How are we to make sense of composer Philip Glass’s musical minimalism? At his most accessible, his works have found their way into movies like “The Truman Show” and “The Hours.” Yet his more conceptually daring compositions can still appear alienating and intimidating to most audiences. So how should we get to know Glass’s work? Through poetry, obviously. But first: a story to justify my endeavor.

In 1973, Robert Wilson, a playwright collaborating with Glass, was given an audiotape of 13-year-old Christopher Knowles reading a mesmerizingly repetitive poem called “Emily Likes the TV.” Wilson, seeing a hidden organizational logic in this poem, cast Knowles in Glass’s opera “Einstein on the Beach.” Glass must have seen a kindred spirit: He had Knowles write the bulk of the libretto.

We can see why Wilson saw an affinity between the poet and the composer: Christopher Knowles does to the English phrase what Philip Glass does to the musical phrase. Under their care, the phrase is de-familiarized: We cease to understand it the way we are accustomed to, and instead we are presented with fragments that almost make sense. At some point, the fragments cohere once more, either in an eventual reconstruction or a sudden change of context. Finally, we are re-familiarized — led back into the traditional meanings of the phrase.

The ultimate goal of this article is to elucidate Glass’s music, but I’ve always found it a daunting task to explain Glass in words. Glass subverts expectations of musical structure and phrase, but we need some notion of what these expectations are. It is difficult to convey what we expect a musical phrase to mean. Knowles can help us: He works with language phrases, and we all understand what these are. Let us, then, understand Knowles as a path to understanding Glass.

“Emily Likes the TV” begins with a normal(ish) line:

Emily likes the TV because she watches the TV because she likes it.

The next minute or so repeats:

Emily likes the TV, Emily likes the TV because she watches the TV

Emily likes the TV, Emily likes the TV because she watches the TV because she likes it.

Emily likes the TV, Emily likes the TV because she watches the TV

Emily likes the TV, Emily likes the TV because she watches the TV because she likes it.

Emily likes the TV …

After about a minute of this, the words have become alien. We’ve heard them too many times to keep our attention on the meaning — it has become repeating sound. Then, Knowles begins trimming it, From “Emily likes the TV because she watches the TV” to “Emily likes the TV, because” to “Emily likes the TV, be” to “Emily likes the TV” — here we notice the meaning of “Emily likes the TV” again, since we can foresee it’s going to get cut off soon — to “Emily likes the T” to “Emily likes the” to “Emily likes” to “Emily” to a quickly and haltingly repeated “Em-” that gradually settles back into “Emily.” The line then slowly returns in the same manner as it went away. Knowles has transformed the line from coherent meaning to just sound, and then back again. We have been de-familiarized and then re-familiarized.

There’s a comfort when we’ve returned to full line, but we are perhaps still sleep as to its meaning. After all, we’ve heard this line over thirty times now. But then:

Emily likes the TV, Emily likes the TV because she watches the TV because

A: because she watches Bugs Bunny.

An explosion of meaning! With this actual answer, we are hit with the full force of what a TV is, what “Emily” means, and why Emily likes the TV. We are kept here through additional elaborations like “The Flintstones,” “Mickey Mouse,” and “Superman,” before the poem dissolves back into the original line, and ends.

This poem, one of Knowles’ most famous, is a systematic de-familiarization and re-familiarization of a single sentence. It makes sense, and then it stops making sense, and it becomes sound, and from the sound we are reintroduced to a sentence that makes sense once more.

On to Glass, then. We may think of a musical phrase analogously to a language phrase: loosely, some set of notes that has coherence if we intuitively understand the grammar (English grammar, or musical grammar). Just like a “because” will lead us to expect a reason, certain chords (like “dominants”) will lead us to expect other chords (“tonics”). Knowles and Glass repeat phrases until they lose their coherence, or violate the grammar of the phrase, giving us phrase-ish things that we want to make sense but, at best, almost make sense.

