“The Misfits” is one of those screamingly hopeless films that only occurs when the stars magically align. Said stars (Marilyn Monroe, Clark Gable, Montgomery Clift) are all shown on their last legs; within two days after the shoot wrapped up, Clark Gable would suffer a massive heart attack and die within the week; Monroe would die about a year later from a drug overdose; Clift, too, would die in 1966 after a lifetime struggle with substance abuse. Scripted by Arthur Miller (Monroe’s soon-to-be-ex-husband) and directed by John Huston (who spent much of the shoot drunk, asleep or gambling himself into crippling debt), Miller and Huston make a work which traps, in a brief instant, pathetically dying embers. Now, I’m not talking “pathetic” in a pejorative sense; after all, Webster’s tells me “pathetic” not only means “pitifully inferior or inadequate,” but also “having the capacity to move one to compassionate pity”; “marked by sorrow or melancholy”; and just plain “sad.” “The Misfits” is all of these.

Monroe is Roslyn Taber, an ex-stripper filing for divorce, who ends up in Reno, Nevada with four equally lost sad-sacks at the end of their ropes: the aging cowboy Gay Langland (Clark Gable, in his final film role); former World War II flying ace Guido Racanelli (Eli Wallach, “The Good, the Bad & the Ugly”); a has-been rodeo rider (Montgomery Clift); and a lonely divorcee, Roslyn’s only friend (Thelma Ritter of “Rear Window” fame). They strike up a business capturing wild horses.

“The Misfits,” written in the typically obvious, highbrow declamatoriness of Arthur Miller (but the actors escape him), is crazy to watch, namely because it constitutes one of the rare instances where a film’s subtext is the text. Knowing the behind-the-scenes horrors of its making enhances the viewing experience. It is like one long, sleepless journey into darkness. “The Misfits” is just one long howl of misery that gains in desperation the more it rolls on — the slacker, the lonelier.

“The Misfits” comes out at the tail-end of the classic Hollywood era (1961), and it shows. The photographers who drifted on and off the set (Eve Arnold, Bruce Davidson, Henri Cartier-Bresson) showed off Monroe, Clift, Gable in all their un-Glamour, in a starkly honest look that would have been unthinkable in the studios’ heyday. Everyone has the hang-dog look of tiredness. The players (even Eli Wallach, who still glows from his sexed-up turn in Elia Kazan’s “Baby Doll”) are all made to look bloated or grotesque or basically dead. The editing is odd and erratic, but these glitches actually contribute to its depth. At one point, Monroe’s lips go out of sync with her voice. At another, Monroe’s close-up is interrupted by a blurry soft focus. She has none of the leering, near-pornographic dazzle of her 1950s promotional photos. Here, the camera looks as if it were just crying, doing a terrible job at wiping away its tears, overwhelmed by the state of Marilyn.

Monroe’s melancholy is not just some passive by-product of her mental and physical state; it is an intentional actor-driven melancholy, which shows her remarkable skill at rendering the lonely divorcée who goes to Nevada to drink and drift and die. Her spaced-out husk, perking of bust, and nanosecond weird smiles are all consciously worked out; she does this miserable business only in front of men who expect it of her, then relaxes in front of Thelma Ritter, her only friend. Ritter banters with Monroe with liveliness, but the former is soon ejected from the film’s narrative, leaving Monroe to size up these pathetic men by herself.

The Marilyn performance is so brave precisely because, despite the odds, she survives. She trips over her words, but she survives. Her dress slips off her bare shoulder, as she collapses onto a drunk heap of Clark Gable bellowing “GAYLOOORD” while slamming a car over and over again in punk desperation — and still, she survives.

What’s unusual is that the men do not hunger after Monroe in the typical wolf-whistle, ha-ha way of her more famous, earlier work (“Some Like it Hot,” “Seven Year Itch”). Obviously, the men chase after her — but they do so with the energy of someone half-heartedly trying to turn the lights off without climbing out of bed.

