“He and eventually all the other folks who were first responders were able to talk that person away from the edge of the building and from jumping.”

“I recall that incident for a number of reasons,” Associate Dean of Students Alejandro Martinez continued. “But mostly because it was a pretty powerful one.”

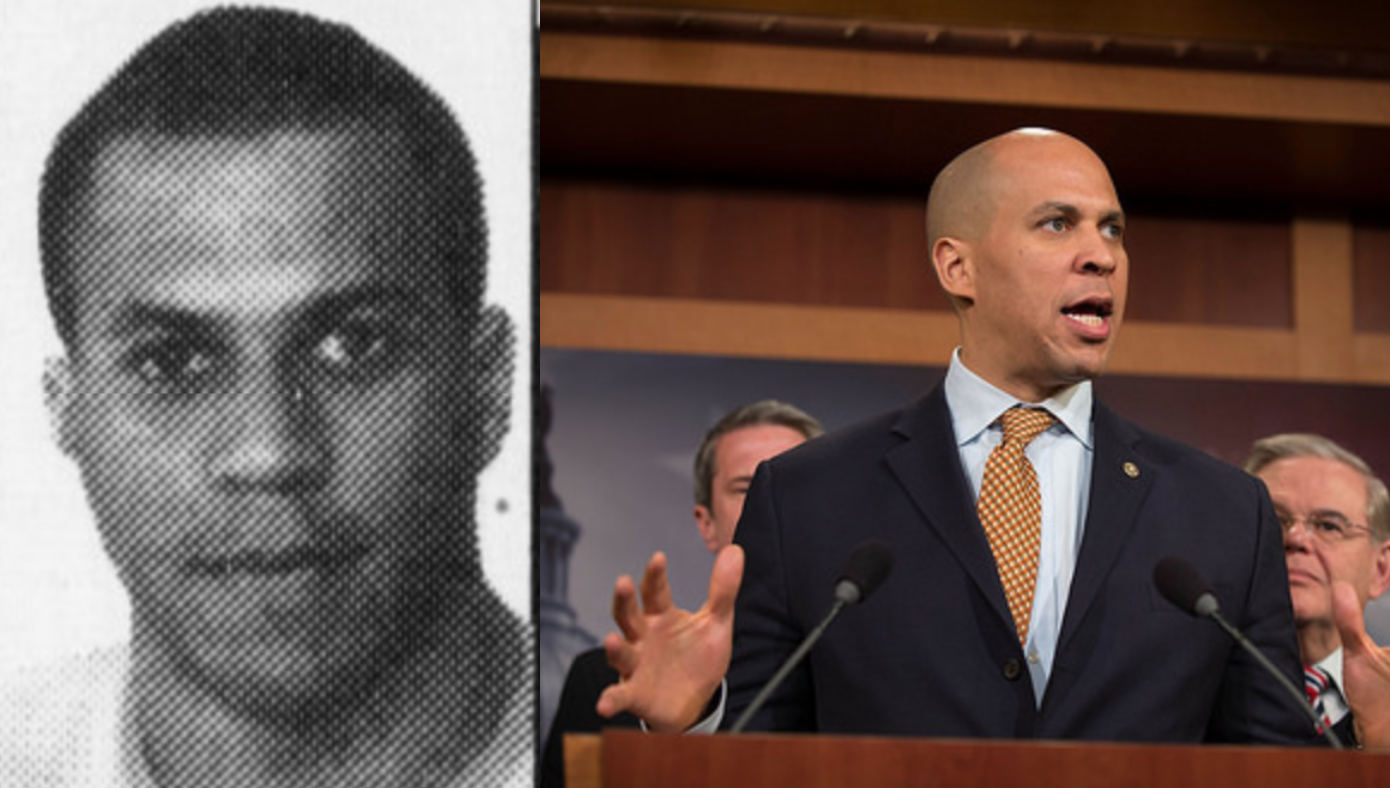

The first individual Martinez referred to was Cory Booker B.A ’91, M.A. ’92, New Jersey senator and 2020 presidential hopeful. Martinez worked as one of his supervisors at The Bridge Peer Counseling Center (The Bridge) while Booker was a student at Stanford.

While he did not have day-to-day interactions with Booker, Booker’s role in helping to talk down a distressed student from suicide marked a moment Martinez said he “will never forget.”

In addition to affiliates of The Bridge, The Daily interviewed Booker’s former football teammates and senior class co-presidents, as well as examined his former Daily columns in order to form a more nuanced picture of his formative college years at Stanford.

Booker did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

‘The backbone of my college career’: Booker at The Bridge

Each school year, The Bridge houses around four trained students as live-in counselors who take turns working night shifts for the 24/7 peer counseling service. Martinez described it as a strenuous job that some students took on in order to “prioritize their experience” around supporting others. Living at The Bridge headquarters in Roger’s House from 1989 to 1990, Booker made such a choice.

