This is the second installment in Alli Cruz’s new Arts & Life column, New York Minute, discussing her experiences with theater and art while studying with the Stanford in New York program. You can read last week’s column here.

I find it incredibly compelling when a work of art attempts to explain loss because it begs the questions — how can we communicate absence? How do we describe something that is not physically there? I think about this particularly in remembrance, in attempting to explain the life and legacy of a person whom we’ve lost: Is it even possible to describe a human being to another person without turning them into a character, into a sort of mythological presence?

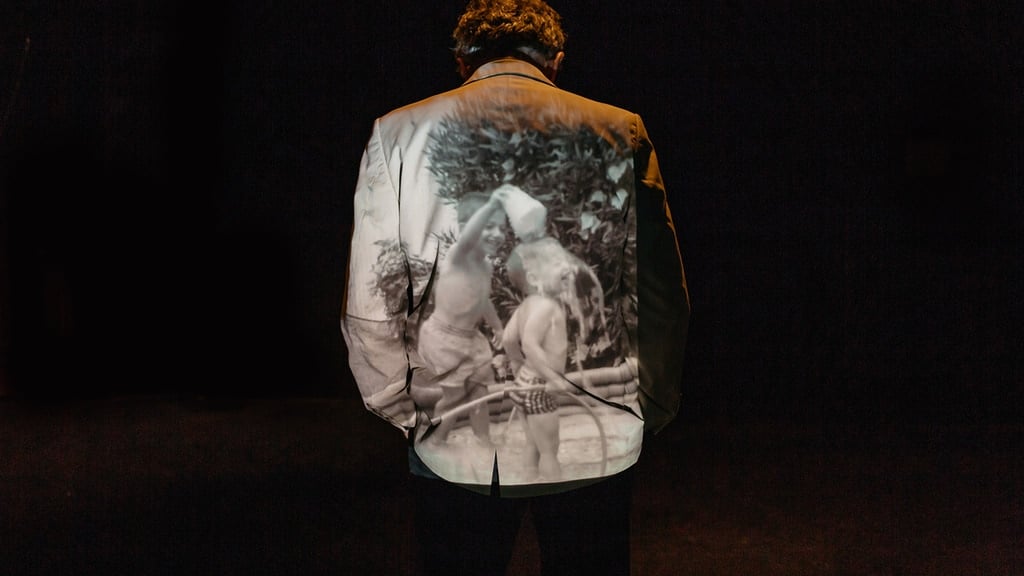

“The Things That Were There” by David Greenspan, which had its world premiere at The Bushwick Starr in Brooklyn on October 10, investigates this almost inexplicable relationship between presence and absence — between having and losing — in a single family dinner party. Except it’s no ordinary dinner party. The play actually occurs in several different points in time — simultaneously.

As we sit down with the married couple Mario and Emily, Emily’s parents May and Calvin, and Mario’s father Lenny, we quickly come to realize how cognizant each character is of their existence, of their ephemerality, within the scope of the show. For instance, throughout the play, each character describes past events in their lives — the things and the people that were there — as well as the events to come: the passing of their loved ones, of major life events and even of their own deaths. These narrations, these realizations, are delivered as direct addresses to the audience, making us all at once aware of the characters’ omniscience and yet their lack of power to determine their exact fate.

Several times within the show, the characters even directly reference the play and the fact that they are written into it. Emily’s character, at one point, reminds us that “one day everyone will be gone, and no one will remember this moment except that someone wrote it down.” This poignancy revolving around the inevitability of loss — that of ourselves and those around us — is incredibly powerful and almost incomprehensible in a way. There are several one-liners like this in the show, one-liners that I personally wanted to scribble down in my notepad so that I wouldn’t forget them.

It is sort of funny, actually, that I so badly wanted to remember these lines about remembrance and the process of forgetting because maybe this speaks to an obvious fact of the human experience: We are so deeply afraid of forgetting and being forgotten. And perhaps the fear of forgetting has more to do with the desire for meaning than the recognition of mortality, which is another interesting concept that Greenspan explores in this play. Greenspan’s characters specifically grapple with the meaning or lack thereof of time and of their own actions. Calvin, at one point, says something to the effect of, “Time means nothing, but what it means I don’t know,” which at first seems altogether confusing, yet perhaps this mirrors the disillusionment and perplexity one experiences throughout the course of their lifetime. As time passes, Calvin and those around him imbue the space with meaning, but in a sense, that meaning means nothing in particular — in the way that all meaning and purpose is self-created and subjective.

I keep using the collective “we” and “our” when describing this play because of the immersive quality of the show. The direct addresses to the audience members, the straightforward recognition of collective humanity in the space, is at times palpable. I would say though that my only issue with the play itself is that it may not be as fully developed as I would like it to be — an issue that has a little more to do with the content (that I felt was missing) than the length of the show (50-ish minutes).

This is not to say that the shows lacks meaningful content, but it is to recognize that the show is in an earlier stage and could perhaps still benefit from additional adjustments. Personally, I would’ve liked to have seen a singular moment in which the ensemble of characters come together with each other and the audience. I felt so enthralled throughout the show, and when it ended, I felt as though I really wanted more in a way that seemed a little unsatisfying. But perhaps the absence of a moment of complete unity was intentional, as life itself may be brief or without absolute closure.

There are certainly moments for each character in which they individually connect to the audience. For example, in one of the most harrowing monologues of the show, Mario, following a point in time after which Emily has died, recounts to his son Dylan in his imaginary crib the time when he grew a lime mandarin orange tree, commenting that “it grew somehow” and “maybe you will taste the fruit too, and if not you, someone. Someone. Someone.”

To me, this repetition of “someone” assigns both anonymity and collective unity among the audience and the actors, and it does so in a way that had me in tears. During this monologue, Cesar J. Rosado, the actor who plays Mario, sits in a chair at the edge of the stage and looks out, his eyes fixed and his eyebrows furrowed in painful remembrance. His performance is haunting in such a visceral manner. The weight of his loss fills the room with a kind of heaviness. The idea of “tasting the fruit” relates directly back to Emily’s absence, the fact that she could not taste the fruit of her own labor, could not see her son grow up. Yet, somehow, both Mario and his son grow and will grow.

Other lines which stood out to me greatly were that of Lenny’s: “I know my son, don’t I?” and “The play changed” (in reference to altered memories/events in the show, i.e. Lenny no longer having had a history with prostitutes because the play decided to change itself). I find these lines particularly interesting for the ways in which they, respectively, emphasize how difficult it is to know and understand another person and how fate, like the hand of a playwright, has the full yet arbitrary capacity to change. It is also worth mentioning that David Greenspan himself plays the character of Lenny, demonstrating his versatility and captivating range of talent.

This play perhaps echoes similar existential sentiments from Thornton Wilder’s “Our Town” and “The Skin of Our Teeth,” as well as the absurdity of Kaufman and Hart’s “The Man Who Came to Dinner,” although I find it to be a very unique and standalone piece in its stylistic delivery, nontraditional nonlinear arrangement and incredibly intimate voice.

In a short interview with dramaturg Jesse Alick of The Public Theater, as shown on The Bushwick Starr’s website, Greenspan cites Wilder as a great influencer, even going so far as to recite Wilder from memory:

“We ourselves shall be loved for awhile and forgotten. But the love will have been enough; all those impulses of love return to the love that made them … There is a land of the living and a land of the dead, and the bridge is love, the only survival, the only meaning.”

Contact Alli Cruz at allicruz ‘at’ stanford.edu.