In celebration of this season of love, Reads writers share some of their favorite works that delve into the human heart and explore the depths of friendship, romance and more.

Audrey Mitchell, Contributing Writer

“The Time Traveller’s Wife” (Audrey Niffenegger)

“Had we but world enough, and time…”

The first time Clare and Henry meet in the Meadow, which will soon become the setting of their hundreds of meetings, Henry is 36 and Clare is six. The second time they meet, a week later, Clare is still six, but this time Henry is 35. After decades of chance meetings throughout time and space, when they finally get married, Clare is 22 and Henry is 30. And 38.

Audrey Niffenegger’s stunning debut novel, “The Time Traveller’s Wife,” follows the defiantly triumphant love story of Henry Detamble and Clare Abshire. Henry is an involuntary time traveler, you see, which means that at any moment he is liable to slip out of time. Therefore, Clare’s and his romance is necessarily a jumbled one, with many of their interactions occurring out of order. Nonetheless, the two of them form a fate-defying bond, existing outside of time even as it seems irrevocably stuck within its bounds, perpetually in fear of the future and unable to escape the past.

The novel explores love and loss of all types, far beyond the scope of a simple love story: from the love between mother and newborn to the loss of an unborn child; from the love of a father for his daughter on her wedding day to the loss of a parent after months of illness; from the elation that comes with young romance to a woman suddenly, utterly bereft of her soulmate.

Rife with Rilke quotes and casual philosophical references, “The Time Traveller’s Wife” transports the reader through time right alongside Henry and Clare through all of their adventures and will strike a chord with anyone who has been far away from a loved one, worrying about them and yearning for their return.

Lily Nilipour, Staff Writer

“Bluets” (Maggie Nelson)

Perhaps when we speak about Valentine’s Day love, we are speaking about love for another person. But we love many things that are not people – our pets, for example, or books, places, even pizza.

Maggie Nelson’s “Bluets” begins as a love letter to the color blue – blue in any form, place, situation or object. Quickly, though, the prose-poetry essay (Nelson famously defies genre categorizations) expands its scope to explore what lies beneath that phrase “I fell in love with a color.” Through a spiraling collection of literary allusions, philosophical tracts and moments in her life, the narrator unveils the spiderweb of love and pain that branches out from its central point of blue. And for the narrator, loving blue often means having to love feelings of loneliness, bitterness and despair. Blue tints her memories of past lovers, and blue dominates in the love between her and her friend, who was severely injured in an accident.

But in its vastness, blue defines not only melancholy but also expansion, light and calm. There is a constancy in the narrator’s love for blue that she recognizes sometimes goes beyond rationality. In asking the question of why we love what we love, Nelson perhaps hints at one of many answers: we’re not sure.

Carly Taylor, Staff Writer

“The Unbearable Lightness of Being” (Milan Kundera)

Kundera’s novel is a book that has everything and nothing to do with love. Though it is the story of a complicated and frequently adulterous love quadrangle, it is also a glimpse into life in Czechoslovakia during the Prague Spring period and perhaps most importantly, it is a philosophical treatise that presents an alternative to Nietzsche’s doctrine of eternal recurrence. Nietzsche’s idea is that we have one lifetime which we live out for an infinite number of times eternally, whereas Kundera proposes in his novel that we live our short lifetime only once. Nietzsche’s framework gives great weight to all our choices, whereas Kundera’s gives our actions a sense of being weightless and arbitrary. Kundera uses each character to present a different approach to this question, and each approach deeply affects how each character views and justifies the role that love plays in their life. The question is, which one do you prefer?

I love this book ultimately because it compellingly illustrates how interconnected love and intimacy can become with our senses of self and reality. It questions whether this relation even makes sense. If you’re alone and feeling introspective this Valentine’s Day, you’ll enjoy this exploration of the deeply individual nature of love.

Scott Stevens, Staff Writer

“In Search of Lost Time” (Marcel Proust)

Spanning over 4200 pages of prose as scrumptious as that tiramisu you imagine your beloved might give you this Thursday, Marcel Proust’s masterpiece “In Search of Lost Time” has taught me much about love (that is, the meager two-sevenths that I’ve read of it). The narrator ambles through his childhood and adolescence, along the way describing the sensations of lime-flower-scented tea, the memories of his mother leaving his bedroom and his first love for the flirtatious, cruel Gilberte. After a rupture in their friendship, the narrator struggles to recover his old self, but he eventually learns the indifference that people must learn to survive a breakup. As the narrator meets other women, Proust captures how love for a person in the past can reverberate forward toward a new person, with unexpected attractions and repulsions from the new lover interacting with those of the old like two sets of ripples in one pond. This is not to say, however, that romance is the book’s only theme. Rather, love for observation of the world pervades Proust’s every sentence. As he tracks the habituation his characters undergo toward their lovers, the “getting used to someone” that happens after about 8 months, Proust demonstrates a rich attention to the many worlds outside and inside our minds. Love is attention; love buffs over what was and what could be. What lies right before our eyes, though, is ripe for tasting, and “In Search of Lost Time” is a manual for learning such feats of attention.