“It’s not the dorm life,” Martinez said. “People have to give that up and all those experiences. It is a pretty generous giving on the part of the students to make that commitment.”

When Booker answered a call from a student considering suicide, he immediately reached out to Stanford Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS) and the police before himself going to the student’s location, according to Martinez.

When Martinez arrived at the scene, Booker was standing on the roof of the building, attempting to talk the student away from the edge. He and other first responders were eventually successful.

Booker has talked about this experience on his campaign trail. He has also drawn attention for other choices, including his choice to spend eight years living in a low-income housing project in inner-city Newark.

Some have questioned his genuineness. Martinez said some reporters have even come to The Bridge building trying to verify the account of Booker’s actions that night. To them, Martinez has one thing to say: It happened.

“There was no fantasy story here — it was an actual event,” Martinez said.

Martinez refrained from commenting on Booker’s politics, but vouched for his integrity, at least in his work for The Bridge.

“He was really an engaging person — high energy,” Martinez said. “Friendly. And very committed to the mission, the purpose of the Bridge.”

Booker’s work with The Bridge was extensive, as documented by another Bridge counselor last year. In 1990, he and another student, Jackie Chang ’91, created specialized programs at The Bridge for black and Asian students. Booker led counseling services for black students, with a staff of seven, and described his efforts to diversify The Bridge.

“The Bridge has been viewed as a primarily white organization,” he told The Daily in 1990.

“The Bridge has been the backbone of my college career,” he later told The Daily in a June 14, 1992 profile of him and two other Rhodes Scholars. “It gave me an opportunity to find out things about Stanford that I otherwise wouldn’t have seen.”

‘Carpe Diem’: Booker as senior class president

If Booker clinches the White House in the 2020 presidential election, it will be his second presidency. In the centennial 1990 senior class presidency race, his “Carpe Diem” slate, in which he was joined by David Asch ’91, Elizabeth Lambird Youngblood ’91 and Jacquelyn Yau ’91, beat out six other slates.

As their slate began to form in their junior year, Lambird Youngblood said Booker was suggested as a strong candidate.

“Somebody kept saying, ‘Oh, you should find this guy Cory Booker,’” she recalled.

She and Asch remembered him as a natural co-president and a student committed to service. Asch had known Booker as a tight end, having watched him from the stands of football games. When he met Booker in person, Asch said he was struck by his commitment to The Bridge.

“He was very devoted,” Asch said. “If you’re working at The Bridge, you’re all in.”

Asch described him as “every bit as impressive as what you read about.”

When Lambird Youngblood went to meet Booker at the Bridge, they “hit it off.” Well-regarded for his role there and his athletic ability, she said, Booker made a strong co-presidential candidate.

“He was super affable and industrious and charming and well-liked by a wide swath of people,” she said. “Athletes loved him, and he also just had already begun a whole history of service.”

In addition to The Bridge, Booker also worked for the East Palo Alto Community Law Project, a clinic providing legal services. In his senior year, he was awarded the Dean’s Service Award for community service.

The co-presidents remembered serving their tenure by organizing events for their class — including pub nights — putting together a class gift and compiling a time capsule. They also spoke at Class Day, an event before commencement.

“Cory, the minute he stood up to speak, I mean the crowd already went wild,” Lambird Youngblood said. “It was like he was already rock star at that point — people were on their feet clapping and cheering. It was pretty funny to be in his presence because I was just a random student.”

As a public figure now, Asch said, Booker seems to him “passionate” and “genuine.”

“I would echo those sentiments as far back as you know when we were 20- and 21-year-old kids getting out of school,” he added.

For Lambird Youngblood, Booker now seems “a little bit more hardened, a little bit more streetwise.” In more recent press, she said, she sees “a more fiery side” of Booker.

“When I knew him he didn’t seem to have an aggressive side. And he didn’t seem to be quick to anger,” she said. “I’ve seen a lot more of that, lately, over the last couple of years in press clipping. That’s not a side that I ever saw.”

“We never needed to be,” Lambird Youngblood added. “It was like, ‘Okay, what are we going to do?’ We did some, what do you call it? It’s not a pub crawl. But where you go from bar to bar to bar in the city, and we had to plan that. It’s not like there was a lot of debate.”

‘What’s that?’: Booker the Rhodes Scholar

Lambird Youngblood said she pushed him to apply for the Rhodes scholarship, the highly selective annual scholarship that sends a mere 32 Americans to study at Oxford.

“I told him one time, ‘Cory, you should apply for this Rhodes scholarship thing,’” Lambird Youngblood said. “He goes, ‘What’s that?’”

“I said, ‘Look, you’re African-American, athlete, student leader with The Bridge behind you,’” she said. “‘Like, you’ve got the package’ — and he was also doing his senior thesis on MLK.”