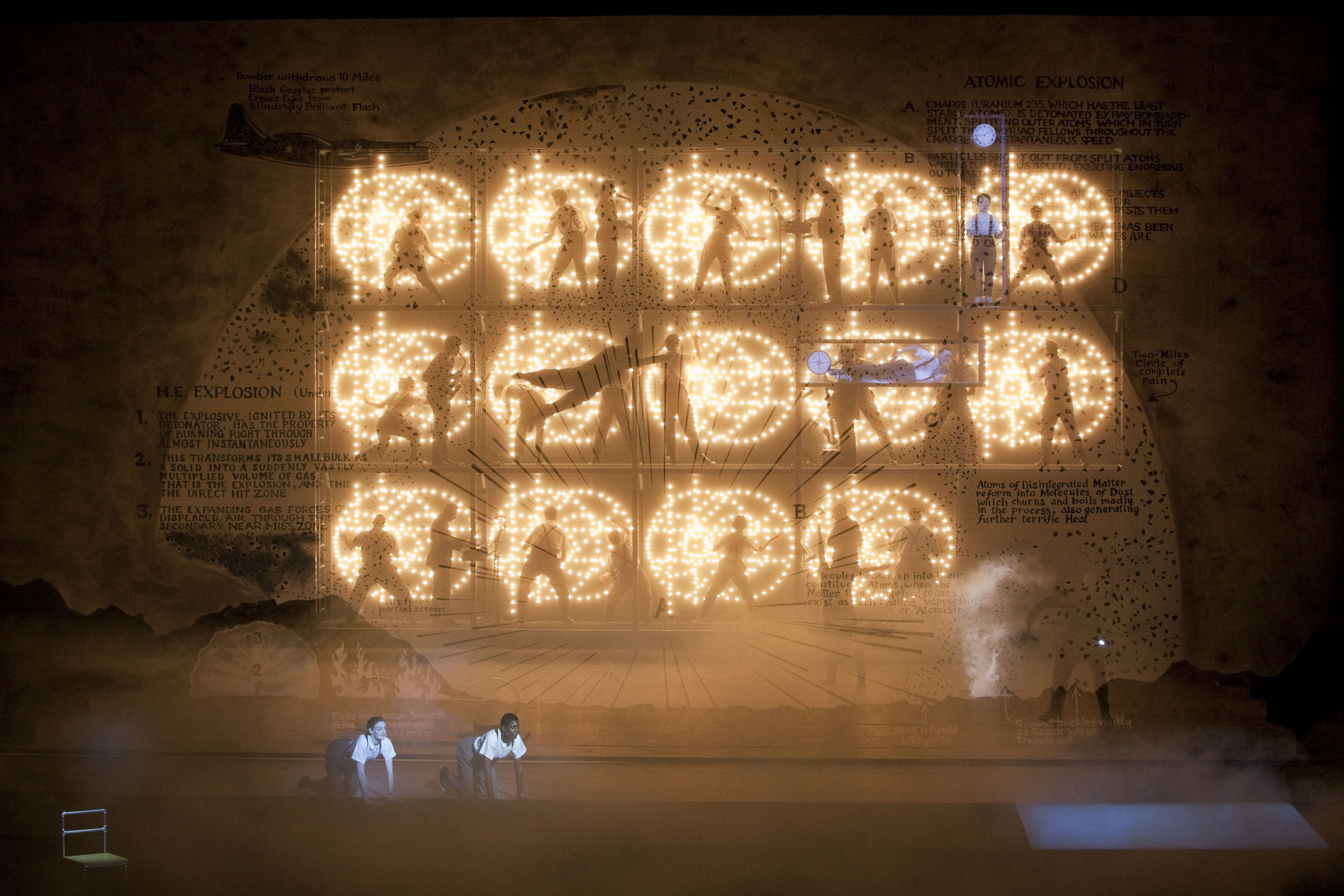

Glass’s “Einstein on the Beach” begins with the following almost-sensical text (by Knowles): “Would it get some wind for the sailboat. And it could get for it is. It could get the railroad for these workers. And it could be were it is …” This comes over a baseline of three repeating chords, sometimes taking four beats, sometimes six, sometimes eight. In one performance, the chord progression begins in the organ as the audience is still filtering in, and the first section, with similar “almost-sense” text over the same baseline, lasts for half an hour.

The three chords, in music-theory parlance, are vi-V-I, a common “cadence” progression, signifying the end of a phrase or section of music. So the opera begins with an ending, and incessantly repeats that ending until the ending no longer sounds like an ending. Our traditional associations with the progression are hammered out by repetition, and the progression becomes just a progression of sound. And then the piece ends, and the vi-V-I chord is suddenly in context. Retroactively, we realize that the last iteration of the chord fits in perfectly with its traditional role at then end of a piece, and its traditional meaning rushes back to us, after the sound has left.

Knowles’ almost-sense text also repeats to the point that we forget that we were trying to make sense of it, inundating us with uncanny grammatical constructions like “Were it is” and “It could Franky” until the question of whether they make sense becomes nonsense itself. What formerly were phrases become fragments of sound, and these are built up into larger scale, more abstract structures — we get a paragraph, but not a paragraph of sentences. At one point, two performers are simultaneously reciting the almost-sense text, and the overlapping sound defeats any attempts to understand what is the meaning of what is being said. The texture of voices thickens and thins, swells and shrinks, but this is a phrase of sounds of words, not of meanings of words.

The de-familiarization present in the works of Glass and Knowles is not the alienation of being presented with something entirely foreign, as much contemporary art has tried to do. It’s rather a more uncanny de-familiarization, wherein something familiar is changed slightly so it no longer makes comfortable sense to us, or it is repeated so much that we tire of understanding its meaning. The two artists take the familiar and de-familiarize it patiently and systematically. It is the poetic and musical expansion on saying a word until it no longer makes sense, or staring at an object until it doesn’t quite seem like an object any more.

The process of de-familiarization and re-familiarization takes extraordinary patience, both on the part of the artist and of the audience. “Einstein on the Beach” lasts four hours, and has scenes of glacial development — like 13 minutes of a performer repeating one stanza of text. But for the audience, the patience required is not one of waiting for something to happen in the music. Rather, it’s the patience of attending to how you begin to perceive the music or the poetry differently as it repeats and repeats, or what happens when you begin to tire of insisting something make sense when it only almost makes sense. Some of the most fascinating and sublime moments of Knowles and of Glass are those moments when a phrase disintegrates out of meaning, or snaps back into meaning, leaving us satisfied, or disoriented, or asking: Did it actually make sense this whole time?

Contact Adrian Liu at adliu ‘at’ stanford.edu.