In 2018, celebrity heroes are dead.

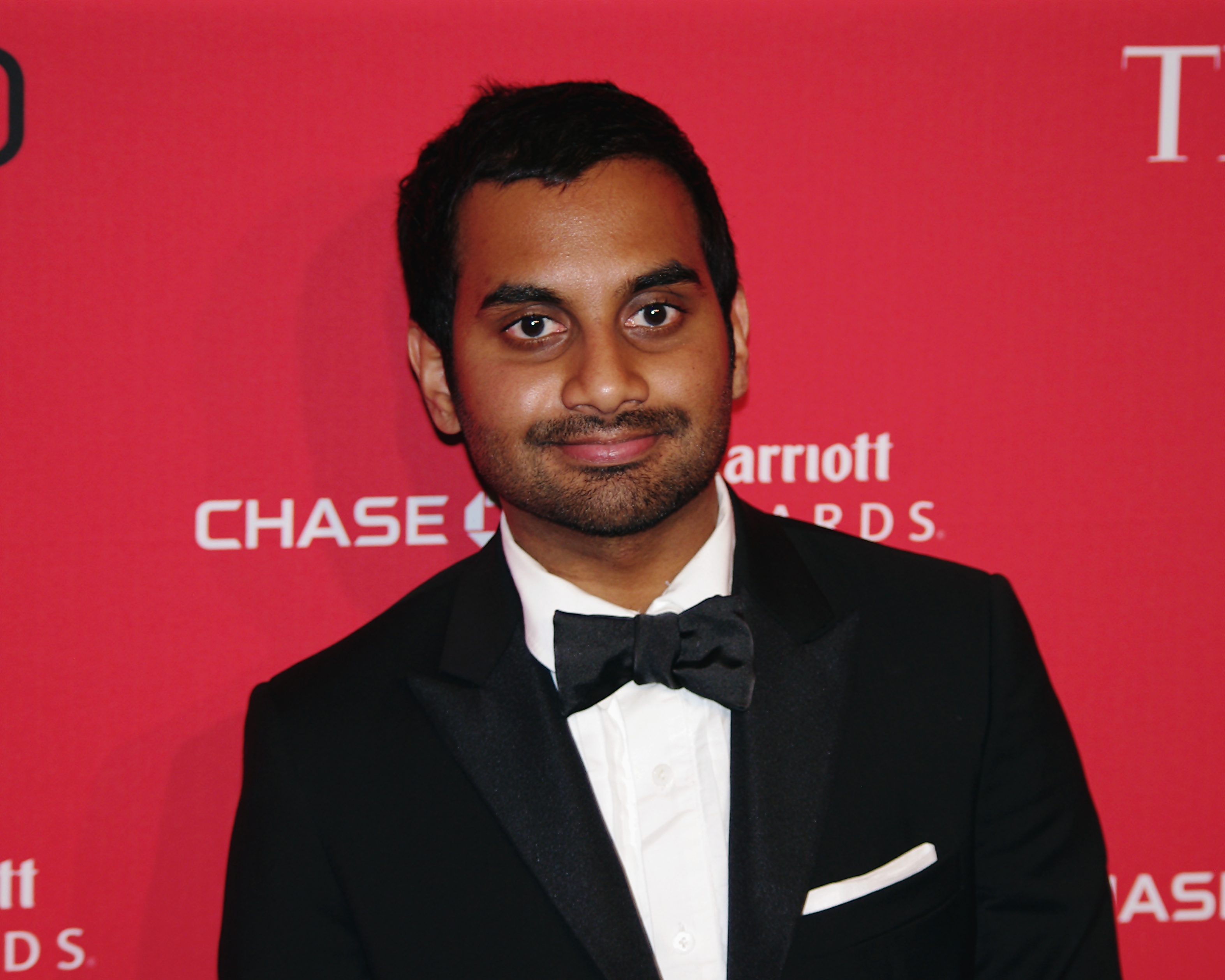

First there was Kevin Spacey, then there was Matt Lauer, Dustin Hoffman, Matt Weiner and, most recently, Aziz Ansari. All were towering figures of art and culture who at one point could credibly stake a claim as one of the greatest in their fields. They were giants.

I was thirteen years old the first time I saw an Aziz Ansari video pop up on my YouTube feed. I can’t even remember what the specific joke was, but I do remember being shocked that there was someone who looked like me that was funny. Actually funny. Not funny because he made vague cultural references to being brown that were stereotypical enough for white people to understand — cough, cough Russell Peters — but funny because he understood the subtle humor inherent to everyday life and told those truths through his own personal lens. Whether discussing religion, women or his family, Aziz Ansari wrote comedy from the perspective of a South Asian American, not comedy about South Asian Americans.

He became my hero.

A hero is a representation of everything we’re too cynical or practical to believe we can possess ourselves. In the media especially, we throw our support behind those individuals whom supposedly practice behaviors or support ideals that we purport to be significant in our view of society. Whether that manifested itself in the nightly news anchors providing calm and support when the world seemed to heavy to continue its orbit, or the actors and producers who brought stories to the screen that touched us in ways we never would have imagined. Heroes are and do the things we never know we needed until we experience them. Heroes are perfect.