In a 1992 article “On the Rhodes to Success” profiling Booker and two other Stanford Rhodes scholar winners, Booker connected his success to football.

“Football enabled me to get a Rhodes scholarship,” he told The Daily. “It gave me the discipline.”

He also expressed excitement at the prospect of international travel and broadening his horizon.

“I really have a very Americana perspective,” he said.

Booker, who earned a J.D. from Yale in 1997, said he hoped to go to law school.

“I’m no genius,” he said. “I’ll never claim to be a genius. The most important thing I can do with my education is to apply it. I’ll never be a Nobel laureate physicist. I just want to take my degree and help people.”

‘A tough-nose tight end’: Booker the football player

Former football teammates remember Booker, an All-American recruited athlete, as a committed and an ambitious teammate.

“He was trying to win a spot, to play a lot more,” remembered Dave Garnett ’93, another former member of the football team. “And he did play quite a bit actually. But he was a tough-nose tight end.”

Garnett described him as “very smart — as most guys are there — but he was probably even a little bit smarter than most because of his other ambition.”

When Booker won a Rhodes Scholarship, he said, it was an exciting moment for the team.

“It was pretty exciting to know someone who was going down that path,” he said.

Garnett recalled that Booker was “very conscious” around salient issues of the time, including those surrounding race.

“Whenever I hear about him, I think about his smile,” Garnett added. “Even on the football field his demeanor was always the one that was positive.”

The Booker he sees as a public figure now is the same one from before.

“He definitely, you know, acts like nothing is new in terms of where his political stance is where his status is, all that stuff.”

In a 1990 Daily profile, Booker connected his football successes to his faith.

“I owe all my abilities and successes to God,” Booker said. “My faith has been very important to me and has helped everything fall into place for me this year.”

“My faith kept me going and revealed my inner strengths to me when times were tough,” he added. “People say that football builds character, but I would disagree. Football reveals character, and with God’s help, football has helped me realize who I am.”

He also expressed interest in playing football professionally.

“I would definitely like to go pro — for the experience and the money,” he said at the time. “The NFL starting salary would go a long way towards Stanford Law School tuition.”

J.J. Lasley ’93, who played football with Booker and was a year below him, said that although Booker was a “smart” player who other team members looked to for answers, the fact that he didn’t make it to the NFL “did not surprise” him.

“We were on the offense together and we were both ‘football intellectuals,’” he said.

Lasley also described the banter they shared.

“Every girl that he ever saw me with he’d be like ‘Hey, she got a sister?’” he recalled.

Lasley also noted Booker’s diverse extracurriculars, which extended beyond the football team and The Bridge. Booker also wrote columns in The Daily and contributed to Stanford’s radio station, KZSU — “You don’t see football players down underneath the radio station,” Lasley quipped.

“People look at us and think, ‘Oh, he’s an athlete and he’s black,” Lasley said. “They put you into that clique, and then they think everything that black athletes do, that’s what you do.”

Booker and Lasley, talked together about race and belonging on campus. They discussed in detail the 1991 Rodney King trials, in which four Los Angeles police officers were acquitted of charges of use of excessive force after brutally beating an unarmed King, sparked nationwide civil rights protests.

In the context of these protests and riots, Lasley described a shared struggle with being accepted by both the black community at Stanford and other groups between him and Booker.

“There was some ignorant people at Stanford, who had a silver spoon in their mouth who didn’t understand this,” Lasley said. “And they would quip at us and say, ‘Well, you guys don’t have a problem, you’re almost as white as me.’”

For Lasley and other students of color, the Rodney King trials brought issues of police brutality to the forefront, spurring conversations about institutional racism, which is something that Booker is now focusing on in his 2020 campaign.

After George Holliday released footage of King’s brutal assault by police, Lasley said he and other members of the black community hopeful that it was the “beginning of the end of this kind of stuff.”

“We, as a collective, thought, ‘Well, now it’s on film, people will finally believe us,’” Lasley said. “And what was that, 1991?”

“In actuality, it just never stopped, and in fact I think in the last two years since this new president has nothing but increased,” he added.

Lasley said he has a message for Booker.

“I would like to sit down with him again and have another conversation and say ‘God, things really didn’t change, they almost got worse,’” Lasley added.

Booker wrote about the sense of belonging he gained from Stanford’s black community in a 1992 Daily column titled “This one ain’t a sermon.”

“I was imbued with self-esteem and self-concept, without which I would be lost in mediocrity,” Booker wrote. “But most importantly I found a home, in the truest sense of the word, a place where I can go and feel an unabashed sense of love, strength and community.”

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that Cory Booker is mixed race. The Daily regrets this error.

Contact Charlie Curnin at ccurnin ‘at’ stanford.edu and Ellie Bowen at ebowen ‘at’ stanford.edu.