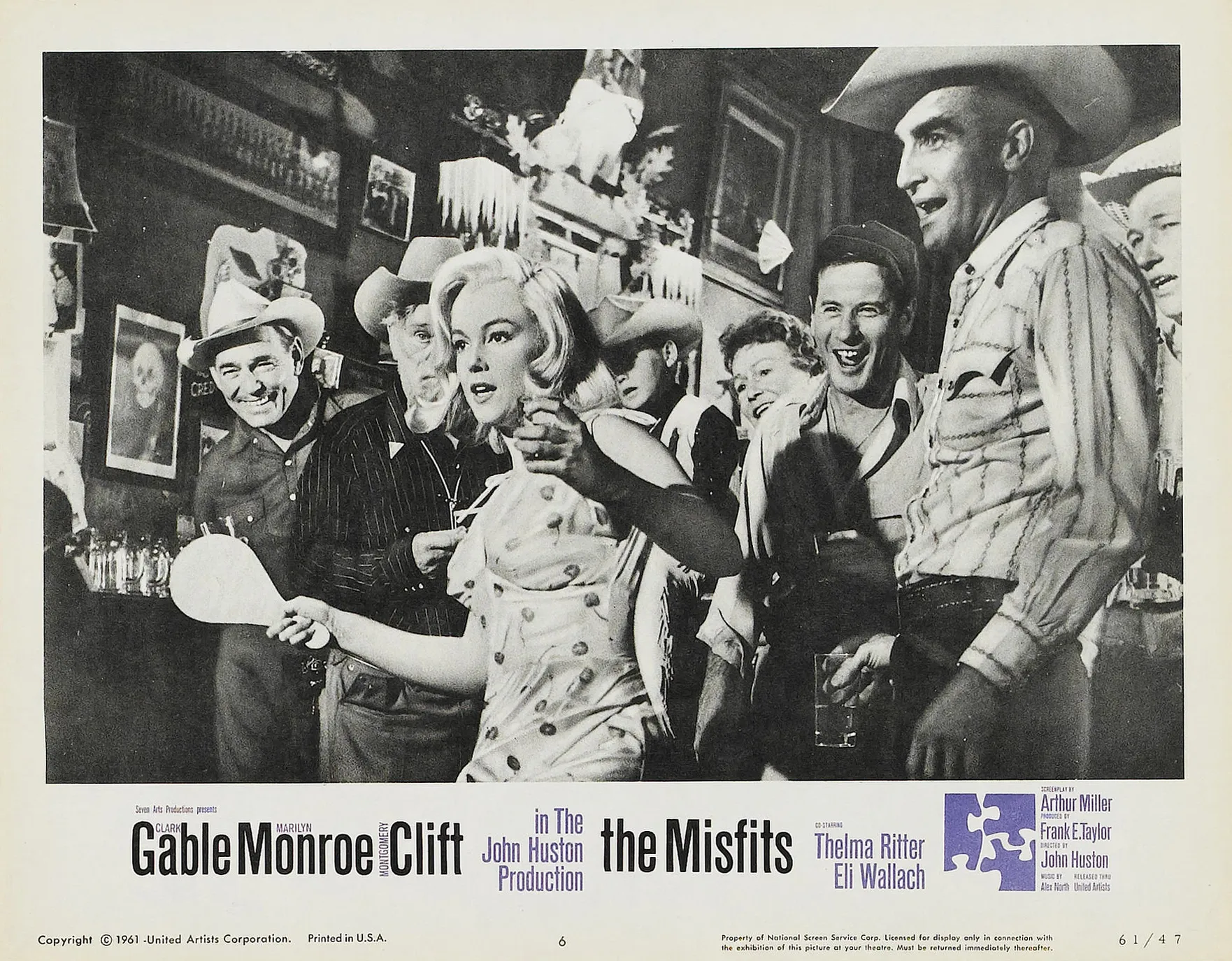

The actors indulge themselves in some grotesque bits of business: Eli Wallach randomly stacks up planks of wood in a drunken early-morning stupor, Gable slams his car until his hand bleeds, Monroe paddle-balls and seduces without being aware of it, Clift confesses to Monroe whilst lying in her lap as if she were his priest, mommy, bae and therapist all rolled into one. Clift is especially a sad case; he doesn’t even seem to be aware there are cameras around him. He is so out of the picture, he is so never in a scene, it becomes painful to keep returning to his gaunt face, his empty eyes.

No actor in the ensemble seems to be aware of the other’s existence. Eli Wallach is a purposeless and disturbed ex-pilot veteran, musing that when he dropped bombs (and maybe the Bomb), he felt nothing: “I can’t make a landing, and I can’t get up to God, neither…help me.” The only person who could possibly change this profound life-hating pessimism is Thelma Ritter, who as usual (c.f., “Rear Window,” “Pickup on South Street”) is the most fun — and who too quickly leaves the picture, just before things get really sad. Otherwise, the “Misfits” ensemble speaks way past each other, never burrowing “inside” the Scene. We don’t see characters interacting with characters; we see stars talking back to stars, confusing their fake life on the page with their real life off the set.

The “action” scenes have none of it; the scenes where Wallach and Gable chase after wild horses have the fun of watching paint dry — and that’s the point. An action-versed and taut director like Howard Hawks would have been disgusted by the utter lack of formal discipline of Huston’s wild-horse sequences, which hang sloppily; just take a look at John Wayne on safari in “Hatari!” (1962) to see how such a scene “should” be done. But to do the scene with Hawksian efficiency would lose the point of this haunting picture, which wants to show (through endless repetition—first a horse, then another horse, then another, then Gable, then Monroe, then another horse, then a truck…) what banality feels like. Huston shows the wild-horse chase for what it is: The last-ditch efforts of failures who whirl around in mad circles in the desert.

