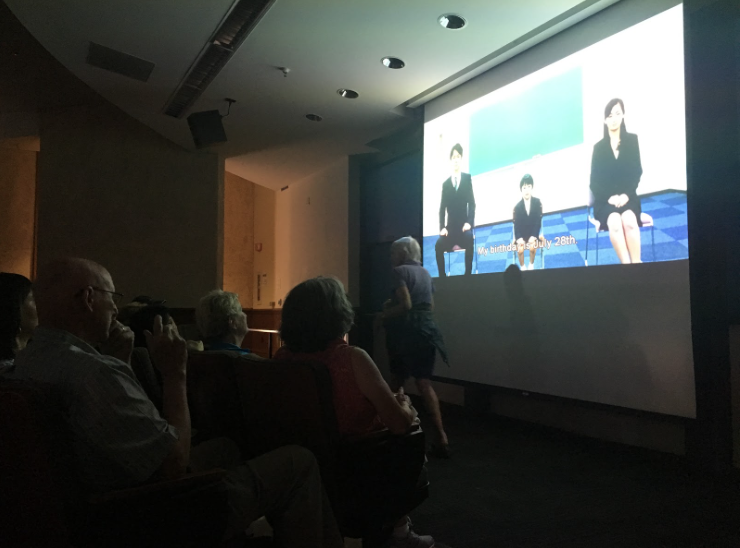

The Japanese film “Like Father, Like Son,” screened in the Geology Corner by the Center for East Asian Studies of the Stanford Global Studies Division (SGS) on July 11. The film was a part of the Stanford Global Studies Film Festival which aims to feature films around the world based on the theme “Friends & Family: Tales From Near and Far.”

Following the screening, Japanese language lecturer Natalia Konstantinovskaia hosted a Q&A session for attendees.

In “Like Father, Like Son,” film director Hirokazu Kore-eda explores what constitutes a family. Through the movie’s narrative arc, he asks whether biological relation is of any significance. The central plot line centers on two families that discover their sons were switched after birth. The sophisticated, upper middle-class Nonomiyas live in a high-rise apartment, a quiet and solemn family atmosphere. In contrast, the Saikis are a clamorous, rowdy bunch — their cramped, dilapidated home is nowhere near as luxurious as the Nonomiyas’ living quarters, but fosters much more laughter and cheeriness.

“The movie raises the question: what makes a good parent, what makes a good mother, a good father?” Konstantinovskaia said during the Q&A following the screening. “Is it to be able to provide that child in a way that would allow him to live in a big house and receive the best education or is it [in] the way that would make you feel loved?’

The film centers around Ryota Nonomiya, a businessman who lingers in the confines of his office and neglects to spend time with his wife and non-biological son, Keita, but ensures he receives the the best possible education. After several meetings with the Saikis, Ryota observes how similar Ryusei Saiki, his biological son, is to him: the natural, assertive leadership and quickness becomes apparent, especially when contrasted with Keita, who is soft-spoken and slow to grasp concepts — but most importantly, his son of six years.

The movie boils down to a central question: is Ryota willing to dismiss his relationship and six years of memories with Keita as a figment of the past, essentially replacing him with Ryusei? And more broadly, in what ratios do bloodline, time and commitment determine family bonds? Ryota asks the Saikis if it possible to truly love someone who is not biologically related.

In the Q&A discussion session, audience members contrasted the Japanese culture portrayed in the movie and American culture. Ryota’s wife, Midori, seems to exist as his complacent shadow — in interactions or discussions with others, Ryota is the sole speaker. Regardless of inner turmoil or disagreement with Ryota’s decisions, she still abides to his word. According to Konstantinovskaia, this dynamic often emerges for Japanese mothers and wives in traditional households.

According to Kelley Cortright, the Center for East Asian Studies’ event and communications coordinator, the Q&A session with the moderator is catered to give the audience a deeper understanding of the part of the world the movie takes place in.

“People who engage with more areas of the world tend to be more open-minded [and] liberal and I mean, not that I want to throw [the word] liberal around because [it’s] speaking in a political sense, but you know what I mean,” Cortright said. “They tend to be more empathetic because they can start to see the world from different points of view. And so that’s really what we’re trying to do.”

During the Q&A, several audience members brought up the logistics of the decision-making itself, asking why no one seemed concerned about the well-being of the two sons themselves. In the movie, decisions were determined amongst the parents, without third-party input.

But in America, Konstantinovskaia said that an external source like a psychologist may have been consulted about the switch.

Several scenes in the movie were especially emotional for the audience members, such as when Ryota informs Keita that the Saikis, his biological family, loves Keita more than his father of six years does. Audience members also noted the emotional bonds that grew between both families and questioned if the overall discussion was focusing too much on the differences in cultures instead of the powerful moments in the movie itself.

“Perhaps when the two wives, when the two mothers embraced, indeed, this I think was a very powerful scene,” audience member Achim Wiedemann said. “And for a touching scene, to see the children separate, wanting to mention, to remember their parents or so was touching but also sometimes a little bit melodramatic.”

Contact Helen at cellochums ‘at’ gmail.com