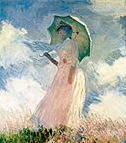

When I was younger, I owned a coloring book of 19th-century paintings, among them Van Gogh’s “Bedroom in Arles” and Monet’s “Study of a Figure Outdoors: Woman With a Parasol (Facing Left).” What struck me most in the Monet piece was the solitude and stoicism of the female subject, her skirt brushed with blush and ivory as it blew in the breeze and her gaze pensive and controlled, like porcelain. Carol Ann Duffy’s 1987 poem “Warming Her Pearls,” dedicated to Judith Radstone, somehow seemed, upon first reading, equally impressionistic; its subject is also alone, except for the audience, and surrounded by blurred words and girlish colors. If “Warming Her Pearls” is a painting, then, the four-part poem “Martha” from Audre Lorde’s 1970 poetry collection “Coal” is a photograph, a kind of memoir of Lorde’s former (female) lover’s recovery from a car crash that subsequently publicizes, for the first time, Lorde’s sexuality. While the majority of “Martha” handles homophobia and societal injustice, the second section of the poem, “Martha Pt. 2,” is, like “Warming Her Pearls,” more restrained, tender, like skin rubbed raw by the wind. The protagonists of both poems are creatures of containment, of both imagination and imprisonment.

“Warming Her Pearls” and the “Martha Pt. 2,” in particular, are poems concerned with the disconnect between external appearance and internal truth, and as such it’s fitting that their stanzaic construction reflects precisely the conflict between form and content. Both poems’ stanzaic design – their enjambment, their length, their verse division – are formal mirrors to themes of loneliness, unrequited love, deception in relationships and social taboo, and they’re largely differentiated only through tone. The poems’ stanzas are reflective of their characters’ coping mechanisms in times of crisis, and both contend with social hierarchy between lovers and struggling same-sex couples.

The rigidity of the four-line stanzas in “Warming Her Pearls” – a poem that explores the nexus of classism and closeted same-sex relationships in a vaguely Victorian time period – physically embodies the social severity and self-regulation that its protagonist must practice as a servant; it is an extension of her obligation to operate within gender roles and the social position of the world in which she lives. Lines with abrupt ends – “enjambment” – manifest the character’s inner struggle with the classism, heteronormativity and internalized homophobia of her everyday life. By continuing a phrase beyond the end of a line, Duffy invokes a sense of incompletion and self-restraint, of an unfinished narrative that, in the speaker’s ideal world, has multiple endings. The speaker is hopeful, longing for her mistress’s return from a party and idealizing that time with her, but reality ruins that the illusion in the next line by reminding her of her subservience: “[My mistress] bids me wear [her pearls], warm them, until evening/when I’ll brush her hair.” The poem’s overall lack of rhyme and meter in an otherwise traditional stanzaic format likewise contrasts with lyrical compositions like lullabies or fairy tales, further emphasizing the poem’s disillusionment and loneliness in place of a “happy ending.” The fragmentation of phrases such as, “I see/her every movement in my head … Undressing,/taking off her jewels,” highlights the narrator’s warring fantasies and self-control, while her confession that she “dream[s] about her [mistress]” and she “burn[s]” is a rare instance of self-indulgence.

The lines in Lorde’s “Martha Pt. 2,” in contrast, are chaotic and irregular, channeling the poem’s sense of disorder and the protagonist’s powerlessness. Unlike the narrator in “Warming Her Pearls,” Lorde’s character is more concerned with regulation of another than with regulation of the self. By splitting the poem into three stanzas, each stanza concretizes a train of thought: one is about Martha’s distance from her children (“but you have forgotten their names”), one about forgotten truths (“yes I did live in Brighton Beach once”), and one about their mutual future (“I do not know if we shall ever/sleep in each other’s arms again”), and the stanzas are all threaded through with the ache of Martha’s forgetfulness. Enjambment, here, is an incessant internal monologue, one that’s prompted by the fear of an uncertain future – compared to the certain but unsatisfying future of the couple in “Warming Her Pearls.” Lorde’s poem explores her speaker’s vulnerability through the vehicle of another’s, while Duffy’s instead does so through another’s invincibility.

These formal differentiations are further underscored by the poems’ tones; their diction and sentence structure infuse “Warming Her Pearls” and “Martha Pt. 2” with private ardor and private grief, respectively. Duffy’s character is wistful but resigned, intensely restrained but desperately imaginative as she fantasizes about an affair. Both she and her mistress are steeped in sensual, status-laden terms like “cool, white,” “beautiful,” and “naked,” augmenting the implied purity and femininity of the mistress’s “soft blush,” her “silk/or taffeta” and her “French perfume.” Duffy’s sentences are lists that catalog details of the speaker’s daydreams like parts of a portrait.

Lorde’s speaker, on the other hand, is disenchanted, releasing frustration and disappointment in short bursts as she grapples with a personal betrayal that has no perpetrator. “Martha Pt. 2,” the more harried and apprehensive of the two poems, is, through its run-on sentences, in the same ceaseless motion as the speaker, who is constantly calming Martha and clarifying things for her. As a result, her relationship with Martha is suggested to be sullied or dying, surrounded by adjectives such as “muddy,” “dirty” and “bitter,” a kind of distorted mirroring of the “Warming Her Pearls” narrator’s nearly delusional romanticization of her mistress.

“Martha Pt. 2” and “Warming Her Pearls” draw two opposing illustrations of thwarted romance and the loss of the self to love. While the former seeks to make sense of the speaker’s struggle to preserve her identity when it is so intertwined with someone else’s, the latter allows the speaker to gleefully sink into her romantic relationship. The effect on the reader is one of deep compassion for the two characters, both of whom are ultimately trapped by their circumstances and denied the love for which they so earnestly beseech their lovers – and thus literally, achingly alone.

Contact Claire Francis at claire97 ‘at’ stanford.edu.