Yet behind the dispersive misery, there is exactly one glint of sturdiness, maybe of hope. It is when the men, after all their hard work and physical exertion, decide to shoot the wild horses they just captured, selling their meat for a few lousy hundred bucks. Suddenly, Monroe darts off into the distance and screams at the top of her lungs, “I PITY YOU. I PITY YOU.” Obviously this is not some cheery our-team-wins, guy-gets-the-girl-or-guy moment. But after the knife-twisting anguish of the rest of the picture, Monroe here provides the exact catharsis needed to make us care again about the sanctity of human beings. The camera hangs far back in an extreme long shot, making me feel Rosalyn’s insignificance, and, contrariwise, Monroe’s strength. It’s a rare instance where Rosalyn/Monroe has privacy to herself. Huston wisely does not go in for a typically Hollywood close-up that would show her breakdown and emotional turmoil with dramatic, lurid tastelessness. The camera cannot go in for a close-up. To do so would completely negate the scene’s point: the breaking out of a woman from her banality. She screams: “ENOUGH.”

The dialogue in this remarkable scene (perhaps the climax of Monroe’s acting career) also predicts Monroe’s eventual suspected fate so eerily that it made my skin crawl: “You [men] are only happy when you can see something die. Why don’t you kill yourselves, and be happy?” She could just as well be talking back to Arthur Miller (and the viewing public — us) as she is to Gable, Wallach and Clift. It’s an amazing example of an actor taking back her agency in a narrative that, at first glance, seems to float above the actors. That’s also why its final happy ending is so weirdly successful — because it is so blatantly false, and we know better. As Guido/Wallach observed, we are just aimlessly following the luminescence of stars that are long dead — until the watchers themselves drop dead. Such is the fate of the Misfits, and the fate of those who watch and care for films like “The Misfits.”

Contact Carlos Valladares at cvall96 ‘at’ stanford.edu.