2017 was the year streaming broke pop music. Not in a financial sense – though last year was the first year that on-demand streaming made up a majority of American music consumption – but on some deeper, more fundamental level. Where in prior years streaming felt like an added layer to the picture of the music industry, augmenting but not really determining its core qualities, the pop music of 2017 was undeniably shaped by the peculiar logics of Apple Music and Spotify.

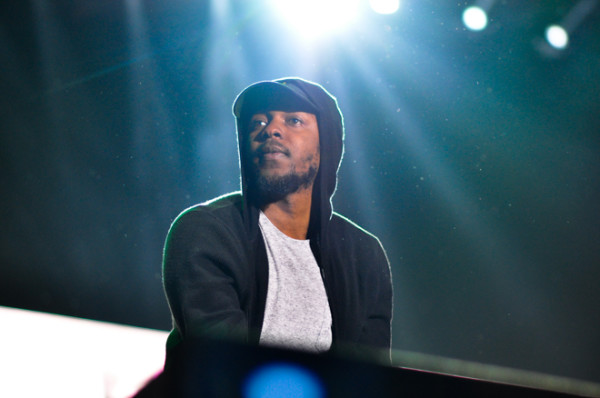

It’s not quite that the old rules of pop music didn’t apply in 2017 – artists still released singles and albums, pop singers still put out baffling collabs with rappers and vice versa – but instead that the relative importance of these rules shifted. The album, in particular, declined as a commercial and organizational force. Aside from a few high profile exceptions (Kendrick Lamar’s “DAMN.,” Jay-Z’s “4:44” and Taylor Swift’s “reputation”), artists eschewed the album as the focus of their work in favor of singles or features.

A number of pop icons managed to remain major parts of the zeitgeist without even releasing or announcing an album this year – Rihanna, Beyoncé and Justin Bieber all notched hit singles this year on features or non album tracks. In the case of the latter two, their guest appearances on songs as diverse as the reggaeton-pop remixes of J Balvin’s “Mi Gente” and Luis Fonsi & Daddy Yankee’s “Despacito,” Bieber’s hook duty on the pop rap indulgence of DJ Khaled’s “I’m the One,” and Beyoncé’s dominance of the duet version of Ed Sheeran’s “Perfect” provided them with more chart success than either of their most recent, critically acclaimed & career reinventing albums. Beyoncé’s “Lemonade” and even her self-titled 2013 album produced no number one hits, but as I write this, the singer’s turn on “Perfect” still remains the number one song in the country. Even an album like Bieber’s “Purpose,” which produced three number-one hits, was outpaced by the “Despacito” remix, which maintained its berth at the top of the charts for longer than any of Bieber’s number ones combined.

Beyond this old guard of established pop stars that maintained relevance without hewing to the traditional album model, a new crop of rising artists achieved success in 2017 without or despite their albums. The obvious example is Cardi B. Despite the “Bodak Yellow” rapper’s omnipresence in pop radio over the back half of the year, her debut studio album doesn’t have a title or release date. A decade ago, such an absence would be clear evidence of label neglect, of an artist left in creative stasis. Now, it’s almost a sign of Cardi’s dominance; three out of her four mainstream follow-up singles since “Bodak Yellow” reached number one in September and have all ensconced themselves in the top 10, and she still has five songs (including “Bodak”) in the top 20. But this trend is also evident in other moves made by artists and labels – Lil Uzi Vert’s “Luv is Rage 2” was delayed due to the massive success of “XO TOUR Llif3,” a soundcloud “loosie,” or non album single, that he dropped in May. This isn’t just idle speculation as to the changing priorities of labels – Atlantic Records executive Michael Kyser said in May with regards to Uzi that “He’s doing 50 million streams a week. Why do I need to put an album out?”

In place of the album, the playlist has arrived as the medium of choice for pop musicians looking for a hit. Playlists like Spotify’s Rap Caviar have become integral to how labels distribute new would-be hits – the curated playlists made by Spotify or Apple Music staffers, or generated algorithmically, represent one of the few ways for new music to reach streaming service users who otherwise might be content to stay within the stable of their preexisting collections. In a way, these playlists have replaced not just the album as a curatorial tool but also the Top 40 radio station as a marketing one. Where an A&R at a record label might have focused on pushing a single to pop stations in major markets in the past, a figure in a similar position now might instead try to get a song onto a Spotify playlist with upwards of five million followers. The importance of the playlist is not lost upon artists, either – Drake, who has always had the canniest commercial instincts of this decade’s pop stars, took pains to refer to his 2017 release, the overly long “More Life,” as a playlist rather than the more conventional designations of album or mixtape.

