Stanford’s regular decision applications were just due last week, and the flurries of eager high schoolers visiting campus are beginning to slow as they hunker down for the excruciating wait for admissions decisions, coming out around April 1.

Like most college students, a big part of me assumed that upon being admitted to my dream school, I would never have to suffer through the painstaking process of a college application ever again. There would be no more campus tours in which I’d be paraded from one building to the next by a peppy junior, double-majoring in mechanical engineering and film studies, walking backwards while he spouted facts about the school that the average student had never even heard of. There would be no more awkward sessions with counselors who told me to look for more “safety schools” and find more eloquent adjectives for how to describe myself like “gregarious” or “affable.” Never again would I put off an ACT practice exam for so long that I’d step into the real thing with zero idea of what sort of questions were coming my way — because never again would I be forced to take an ACT test. More than anything, I was free from having to write exaggerated, self-centered essays about the accomplishments I had so desperately thrown myself into throughout high school.

It was hard work to make the life of an inexperienced teenager seem relevant enough for universities that had helped nourish and cultivate geniuses and heroes, especially through measly blurbs and confusing numbers. When I got my acceptance letter, I was finally free.

Then my younger brother entered his senior year of high school.

Breaks suddenly turned into opportunities for exhausting road trips, stopping at numerous colleges throughout California and attempting to keep it straight which school had the creative studies major and which didn’t, which did early decision and which did early action, which was on the quarter system and which was on the semester system.

I relearned all the quirky facts that had entered and left my ears the first time around, only to lose them once again to an even more intense lack of interest. Information sessions rotted my brain as parents would raise their hands to pose loaded questions that only served to show off their own children rather than signal genuine curiosity: “Does this school have a private gym for Olympic training?” Or “What’s the average SAT score for admitted students, and where does my son fall into that if he has a 1580?” (The highest possible score on the new SAT being 1600.)

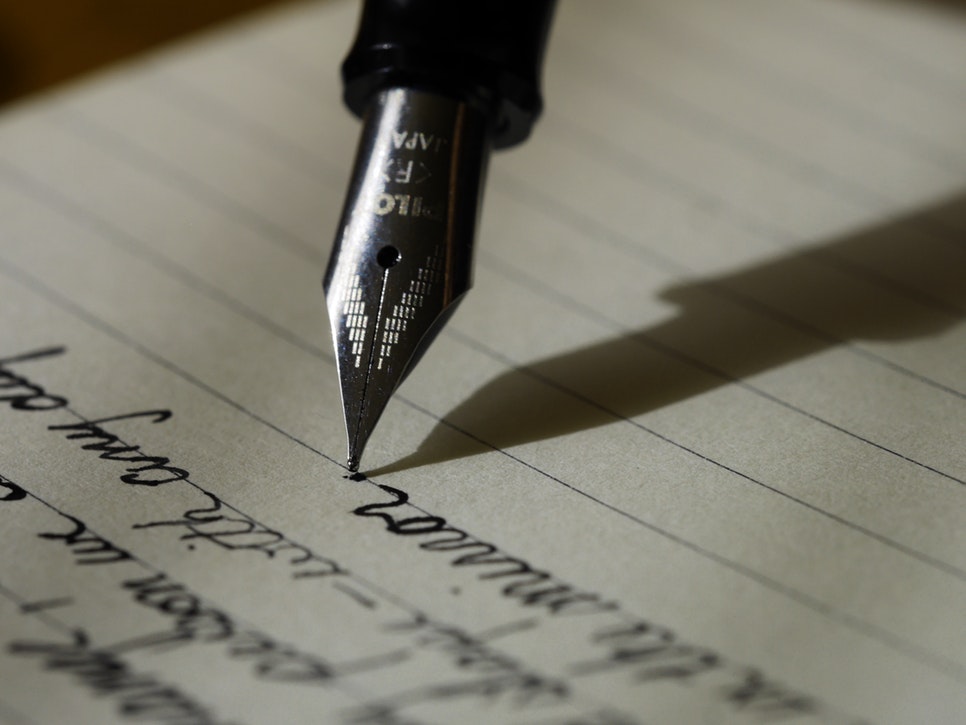

Once again, I witnessed how difficult it was to translate oneself into a piece of paper or a poorly designed webpage, to try and jot down all of one’s best qualities into restricted word-counts and boxes that somehow are supposed to translate into numerical measures of intellectual worth. I remembered what it was like to try and visualize a four-year future in an unfamiliar place based on a couple stops around its campus, punctuated by streams of rehearsed, cringe-worthy puns made by a tour guide that was impossibly cheerful for 9 a.m. on a Saturday.

In the midst of all this reflection on my own previous experiences, I realized how different this process would be for my brother — the sibling that had always been applauded for his happy-go-lucky, laid-back attitude, for his stable sense of calm in even the most stressful of situations. While I dove into all of my research and applications absurdly early, he would undoubtedly wait until the very last minute to even glance at the questions. While I had panicked about each prompt, revising my responses over and over until I could no longer register the meaning of my own words, he would write up first drafts off the top of his head and consider them final products. In many ways, I admired him for this. To watch him power through life without any semblance of pressure or stress was a marvel, and an incredibly impressive one at that.

But eventually, even he began to crack under the pressure. With the application deadlines a few days away, I watched my little brother begin to doubt himself more than ever before; to question if his scores were good enough, to come home from college counseling meetings looking absolutely crestfallen, to recognize that the version of himself on paper could never capture everything that he was and then wonder if everything he was was even enough.

He had his first panic attack while staring at a computer screen that flashed unoriginal prompts on the Common App website. When I tried to help edit his essays or study for the SAT, he ignored me. When my family offered our emotional support, he turned us away.

When I saw him this way, I was conflicted. I recognized the great privilege that the two of us had for even being able to apply to college, let alone to be provided resources to assist us in the process, and I was frustrated with him for not taking advantage of it. But I also felt empathy for him in his self-doubt and his resulting hesitation toward putting himself out there as a list of semi-confident answers. Through this, I identified how easy it was to lose sight of what we were given when we were so desperately searching for the “right” way to be or at least the “right” way to seem.

At Stanford, while I may be done with the college search, there are still constant streams of evaluations of my character, assessments of my worth. There will always be applications to fill out and trials in which to partake that necessitate transforming oneself into a neatly formatted sheet of paper, filled obsessively with ridiculous adjectives and exaggerated descriptions of past accomplishments. I remain forever grateful that my background and upbringing have granted me the chance at these applications at all but simultaneously recognize that all the 150-word paragraphs would never capture all that anyone truly is.

“At least you can apply to college at all,” I remember saying to my brother once when he was acting particularly resistant to my efforts to help him. He flashed a look of anger that quickly dissipated into a deep sadness. “I know,” he said quietly. I left him to work, and when I peered into the room an hour later, he was still hunched in front of his screen typing away as best as he could. The look on his face was no longer one of stress but one of panic, and my heart ached in realizing that my jab at his reluctance only added more pressure. “You’re wonderful,” I told him from the doorway. “From where I stand, any school would be lucky to have you.”

Contact Clara Spars at cspars ‘at’ stanford.edu