Mary Shelley, considered the “mother” of horror, published the first edition of “Frankenstein” in 1818. She has had considerable influence in literary and popular culture, pioneering the combination of the supernatural with science in her writing. In doing so, she laid the groundwork for the current rise of speculative fiction (which I will briefly define as an umbrella term for genres including but not limited to science fiction, fantasy, alternate history, and more). Nevertheless, Shelley was marginalized as a female writer in 19th century Victorian society, and the revised version of “Frankenstein” demonstrates the effects.

When I first read the novel (1831 edition), I didn’t realize that first, there are two different versions (the original 1818 first edition and the 1831 revised third edition), second, the original version was published anonymously and third, the revised edition may have contained Mary Shelley’s name, but it also included edits prompted by public criticism that the novel was too radical for Victorian sensibilities. Granted, the later edition shows the compelling forcefulness of Shelley’s prose after 13 more years of experience, but several scholars argue that the first edition was much closer to her original vision. After reading the 1818 edition, I’m also inclined to agree that this version compared to the 1831 edition has deeper thematic development within a shorter number of pages, though perhaps the 1831 edition has more traditional literary appeal (such as the characters’ greater introspection, a marked improvement).

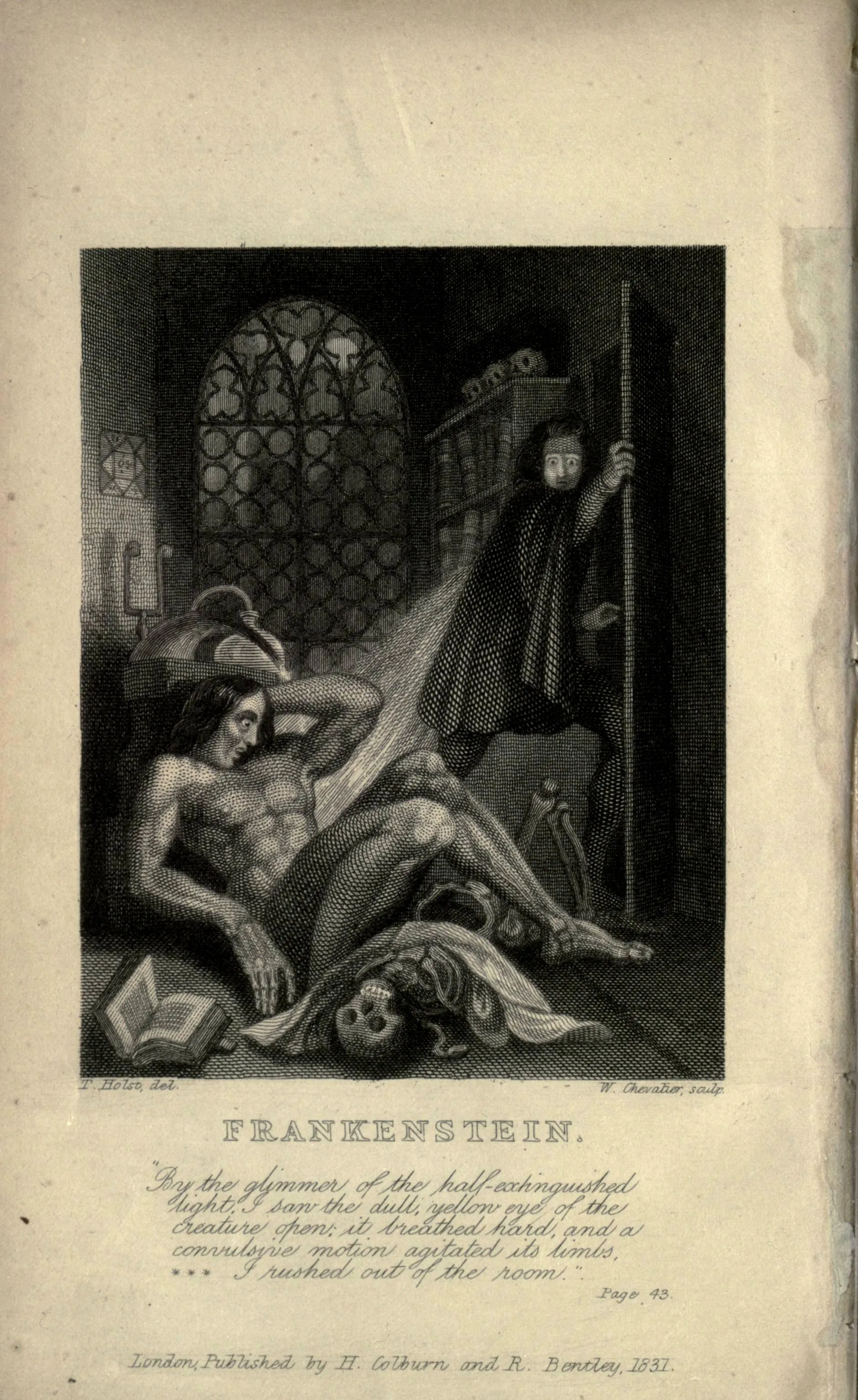

(Note that the title of the novel refers to the obsessive scientist Victor Frankenstein who creates the “Creature” from stitched-together body parts. Dr. Frankenstein, now to be referred to as Victor, was so horrified at its appearance that he ran out of the room and never gave him a name. Hence, Victor’s “Creature” is commonly called the “monster.”)