Yet the weirdness streaming wrought upon pop music in 2017 went beyond just the containers we receive or categorize music in – it seeped into the very sound of the year’s music. The peculiar demands of the streaming market, where listeners have access to nearly every song they could possibly want to listen to, mean that pop writers and producers must try harder to get the attention of a listener to any particular song. In 2017, they did so in two distinct and diametrically opposed ways. The first is to make your song sound completely different from anything else in pop, to offer some escape from the monotony of modern music.

This approach is the approach favored by most of the auteurs of the pop world – think the uncompromising, in-your-face style of Kendrick Lamar’s “HUMBLE.” and “DNA.,” the exquisitely crafted disco pastiches of Calvin Harris’ “Funk Wav Bounces,” or the jarring electro of Taylor Swift’s “Look What You Made Me Do.” Even less established artists came up using this method – soundcloud rappers like Lil Pump and 6ix9ine (who, it should be noted, is terrible and a terrible person) essentially brute-forced their way onto the pop charts with little radio or label support on the strength of unique, meme-able tracks. Not all of these songs were good, but they were distinctive, and they parlayed their distinct charms to the upper reaches of the Billboard charts.

The other approach, and by far the more common one, was to bring your song closer and closer to some ideal of a mid-2010s pop song, to approach pop centrism to the fullest extent. The precise sound of the average pop song is hard to pin down – it’s got a surprisingly diverse range of influences, from the early-2010s EDM-pop of David Guetta, Zedd and Avicii and the milquetoast bombast of Coldplay’s “Viva La Vida” and Mumford & Sons’ catalogue to the hazy, ambiguous style favored by rappers like A$AP Rocky and the cool new wave revivalism championed by performers like HAIM and Sky Ferreira.

It’s perhaps best defined by its lack of definition – it’s not overly dance-y, not hard-edged or too soft. It’s got drops or dramatic instrumental flourishes, but nothing too forceful. It’s never overtly offensive to anyone’s taste, but it never really catches you with a genius hook either – it’s intentionally good background music, able to stock a playlist you put on at a party and then forget about. It’s the sound of Kygo collaborating with Selena-Gomez-collaborating-with-Marshmello-collaborating-with-Florida-Georgia-Line-collaborating-with-the-Chainsmokers-collaborating-with-Halsey-collaborating-with-G-Eazy-collaborating-with-Cardi-B-collaborating-with-Migos-collaborating-with-Katy-Perry-collaborating-with-Nicki-Minaj-collaborating-with-a-Jonas-Brother-collaborating-with-Ty-Dolla-Sign-collaborating-with-Imagine-Dragons-collaborating-with-Kendrick-Lamar-collaborating-with-Maroon-5-collaborating-with-Future-collaborating-with-Taylor-Swift-collaborating-with-Zayn-collaborating-with-Sia. It’s the sound of everything and nothing at once.

It’s the sound of Post Malone. The Dallas musician, who is sort-of-a-rapper and sort-of-a-singer, epitomizes both the commercial possibilities of the streaming age and its stylistic muddling. His debut album “Stoney,” despite debuting to a tepid sixth place on the Billboard 200 albums chart, has sold more than two million copies since its December 2016 release, mostly on the strength of streaming services that don’t really care about when you put out an album. Singles like “Congratulations” and “I Fall Apart” outlived their album’s initial reputation, and occupied prime real estate on hit-making playlists like Spotify’s Rap Caviar and Teen Party lists for much of the year. He was the twelfth most streamed artist on Spotify last year, ahead of figures like Rihanna, Kanye West and Maroon 5.

Beyond whatever machinations may have caused his rise – “rockstar,” the lead single of his sophomore album (which is actually called “Beerbongs and Bentleys,” by the way,) reached number one of the Billboard charts partly due to a fraudulent youtube video of the audio for the song that just looped the chorus – his success in the age of streaming makes sense. He splits the difference between the sound of rap and the sound of pop in 2017 – there’s both the autotune trap-R&B of Future and Migos and the faux-earnest balladry of the Chainsmokers and their ilk in equal parts, with hints of bro-country and classic rock there too. His songs don’t start and stop so much as they drift in and out, almost sleepwalking – perfect material to be slotted indifferently into any playlist for a wide range of genres and vibes. It’s not interesting music, but it’s got interesting enough parts so as not to really be boring either.

But if Post Malone, musical embodiment of bloodless mediocrity, is the best we can hope for as the fruit of pop in the streaming era, then what’s the point? If pop musicians are to keep their relevance in the years to come, they must break from the flattening urge of streaming and create work that’s more than just background music.

Contact Jacob Kuppermann at jkupperm ‘at’ stanford.edu.