At the start of this year, Reads beat writers gathered together to discuss several works that have introduced them to new ways of thinking and being in the world.

Haemin Sunim’s “The Things You Can See Only See When You Slow Down”

Eric Tang, Contributing Writer

I came out of freshman year a mess. I had (and have) all the trademark Stanford anxieties — uncertainty about my career, frustration with my classes, sporadic bouts of loneliness and a gnawing sense that everyone else had it figured out.

Summer was a time to free my mind for a while by inhabiting others’ stories. I read a lot, mostly memoirs. Of those books, the one that best captured who I aspire to be is “The Things You Can See Only See When You Slow Down” by Haemin Sunim. Sunim is a Zen Buddhist teacher, and his work reads like a modern “Tao Te Ching” — in short poems and stories, Sunim offers his thoughts on grief, friendships and self-awareness.

Take, for example, his words on ambition: “The world will keep turning without you. / Let go of the idea that your way is the only way, / that you are the only one who can make it happen.” Or, in another section particularly relevant to Stanford: “My dear young friend, / please don’t feel discouraged / just because you are slightly behind. / Life isn’t a hundred-meter race against your friends, / but a lifelong marathon against yourself.”

Yes, maybe it seems cheap. Maybe it seems like generic 50-cent self-help fluff, inviting the same memes as Rupi Kaur’s poems. But I found some comfort in Sunim’s words — maybe you will, too.

Ken Grimwood’s “Replay”

Katherine Silk, Contributing Writer

Does New Year’s Day ever induce you to reflect on the past year, causing you to wish you could redo parts of it? Are there things you could change, or parts you wish you could relive? If so, perhaps you’d want to be in the same position as Jeff Winston, the main character in Ken Grimwood’s novel “Replay.” Jeff is trapped in a perpetual cycle of replaying his life — and retaining his old memories each time. The book is alternately humorous, exciting and tragic, and the plot takes a fascinating twist when he meets a fellow “replayer” named Pamela. Together, they attempt to find meaning in a life that is extremely transient, wondering whether they can create lasting change in the world. “Replay” explores deep themes without being preachy or didactic and also weaves a compelling tale. I would highly recommend it to time-travel fans and to anyone who enjoys an exciting, thought-provoking story.

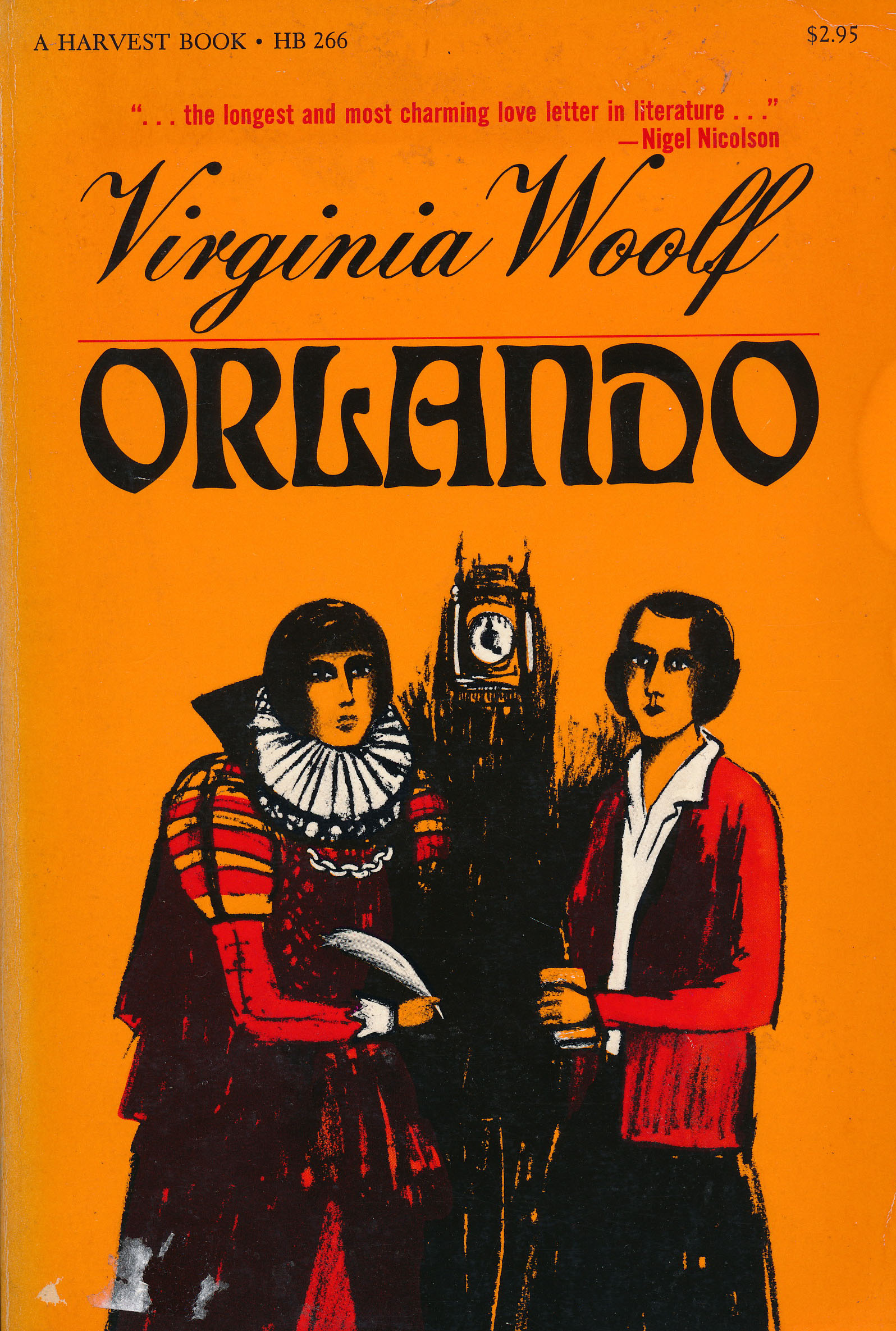

Virginia Woolf’s “Orlando”