Mark York, Staff Writer

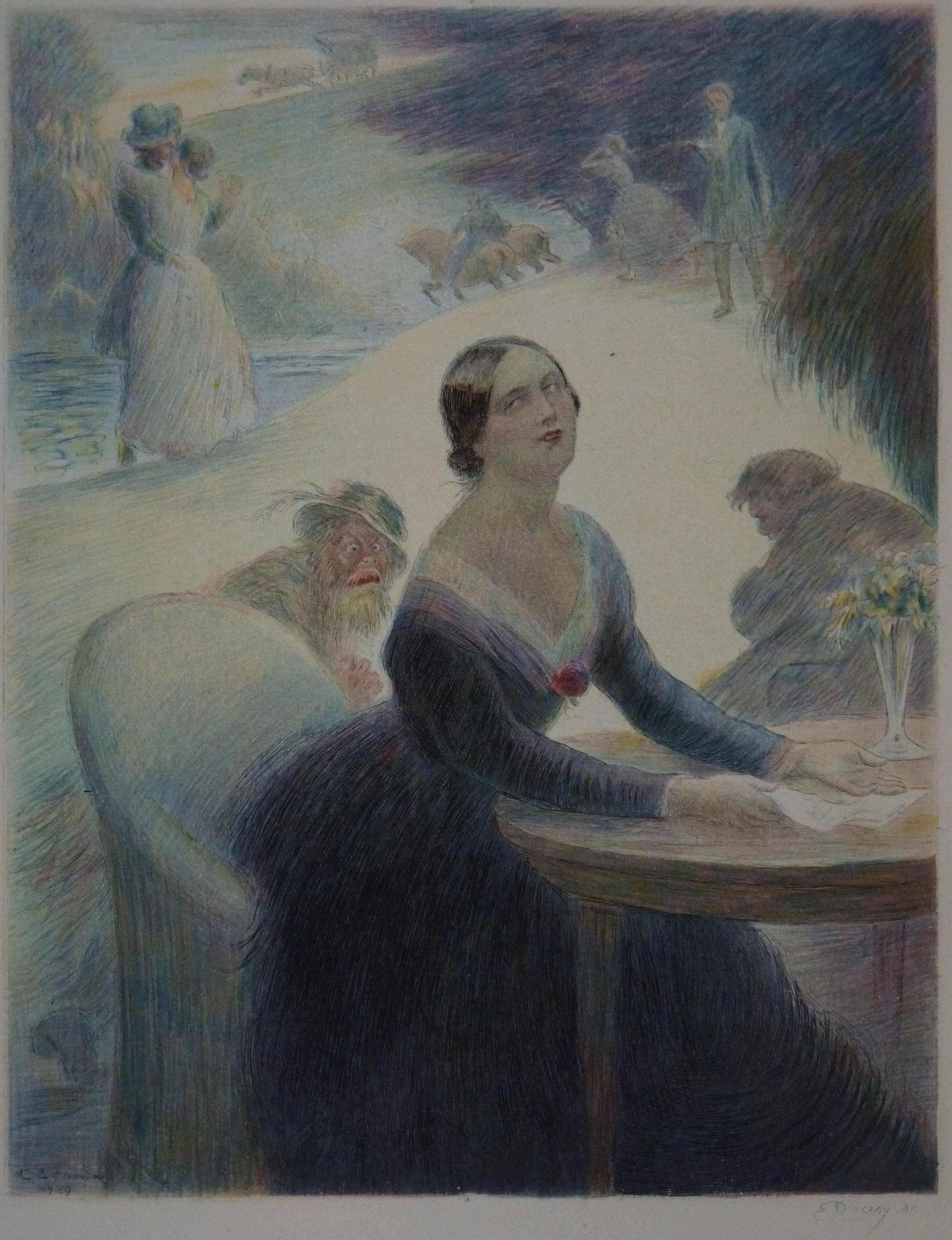

“Madame Bovary” (Gustave Flaubert)

Think back, dear reader, to the epic love stories of written lore. Yes, who can deny the glamor that are Gatsby and Daisy, the tragedy of Romeo and Juliet, the pulls and pushes of Elizabeth and Darcy and the undeniable sexual tension between Santiago and the fish?