The first edition (a three-volume novel) was published anonymously, since women writers were not widely accepted by the public. When the second edition in 1823 included Shelley’s name, critics reversed their formerly positive reviews, with a rumor taking flight that her husband, the famous Romantic poet Percy Shelley, was the true author. He did write the preface and helped edit the manuscript, but the story most definitely sprung from her imagination and quill pen. Nevertheless, the 1831 edition was far more popular and is still the more widespread version today, even though Shelley had to make several changes to comply with Victorian mores.

By 1831, Shelley had become a widow and witnessed the deaths of two of her children, so she had a different perspective on the story. Perhaps the most significant change is the shift in emphasis from Victor’s mistake as creating life and then choosing to abandon it, to the act of creating life itself. In the 1818 version, as soon as Victor “sees the dull yellow eye of the creature open,” he rushes away and refuses to return to care for the Creature, restlessly sleeping and then later wandering the streets with his old friend. He then spends several months pretending that the Creature does not exist, effectively abandoning him. When the Creature starts narrating his story, he explains that he first awoke and found himself “desolate” as a “poor, helpless, miserable wretch,” akin to a newborn child who is left to flounder in the wilderness and must learn to walk and speak on his own.

Like a disobedient child (albeit one with far too much physical strength), the Creature eventually becomes overcome with emotion and seeks Victor’s attention through committing his first crime – killing Victor’s younger brother. Though the murder itself is heinous, one could argue that Victor does not teach him any other way: Victor’s faulty parenthood is to blame. As the Creature pronounces, “I was born good… until evil became my guide.” By the end of the novel, the Creature appears much like a Byronic hero, drawing a parallel from himself to Satan in “Paradise Lost” through their tragic spiral towards sin and stoic acceptance of their suffering.

In the revised 1831 edition, Shelley suggests that Victor’s sin was daring to “play God” by creating life. Thus, she removes his crime of intentional neglect by depicting Victor as a victim of destiny. Victor’s own exposure to the sciences comes not at the hands of his father (as was in the original edition), but a stranger who explains how lightning struck a tree near his home. Victor is painted more sympathetically – even admirably – as Shelley stresses how he was left to his own devices as a young boy and had to cobble up his own education in the sciences. His scientific curiosity now springs from a Renaissance search for the Ideal instead of his hubris. Victor now appears heroic for willingly sacrificing his time and health to form the Creature.

In doing so, she strengthens the parallel between Victor’s haphazard education from his parents and Victor’s own faults with teaching the Creature, implying that Victor is only perpetuating the cycle of neglect instead of committing intentional harm. (Of course, the Creature has other opinions. Read more on how this reflects the slave narrative.)

Shelley claims in her introduction to the 1831 edition that she had “changed no part of the story” and only “mended the language,” “leaving the core and substance untouched.” Several changes, such as streamlining several descriptive phrases and adding more reflective passages, improve the novel’s somewhat choppy beginning and deepen Victor’s interiority.

However, where’s Victor’s personal responsibility regarding the creation of the Creature? Why limit our potential indignation? The revisions from the 1818 edition to 1831 edition changes more than the language.

I am wary of analyzing a story in light of the author’s biography (does it deepen or detract from the text?), but I found it particularly striking that in her notes for the 1831 edition, Shelley relinquishes responsibility over “Frankenstein,” which she dubbed a “hideous progeny.” Responding to the bitter question, “How I, then a young girl, came to think of and to dilate upon so very hideous an idea,” Shelley relates it to the influence of Byron, her husband and her literary parents, only daring to claim she transcribed the story from her own dream.

Like her protagonist Victor, Mary Shelley distances herself from her creation, as if she cannot be held accountable for the manifestation of her radical ideas. Much like the Creature, she acts as if she has no place in the world, no name.

Perhaps this leads us to a general dilemma on how even the stories that do get published may not reflect the author’s full artistic vision, especially for marginalized writers. Mary Shelley’s softening of the novel’s more radical elements in the 1831 edition seems to stem from the need to pacify her Victorian audience (as she was fearful of losing custody over her children), rather than a personal change of heart.

I regard the 1818 edition as more groundbreaking because it demonstrates the fullness of Shelley’s original intent, striking into the reader like a knife with a serrated edge. In the 1831 edition, the knife’s cut is still there, it just leaves a less jagged wound. One of the most significant elements of “Frankenstein” and speculative fiction as a whole is how they probe at difficult topics (like the conception of life, parental and creator responsibility) from a framework that diverges from reality. But if a radical story is clouded by vague sensibilities, how can it achieve the same impact?

“Frankenstein” holds much literary and personal significance to me, and I’m always interested in new transformations of this story (including but not limited to a Frankenstein ballet in 2017). Also consider how it has rippled through popular culture with James Whale’s 1931 film (coincidentally released 100 years after the 1831 edition) and even sci-fi giant Arthur C. Clarke’s short story “Dial F for Frankenstein” (which inspired Sir Berners-Lee to create the World Wide Web).

Though there is so much left to say on “Frankenstein,” I’ll end with these last few questions. Shelley’s work, 200 years later, is even more important to contemplate in our modern era with the rise of AI, potentially our new “Creatures.” Will we regard our new technological marvels as “monstrous” or will we approach them with respect? Who will create them? Who will be excluded? And who will write and influence our opinions about them? The future is not so very far away.

Contact Shana Hadi at shanaeh ‘at’ stanford.edu.