I could visualize Andy Warhol: sun-bleached hair, dark eyes set in circular glasses and an unsmiling, slightly agape mouth. Growing up in one of the artsiest neighborhoods in Miami, I knew that he was a pop art superstar. On the weekdays after school, if I stopped by the Wynwood Walls or dropped into a gallery, I could see some of his work: gridded, multi-colored screen prints of Campbell’s tomato soup cans. However, until recently, I had not seen much of his work in photography. “Contact Warhol,” the Cantor Arts Center’s new, temporary exhibition, revealed to me that side of his art practice.

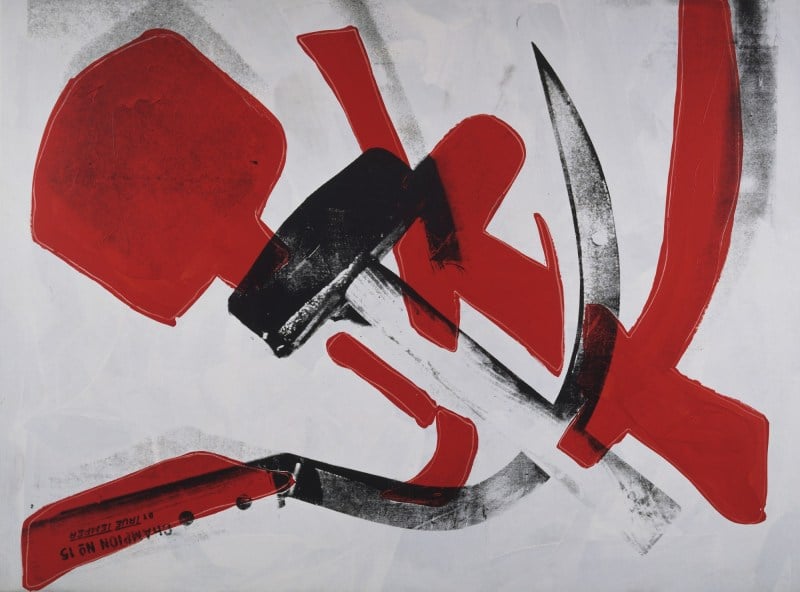

The exhibition, which was curated by Stanford professors Richard Meyer and Peggy Phelan, represents an extensive catalog of 130,000 pieces gifted to the Cantor in 2014 by the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. In the space where the exhibition is installed, the pieces that Meyer and Phelan selected are displayed in various ways: in canvas prints, in video projections and in film strips that line the room. The arrangements of large, vibrant pop art beside small, framed monochromatic pictures gives every wall its own artful composition. For example, there is one wall composed of small black-and-white exposures of a sickle and a sledge hammer; some of the negatives are outlined with red pen to signify Warhol’s preference for them over the unmarked ones. Suspended on that wall is a larger print of one of those same negatives in a modern, wooden frame. The only difference is there is a thick layer of red paint curtaining the sickle and the hammer. The use of color — the crimson pen and paint — contrasts the black and white and also accents the shapes of the items, drawing one’s eyes to the dark curvilinear lines of the sickle and the cylindrical shape of the sledge hammer. All the art in “Contact Warhol” is curated in a similarly visually engaging manner.

Another feature of the exhibition, designed by Amy DiPasquale, is a touchscreen monitor, where visitors can get a zoomed in look at Warhol’s digitized contact sheets. One can also visit the Cantor Collection’s website to access an archive of Warhol’s work and interact with it on their own devices.

In the mid-1970s until the end of his life, Warhol delved into black-and-white photography. “Contact Warhol” consists of the negatives and contact sheets from his practice. The contents of his photos, as seen in the exhibition, are vast. He took pictures of club-goers, buildings, everyday objects like books and tools and so much more. Just from looking, no one can know for certain the technical or conceptual decisions that were made in the capturing of each photo, but we can perceive information about Warhol’s life. The recurring subjects of his photographs — celebrities, queer culture, himself — reveal to us who Warhol spent his time with and what interested him.

In the archive of Warhol’s photographic practice, there are some images that tell a single story, like the one of Jean-Michel Basquiat (a recurring figure in Warhol’s photos). Basquiat has his hands tucked in his jacket pockets and the corners of his mouth folded into a slight smile. This picture gives insight into his friendship with the younger artist. The staginess of these photograph shows how Warhol’s artistic inclination bleed into his everyday life, even the moments when he was simply spending time with friends. He carried his camera everywhere, trying to seize as many moments as he could. Basquiat’s influence on Warhol is also evident. In one work, Warhol overlaid a spotty green pattern atop a black-and-white exposure of Basquiat, evoking the street art style Basquiat is known for and melding it with a Warholian style.

Other images, like a portrait of Liza Minnelli or a snapshot of a Hall and Oates concert, stand alone. Some of the photos are fuzzier and less complete. For example, Warhol took pictures of the outside of the burger joint White Castle and of a gun set on top of a stack of books. These photos, because of their eccentric nature and lack of a human subject, make it difficult to make inferences; all we know about the White Castle is that he went there, and all we know about the books and the gun is that he saw them. We do not — and will probably never — know why he made the artistic decisions he did. For images of his friends, concerts and portraits of celebrities, it is easy to create a narrative. Interviews, records of commissions and other background information might inform our interpretations and understandings (even if our interpretations and understandings are not necessarily accurate to what happened or to what was intended by Warhol).

Still, the photographs can remain enigmatic. The purpose of “Contact Warhol” is not to make its views dream about or contemplate the meaning of Warhol’s photographs. This exhibition aims to give viewers the opportunity to appreciate Warhol’s process as a photographer. The negatives, the pictures chosen for the contact sheets and the markings made by the artist allow us to reflect on his personal approach to photography. We get to view the things that he dreamt about and contemplated and wanted. One of the rare opportunities that this exhibition allows for — and one of the many reasons to visit it — is because we get to see an abundance of Warhol’s work — and not just the pieces he liked most but also the ones that may have never left his camera roll if not for “Contact Warhol.” On the walls of the exhibition above the artwork are famous quotes by him. One of them reads, “An artist is someone who produces things that people don’t need to have.” This is true. When I walked into the exhibition, I entered knowing that I did not need those images forever imbedded in my mind, but after getting insight into Warhol’s life and process, I left there wanting them to be.

If you want to see Contact Warhol, the show is open until Jan. 6. Additionally, there are programs related to the exhibition. To see upcoming events or read more about the exhibition, click here.

Contact Chasity Hale at cah70352 ‘at’ stanford.edu.