contact Shana Hadi at shanaeh ‘at’ stanford.edu.