In JAPANLNG 100: Reading in Japanese — a one-unit independent reading course that emphasizes academic autonomy through self-studying — each student becomes their own educator. Targeting students already familiar with the language, JAPANLNG 100 uses novels, magazines, periodicals and even manga written in Japanese to push students toward fluency.

The course relies on “tadoku,” a language-learning approach that originated in Japan and emphasizes fluency through reading literature. Tadoku involves perusing a high volume of material in a foreign language without consulting a dictionary. The method compels students to pick up on context clues and colloquialisms.

Japanese Lecturer Momoyo K. Lowdermilk, who designed the course two years ago, expressed her confidence in the tadoku method as a helpful tool in the language-learning process and as a supplement to other formally-taught Japanese courses.

“Every Japanese course has its clear learning objectives, focusing on cultural awareness and communication as crucial language functions,” Lowdermilk wrote in a statement to The Daily. “[The tadoku course] that encourages an immersive and enjoyable reading experience plays an essential role in Japanese language learning and is an important part of [the Japanese program’s] curriculum.”

Jeongeun Park ’18 said she enrolled in the class because she can personally attest to the merits of the tadoku method.

“[Tadoku] is how I learned English as a second language speaker,” Park said.

The course’s individualized nature also affords it flexibility: students with varying levels of proficiency can design a reading load that offers the appropriate level of challenge.

Japanese Lecturer Emi Mukai, who currently teaches the course, said the class aims to provide students of varied levels of proficiency with “the enjoyable and meaningful experience of learning Japanese through reading that targets their own interests and which allows them to progress at their own pace.”

While Stanford’s typical language classes encourage mastery of listening, reading, writing and conversation via traditional teaching methods, the tadoku method posits that learning a language by reading its literature can better enrich a student’s understanding of the language’s idioms and nuances.

“The books become the ‘teachers’ in our place,” said Mukai. “[The teachers’] role is to monitor and support students in the choice of books appropriate to their individual levels.”

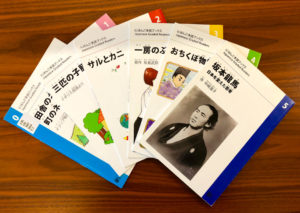

Won Gi Jung ’20, a student enrolled in the class, enjoys the academic freedom the course promotes. Jung said he has observed his fellow classmates reading genres of Japanese literature ranging from picture books to nonfiction historical works to traditional folk tales.

Park, an English and history student, said that an understanding of the Japanese language is crucial to her study of modern East Asian history.

Similarly, Jung, a history major focusing on colonialism in East Asia, elected to enroll in the class to improve his proficiency in the language to better analyze Japanese primary sources. He views documents produced by the Japanese empire during World War II as valuable historical resources that require near-fluency to analyze.

“Reading in [a] foreign language is crucial… to see things from different perspectives,” Jung said. “There are so many texts that are not translated into other languages.”

Learning Japanese is a personal interest of Jung’s.

“As a native Korean speaker, Japanese is easy and fun to learn,” Jung said. “There are many words that sound similar, and it’s really interesting to see how the linguistic properties have been transmitted either to Japan or Korea over the long history of cultural exchange.”

Mukai said that another one of the goals of the course is to instill in students the habit of independent, extracurricular reading for the sake of intellectual growth.

“Language learning requires [a] considerable amount of time and devotion,” Mukai said. “We [in the Japanese department] hope that our reading course will help students to develop greater learner autonomy so that they may continue their learning meaningfully and productively after this course.”

Jung said that he does wish the class had a more rigorous curriculum, which he conceded might be unrealistic to expect from a one-unit course. He also added that more frequent class meetings might better promote the habit of reading in Japanese.

Jung said that the course’s casual nature can sometimes preclude him from challenging himself to self-study.

“Stanford students are self-driven learners, but sometimes, people are too busy and also have really short attention span, as I do,” Jung said.

However, Jung said he thinks Stanford should offer more independent reading courses like JAPANLNG 100.

“Nowadays, it’s really hard for [Stanford students] to really focus on reading when we have so many other assignments to do,” Jung said.

Park echoed this sentiment, and said she has not read much outside of class in her four years at Stanford.

“I believe Stanford can do a better job [of] spreading the campus culture [of] reading,” Jung added.

Sean Chen contributed to this report.

Contact Alex Tsai at aotsai ‘at’ stanford.edu.