I first discovered Dave Hickey’s writing during a summer alone in New York. Working at an art association downtown, I spent warm evenings and humid weekends wandering in and out of Lower East Side galleries quietly by myself. For the first time, it felt as if I was in a place where art (with a lowercase “a,” scrappy, but as of yet historically insignificant) was happening and circulating actively through galleries or museums or word of mouth, in front of my eyes instead of on a page or behind a screen. Yet, with all of the novelty and stimulation of this new scene came an equal share of alienation; after all, this was not my coast, nor my city, and most gallery assistants had likely encountered far too many eager young artists to muster any specific warmth towards me. Culture shock should have been no surprise for a then-college sophomore raised in a particularly conservative enclave of central California, but I suppose I couldn’t have anticipated those feelings until I sought to experience them on my own.

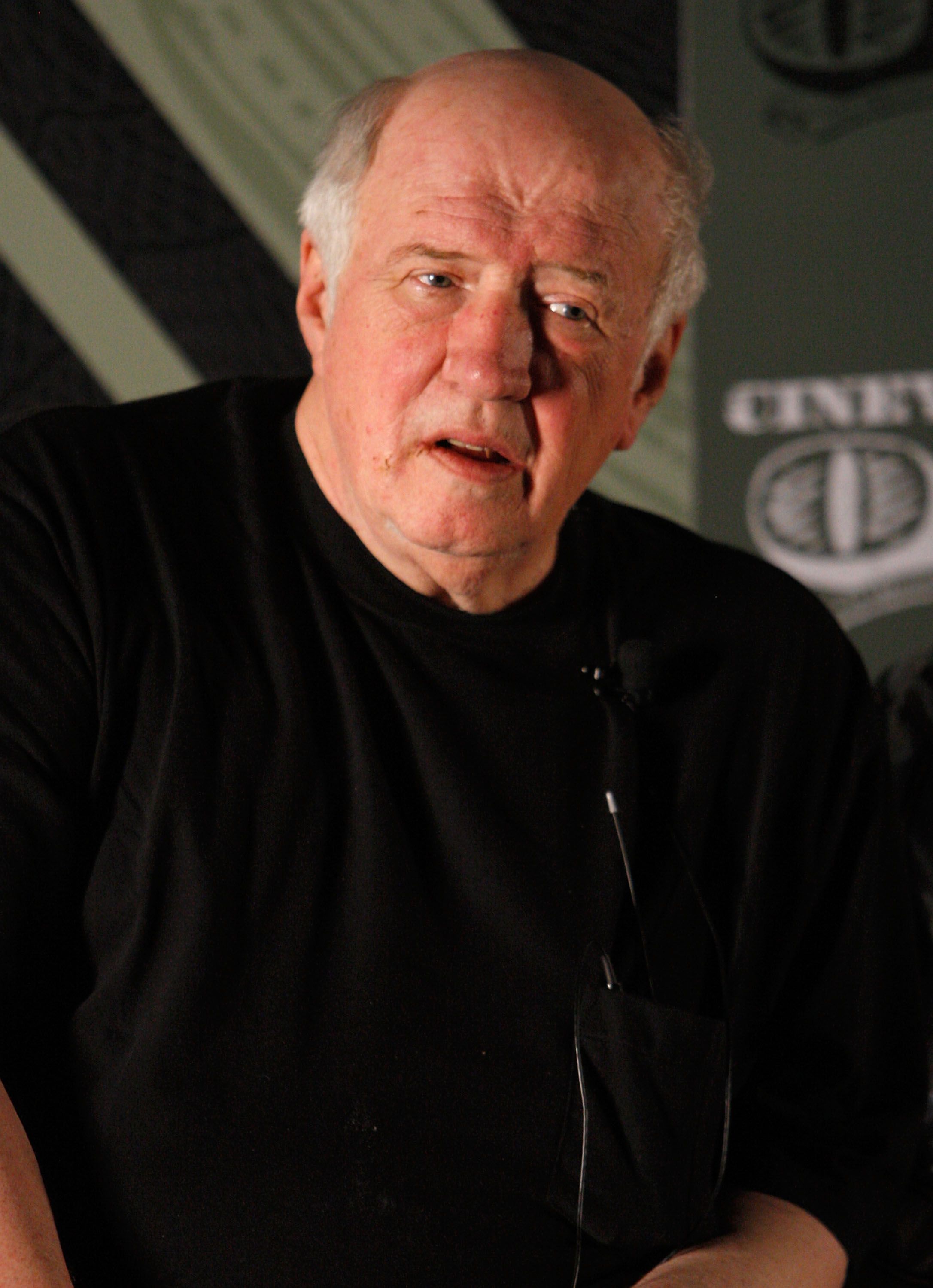

Enter Hickey, the wayward art critic of Las Vegas, by way of a copy of “Pirates and Farmers” bought on a whim from a Chelsea bookstore. I didn’t realize how much I had missed the charming colloquialisms of the southwestern United States until I heard them replicated in Hickey’s jangling, sparkling prose. His work had all of the warm, unpretentious familiarity of home combined with a brilliant and candid matter-of-factness on the subjects of art, music and culture at large. I imagined him as an aging cowboy-wannabe-slash-intellectual who could very well have existed in my own hometown, and even my first time reading him felt like a sort of return. This was profoundly self-affirming during a time in which I had slowly been trained to regret my provincial, un-stylish Bakersfield upbringing in the liberal coastal urban centers of both New York and the Bay Area. Through Hickey, my personal cultural vantage point was suddenly made to feel like an eccentric artistic asset, instead of a shame-inducing handicap.

The rest of my experiences that summer can probably be charted through my obsessive consumption of his writing. I listened solely to Hank Williams for an entire week at work after reading Hickey’s fictional monologue of the lonely cowboy in his wonderfully titled essay, “A Glass Bottomed Cadillac” (included in the collection “Air Guitar”). After finishing his rather infamous “Invisible Dragon,” which served as a useful philosophical consideration of the culture wars of the 1990s, I cut some relatively tame Robert Mapplethorpe reproductions from a discarded auction catalog for the wall of my rented bedroom. My enthusiasm for Hickey was certainly a bit heavy-handed, but it marked what felt like the beginning of my new relationship to art, and to myself.

Hickey’s work is blunt, stubborn and hated as much as it is loved. I imagine that his harsh condemnations of universities and his staunch belief in the democratic capacities of the art market do not make him popular among most academics, and I am not without certain criticisms of his work. That being said, Hickey’s ability to ground fine art in the stakes of everyday existence and popular art/music/etc. in the realm of the deeply philosophical has had an immense impact on the way that I think about my relationship to the world. He is a critic who is well aware of his own subjectivity, and who argues his opinions as if they hold true stakes in his own moral beliefs. More than anything else, he is a writer who has allowed me to believe that I can write about art as myself, and not feel bad about it. From him, I’ve learned that it’s better to be judged for the honest limits of my own subjective experience than it is for replicating the more “acceptable” position of someone else’s beliefs.

Contact Ali Vaughan at avaugha2 ‘at’ stanford.edu.