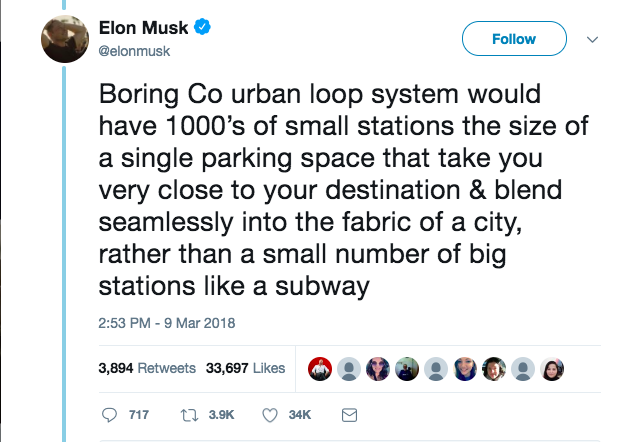

About a month ago, tech mogul Elon Musk came up with what he thought was a brilliant idea:

“[Thousands] of small stations the size of a single parking space that take you very close to your destination [and] blend seamlessly into the fabric of a city,” Musk gushed on Twitter.

The internet very quickly pointed out the problem: These things already exist. In fact, there is a name for them: bus stops.

When this happened, I (and many other urbanism nerds on the internet) had a grand old time mocking ol’ Musky because, well, it was pretty funny. I, for one, made a meme about it that briefly went viral, but that’s not the point. Because when the laughter stopped, we were inevitably reminded of the sobering reality: that one of the world’s most well-known innovators was proud to have spent a significant amount of time to come up with a supposedly exciting new idea, which turned out to be nothing more than a bus stop, one of the most mundane and basic pieces of transportation infrastructure imaginable.

If this were a one-off example, I think it’d be fair for everyone to just laugh it off and move on. But it isn’t. The tech industry, in recent years, has had a series of similar incidents where a company’s “brilliant new idea” turns out to be merely a reinvention of an extremely mundane concept. Elon Musk is not the only one to have reinvented the bus; Lyft, for example, launched a service called “shuttle” that promises “a low fixed fare along convenient routes, with no surprise stops” — literally a bus. Another company came up with the idea of “co-living,” which, if you think about it, is really just another way of saying having a roommate. Another startup, for example, came up with the idea of “[letting] neighbors pool their money to invest in their communities” and did not realize that they’ve simply described taxes.

I can go on listing examples like this for a very long time, and there’s undoubtedly something funny at first about mocking the failures of Silicon Valley. But, after a while, it also becomes clear that there is something that feels inherently ugly about a group of well-off scientists literally reinventing the city bus without realizing it again and again — that these failures are actually emblematic of a larger, more systematic failure of the industry and highlight just how out-of-touch and siloed the tech world has become.

If you think about it, there’s no real reason to expect tech workers to be familiar with a city bus. Simply basing off my experiences with my peers Stanford, many of whom obviously do go on to work in tech, I’m entirely certain that there are plenty of people working for Musk or for Lyft who have never ridden a city bus, either while growing up or as adults today. And why would they have, when they can afford their own cars or be able to travel to work on private luxury buses (the so-called Google buses) that their companies provide?

Instead of fixing things, tech reinvents things, disrupts things and creates new things. And I believe that this irreverent, revolutionary and innovating spirit of Stanford and Silicon Valley is fundamentally good, and the pursuit of that spirit is one of the main reasons that brought me here to Stanford. Yet, with that said, it is also patently absurd to think that all the world’s problems could be solved by starting at ground zero and bypassing the entirety of established traditions and institutions in the name of innovation.

By pretending to operate in a blank slate free of social and historical context and punctuated only by deployment of its so-called innovations, the tech industry absolves itself from social responsibility. The tech industry operates as if under a mandate that makes any and all forms of disruption and innovation of the status quo intrinsically and objectively good — the kind of mandate, for example, that allows the entire industry to cheer on autonomous vehicle technology with not a care in the world that it will threaten the jobs of 4.1 million Americans.

Of course, many existing structures and systems in our society are deeply flawed. Are there problems with public bus services? Of course. Are there things wrong with how taxes are collected and distributed? Of course. But the default reaction to a flawed system cannot simply be to let it die and start right over because, frankly, there is absolutely no guarantee that the new systems would be any better. An app from Silicon Valley will almost certainly not end the millenia-old struggle over what constitutes a fair tax system, a struggle that has taken down regimes and civilizations. Similarly, a bus service from Lyft will almost certainly not make transportation better for the low-income segments of the population that are most reliant on buses to get around.

And that is not to question the motivations of anyone in tech — I am certain that there are plenty of people in tech who work because they want to make the world a better place, and that desire is undeniably good. But, at the same time, utopia is not an Apple 1. It cannot be built from scratch behind the closed doors of a Silicon Valley garage. Reforming and repairing institutions is, without a doubt, frustrating and thankless, which is unfortunately the very antithesis of the shiny, glamorous, instant-gratification ethos of Silicon Valley. And for us at Stanford — the de facto finishing school of Silicon Valley — this understanding is especially relevant. Because ultimately, I know that we do want to make the world better place and not just reinvent the bus again and again.

Contact Terence Zhao at zhaoy ‘at’ stanford.edu