I must, however, offer a deviation from this tradition, for I am single, and perhaps a touch bitter. But it is all in the service of a greater good! Just as the shadows emphasize the lights, classic love stories can only be truly appreciated by observing how nightmarish love – or something of that effect – can truly be. And never before have I seen a love story gone so totally wrong as Flaubert’s “Madame Bovary.”

Let us peer into 19th century France, in which a young woman named Emma has recently been married to a guy named Charles. She is constantly disappointed with the world, as a result of her fascination with romantic novels – and it does not help that Charles has the romantic luster of beige paint. Romance comes, however, in the form of steamy affairs… then, it is immediately taken away as they each fall short, providing our protagonist with increasingly negative consequences. Reading this book is akin to watching a cat chase a laser pointer – that is, if said laser pointer also provided the cat with massive existential crises.

As the work is from an older time, it can be easy to dismiss “Madame Bovary” as just another relic of a long-gone era, or just another plain story in desperate need of some cuts. If this is your perspective on the book, then I would urge you to look closer. This is the kind of “love” story in which our couple makes love for the first time during a manure competition. This is the kind of “romance” in which our protagonist’s escapades leads her to massive debt. If you find yourself bitter this Valentines Day, then I guarantee – there is nobody more bitter this time of year than Flaubert.

Claire Francis, Head Copy Editor

“I’d Tell You I Love You, But Then I’d Have to Kill You” (Ally Carter)

Fun, fluffy wish-fulfillment, “I’d Tell You I Love You, But Then I’d Have to Kill You” is the first in Carter’s six-book series set in the universe of the Gallagher Academy for Exceptional Young Women, a snooty, all-girls New England boarding school for privileged teenagers that doubles as a preparatory spy academy. Accompanied by an array of endearing, kickass characters — timid, bookwormish, Liz; ballsy, British Bex; and semi-famous wild child Macey — our 15-year-old protagonist Cammie (codename: “the Chameleon”) is walloped across the cheek by her first proper crush, a boy named Josh from the sleepy Virginia suburb surrounding the school. Girls aren’t allowed to leave the grounds, nor are they welcome to disclose the academy’s secrets to every passing fancy, but Cammie, Liz, Bex and Macey pool their super-spy skills to pull off a string of heists from crafting Cammie’s fake backstory to rummaging through Josh’s trash for reconnaissance. “I’d Tell You I Love You” is a feel-good flashback to teenage puppy love, ultimately ending on a bittersweet note as Cammie realizes that even first loves fade (though perhaps not always as a result of memory-wiping tea). While the plot revolves around the romance, it’s really a secondary element meant to satisfy the narrative inertia as Carter embellishes the rich mythology of the story she’s made — a trend that continues in the next five installments. The next big Buzzfeed quiz: Which Gallagher Girl are you?

Shana Hadi, Reads Desk Editor

“Persuasion” (Jane Austen)

Though madly in love with the penniless young sailor Frederick Wentworth, Anne Elliot allows herself to be persuaded by her family and breaks off their engagement. Angered and hurt, Frederick rushes off to make his fortune on the uncertain seas, and Anne spends the next eight years lost in regret.

When the novel opens, Anne has lost the “first bloom” of her youth. She is close to spinsterhood at age 27, overlooked by her father and sisters and consigned to an idle life in the countryside. However, as a result of her family’s spendthrift ways, they rent their estate to an Admiral and his wife, and Anne crosses paths with Frederick — now a respectable captain in the English Navy — once more. While Frederick offers little in the way of encouragement or its opposite, we can see traces of the former passion that underlies their interactions. Despite foibles and misplaced assumptions, Frederick and Anne steadily move towards each other with undeniable attraction, even when all hope seems to be lost.

Through Austen’s masterful use of free indirect discourse, we enter the rich world of Anne’s interiority, discovering how she has poignantly maintained her love for Frederick with no expectation of returned regard. Immersed in fluid prose that melds with Anne’s internal narration, we experience Anne’s first flutterings of delight at the return of her “bloom” and the unspoken renewal of their courtship. Austen elegantly compresses whole tapestries of meaning into the subtlest of threads, where a stray hand gesture or a chance meeting of the eyes can have a multiplicity of significance. At one point, Anne’s fate rests in the untidy scrawl of a rushed letter — and what this singular object contains will decide the rest of her life.

A seminal classic (and beloved favorite), “Persuasion” offers insight into the constancy of love, as while beauty and wealth may ebb and flow with the seasons, a true, stout love will only grow stronger with the years.

Contact Reads beat desk editor Shana Hadi at shanaeh ‘at’ stanford.edu.