Growing up as a mixed-race Muslim American in the suburbs of Ohio, my identity was shaped by forces and people who could never relate to me. South Asians didn’t exist on TV or in movies, there were no required readings on the history of the Ottoman Empire or the great discoveries of the Arab people and the religion of Islam received at most a paragraph in our world history textbooks. As a result, a huge part of my lineage was left to linger in obscurity, solely represented to the masses as Kwik-E-Mart employees and Osama bin-Laden documentaries on the History Channel.

Aziz Ansari was the first time I saw someone like me who was real. He was quirky, intelligent and, above all else, honest. Across his comedy specials and especially in his Netflix show “Master of None,” Ansari refused to deny his own truth in favor of mass appeal. “Master of None” addressed issues of sexuality, generational divides, religion, race — all the little aberrations of society that people face on a daily basis, packaged in a humorous, relatable show that somehow managed to find the universality in a perspective as underrepresented as Ansari’s. Aziz’s alter ego, Dev Shah, was a normal guy trying to make his way in New York City who just so happened to be brown. In a time where every show addressing identity focused on the differences in experience between people of disparate backgrounds, Ansari’s portrayal of normality was revolutionary to me.

Perhaps that should’ve been the first clue — heroes are extraordinary, and Aziz Ansari never pretended to be anything more or less than himself. When the babe.net exposé detailing Ansari’s alleged sexual misconduct broke last week, the story was remarkable to me for its sheer un-remarkability. The victim, “Grace,” details a night that started with great expectations and ended with tears in the back of a Lyft, a night dominated by an awkward, aggressive Ansari who, intentionally or not, ignored sign after sign in a quest to fulfill his own desires, Grace’s wants be damned. The most troubling thing is, it was a night I’d heard recounted countless times before.

Switch an Emmy after party with a high school post-prom “kickback” or a Saturday night on the Row, and you have a tale as old as sexism itself. We can argue over the semantics — is it rape, assault, just misconduct? — but what cannot be denied is that it’s wrong. It’s wrong and all too common.

Which is why what struck me the most about the babe.net article was how Grace’s expectations were based upon an image of Ansari rooted in a fantasy of progressive heroics rather than reality — an image I myself held as well. “I’d seen some of his shows and read excerpts from his book and I was not expecting a bad night at all, much less a violating night and a painful one.” Perhaps Grace had expected to go on a date with Aziz Ansari the sharp comedian, who continually uses his platform to promote feminist ideals. Or maybe Grace thought that she would be dining with Dev Shah, the sensitive, thoughtful New York actor who rails against his predatory TV co-host and always strives to find the perfect romance.

Instead, Grace met Aziz Ansari the man — the inelegant, pushy celebrity looking for sex after the first date, a man whom, despite his token support for feminism, was really no better than the stereotypical asshole “bro” he repeatedly derided in his comedy. Whether that’s criminal or not is fodder for another discussion; what is pertinent here is how our view of celebrity skews our perceptions of reality.

I always wanted Aziz Ansari to be the spokesperson for brown boys everywhere, the spokesperson for me. I wanted him to be our Will Smith or Morgan Freeman — the textbook example of how universal and essential an under heard perspective could be. I wanted Aziz Ansari to be perfect.

But, alas, that desire could never come to pass.

In a time where our president is a former reality TV star and everyday the news sounds more and more like a “Black Mirror” episode, a certain level of cynicism has seemingly snuck into our consciousness. In response, we increasingly look towards entertainment to provide us with the hope and moral guidance once provided by our leaders. In a culture still burdened with deeply entrenched issues of gender, the celebrities that most often rise to the top of the pack are men. We want an unprecedented level of intimacy with those heroes, those celebrities, because we want them to be better than we ourselves ever could. We want them to be the ones who inspire and lead, even if such expectations are always bound to fail. It’s no fault to us — it’s simply a fact of being human. And as humans, sometimes we misjudge those whom we admire, the ones we prop up as our heroes.

In 2018, those heroes are dead. And, ultimately, I believe we are better for it. Some of the greatest mistakes throughout history can be attributed to our faith being placed in men who were never honorable or extraordinary enough to possess it. This moment, the movement of #MeToo, is really our culture is going through a reckoning thousands of years in the making. We are finally beginning to look critically at our supposed icons, and because we have entrusted them as representatives of the values we supposedly want to uphold, we have finally begun to look critically at ourselves. Though the fall of the hero doesn’t necessarily spell the fall of an individual, at the very least we should all work to look a bit harder at how our culture has created and propagated such misdeeds.

For me, that means I’ve had to reevaluate what it means when I say someone is my hero. And what I’ve finally started to understand is that perhaps the whole idea of a hero is itself antiquated. Heroes are for a time when it was okay for men to hide their unsavory actions under the guise of darkness as long as they remained talented and extraordinary in the light. But in the age of social media and information overload no secret can ever remain unburied.

Heroes are supposed to be perfect, and perfection can only be achieved when we choose to ignore the blemishes that afflict us all.

Aziz Ansari is no longer my hero.

In fact, no one is.

Contact Zak Sharif at zsharif ‘at’ stanford.edu.