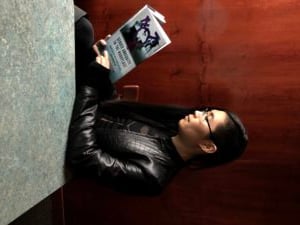

Since graduating last spring, Lily Zheng ’17 M.A. ’18 has worked for the DGen Office and as a diversity consultant. Now, she’s getting ready to publish her first book, coauthored with Alison Ash Fogarty Ph.D. ’15, entitled “Gender Ambiguity in the Workplace: Transgender and Gender-Diverse Discrimination.” The book, which analyzes the struggles that transgender and gender-diverse individuals face in the workplace, draws on interviews with such people.

In conversation with The Daily, Zheng discussed the concept of “doing ambiguity” and offered some words of advice for transgender and gender-diverse people in the workforce.

The Stanford Daily (TSD): Where did the idea to research gender ambiguity in the workplace come from?

Lily Zheng (LZ): This is [Fogarty’s] story more than it is mine. She first got involved in this topic when her friend brought her to a Trans Day of Remembrance 10 years back. She was struck by the impact of the event and really wanted to make the topic of her research trans communities.

TSD: I can’t imagine how difficult it must have been at the start of this in 2008 — finding people who were willing to be open about [their gender identity].

LZ: The landscape of the trans conversation itself, the trans narrative, has completely shifted in that time. 2008 [was] this tipping point of visibility where trans people and trans narratives are beginning to take prominence in media, pop culture, etc. What’s striking to us is that alongside this rise in visibility, we haven’t necessarily seen a rise in the actual outcomes for trans folks. If you look at the data for Trans Day of Remembrance, we’re seeing the number of deaths and killings stay constant, if not rise, over this length of time.

TSD: I think people are starting to formulate an understanding beyond transgender [identities] into gender diversity and gender nonconformity.

LZ: What we’re seeing now is this explosion of gender identities that aren’t just male or female. That’s something that’s always existed — we’ve had gender ambiguity, gender nonconformity, gender diversity — since the beginning of time. This isn’t a new concept.

TSD: Let’s break apart the title of the book. The first part of the title is “gender ambiguity”: What is meant by the concept of doing gender ambiguity?

LZ: In the study of gender, there’s this concept called “doing gender.” It’s this idea that gender isn’t this thing that you passively have — rather this thing that everyone actively does. Gender is a performance. The way you look, the way you act, the way you speak, the way you dress, the way you move — every single thing you do is a doing of gender. You “do” masculinity; you “do” femininity. In the traditional gender canon, there’s not very much discussion past this idea of “doing” masculinity or “doing” femininity. This is something that sociologists just don’t know much about.

TSD: The subtitle of the book is “Transgender and Gender-Diverse Discrimination.” What forms does this discrimination take in the workplace?

LZ: Discrimination happens at all stages in the employment process. It happens even before a person is hired; it happens during the interview — when people walk into the interview, and interviewees will take one look at you and dismiss you. When a trans or gender-diverse person gets hired, then you get a host of micro-aggressions from harassment to verbal abuse to even assault. [In our book,] Rowan’s manager said, “I’m only going to speak up for you three times in this workplace. You have three little tickets to use to get out of discrimination. Are you really sure you want to use one of your tickets now?” This is just blatantly illegal. [Elsewhere,] Robin’s managers retaliated so hard against her for reporting discrimination that they cut her pay from $20,000 in a building to less than $1,000 in that building in the span of one year. […] This discrimination is often so bad that it forces people to leave their workplaces.

TSD: There’s a lot of talk about wage disparity when it comes to gender in a very cisgender, binary sense. But once you go outside the cisgender-and-binary bubble into being inclusive of transgender and gender-diverse employees, then the whole case of wage disparity gets more complicated.

LZ: Taylor and Robin talked about this especially; both of them being trans women, say explicitly, “I made so-and-so amount before I transitioned, and after I transitioned, I’m very clearly making less, even if I’m more experienced.” Taylor has a specific story of when trans people transition — no matter where they are in their job history, no matter how experienced they are — it’s like they start over … When trans folks deal with this gender discrimination, what they’re really dealing with is two kinds of discrimination at once.

TSD: What were some hypotheses that you had during the research process?

LZ: One of my coauthor’s hypotheses was that masculine people will always do better than feminine people in the workplace. What she ended up finding was that it wasn’t necessarily all about whether you’re a man or whether you’re a woman. Rather, it’s about what direction your gender expression and your gender identity are moving along the spectrum … When you have “butch” or masculine-presenting women, they are actually rewarded even though they continue to identify as women. They get benefits because the way that they’re presenting is moving towards this dominant masculinity. Whereas if you see some of the men that we talked to — folks who are moving away from hegemonic masculinity — they get punished for moving away from masculinity.

TSD: I’d imagine you had a pretty wide breadth of demographics among your interviewees — race, presentation, age. Were there any commonalities amongst them, or within subgroups of them?

LZ: All of the people who we talked to had strategies to deal with discrimination. Some of them worked better than some others, so we documented all of these strategies and really looked closely at which ones worked for which people. This is something that I think non-binary people can really speak to, but there’s this idea that you have to pick a gender [to avoid discriminatory treatment]. You have to be a man or a woman. This push toward the gender binary — this absolute insistence on it, really — comes through in the story of Sawyer. When they were getting hired, the person who was hiring them said, “What’s your gender? I need it for the records.” Sawyer said, “Either’s fine,” and the person that they were talking to said, “Absolutely not. You must pick one.”

TSD: What factors make for a more inclusive work environment?

LZ: I would say there are two major factors that we found, and these two are culture and leadership … If you have a workplace that’s not inclusive from the start, you can design all the policy you want, and the workplace will continue to be an exclusive, unwelcoming place. The second factor is that when people are dealing with a change, they look toward their leaders. When leaders, managers, CEOs, etc. are able to buy into this idea [of inclusivity] and to really emulate it, they become role models for the rest of the organization.

TSD: Building off of that, what are some ways for employers to make the workplace more inclusive?

LZ: If you’re a leader, you have an incredible potential to create that culture and create a space where your employees can feel good. And if you’re not in that position, there’s also a really strong role in allies … Everyone has a responsibility, and everyone has an ability to really tangibly shape change.

TSD: Finally, what words of advice do you have for transgender and gender-diverse people in the workforce?

LZ: Do what you need to do to survive. I think something that’s been happening with the new wave of trans visibility is we’ve seen really strong calls for trans people to be out all the time. That really makes me uncomfortable because not all trans people want to, can be or even should be out. Many people are making choices around the safest thing for them right now, or the thing they need most, and oftentimes the need for security and safety is more important than the need for authenticity or visibility.

This transcript has been lightly edited and condensed.

Fogarty and Zheng’s book is out on April 30. There will be a book launch event at Stanford’s d. school on May 21 from 4:30 to 7 p.m.

Contact Jacob Nierenberg at jhn2017 ‘at’ stanford.edu.