Scott Stevens, Staff Writer

What would it be like to live as an Elizabethan nobleman who becomes a woman and remains young until the 1920’s? Virginia Woolf reveals such a life and much more in her fictional “biography” “Orlando,” gamboling along from Orlando’s affair with Queen Elizabeth I, the beginning of his calling as a poet, political hazards in Constantinople and Orlando’s return to England. Later in the novel, Woolf explores the tension between being a woman in the 18th and 19th centuries, but she maintains the adventurous, artistic spirit that carries the main character resilient through the ages. Reading this picaresque, one feels the fun Woolf must have felt bending the rules of genre, gende, and genealogy. At once satirical and generous toward its characters, “Orlando” satisfies the human curiosity to live through history like a rafter fords an endless stream. Though “the present” at which the book ends is 1928, it feels as if “Orlando” has stopped at 2019, with an ending as eternally modern as its titular character. To anybody who doubts new beginnings are always possible, check this book out!

Italo Calvino’s “If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler”

Carly Taylor, Staff Writer

Looking for a new beginning in the new year? Ten beginnings for the price of one single book — this is what you’ll find in Italo Calvino’s novel “If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler.” Looking to be more self-reflective? “If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler” is literally about you, the reader!

How is this possible? Half of its chapters are written in second person, and the other half contain the beginnings of 10 separate novels which you read. Your quest to find the rest of the first novel leads you to all these others. Each of the beginnings you encounter feels vastly distinct, but all are extremely compelling. They will leave you marveling at Calvino’s ability to conjure so many convincing voices and wondering where these stories might lead. Even better yet, you are not alone in your reading in this novel — you find another reader. “If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler” is the perfect book to prompt you to reflect on your personal experience of reading as you read, to see reading as an active experience of creation and to see reading as an act of connecting with others.

Kurt Vonnegut’s “Slaughterhouse Five”

Mark York, Staff Writer

It must be noted, dear reader, that there is only one good way to start off the year, and it is by reading Kurt Vonnegut’s “Slaughterhouse Five.” For what better way to kick-start a new year by doubting whether or not years even MEAN anything anymore?

If this is the first time you have heard of this book, then fret not — it is never too late to change your worldview. No more shall your years be incomplete. No more shall you walk along the street without being aware of an optometrist named Billy Pilgrim and his frapped sense of time. No more shall you hear “aliens” and NOT think of the Tralfamadorians — a race of hyper-intelligent toilet plungers with a hand for a face. No more, dear reader, no more … for “Slaughterhouse Five” is here for your reading pleasure.

I will clarify, in case this had not been made obvious before, that Vonnegut has broken the mold of science fiction and war novels. Though, perhaps that is an understatement — the mold has been scorch-earthed and reverse-big-banged in, somehow, the same instance, and every other instance too (just for the fun of it!).

If Vonnegut ever made an outline for this book, it would resemble less a series of bullets and more the cork board of a conspiracy theorist, for we hardly even spend a whole page in the same time and setting. “Billy Pilgrim has come unstuck in time” apparently … and it shows. We jump from 1963 to 1941 to 1955 without probable cause of reason; it’s nearly nauseating, though in the best way possible, trust me. Throwing aside the realism, the seriousness, and even the linearity that is often found in World War II novels (yet never losing a trace of that impact), Vonnegut creates an experience unmatched by any other.

“Slaughterhouse Five” has my sincerest of recommendations. And if my word is not enough of a call to action (quite frankly, I wouldn’t blame you), then you must live with this: You will never understand the ACTUAL emotional significance of a silent film of a barbershop quartet.

Frederik Pohl’s “Fermi and Frost”

Shana Hadi, Reads Desk Editor

Not to end this listicle on a bleak note, but Pohl’s short story “Fermi and Frost” from 1985 provides an interesting tension to the start of the new year. A powerful evocation of the plausibility of an apocalypse begun by humans, Pohl explores whether we as a species will ever manage to band together before the world ends — and isn’t that the central question for these current times? The story opens with an iconic line, “On Timothy Clary’s ninth birthday he got no cake,” which may first prompt images of a pouting boy laden with presents. That is, until the story expounds on the deaths of his parents, and then plunges into the depths of terror by describing the start of a nuclear war. In this chaos, Pohl sets the scene in an airport packed with refugee bodies and the aura of constant fear. Only by sheer luck does an astronomer receive the chance to flee to Iceland, and, with the stirrings of compassion, he takes Timothy — who was then a stranger — with him.

Though the premise sounds rather terrifying, woven throughout the story are thoughtful reflections on the Fermi paradox (the potential for alien life beyond our galaxy and the contradiction of the lack of evidence … unless they have followed similar self-destructive impulses) and the sheer determination of the remaining humans struggling to survive amidst disastrous odds. Perhaps the most heartwarming moment is when amidst starting a new life in post-apocalyptic, frozen Iceland, the astronomer becomes overcome with the bubblings of happiness when Timothy calls him “Daddy” for the first time. Pohl ends with a ray of hope that pierces the nuclear dust cloud, suggesting that in this story the humans survive by choosing not to squabble and wage war … or as Pohl says, “At least, one would like to think so.” (Perhaps it’s best to reflect upon the story a little more.)

Contact Reads beat desk editor Shana Hadi at shanaeh ‘at’ stanford.edu.