The Global Digital Policy Incubator (GDPi), housed within Stanford’s Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law (CDDRL), hosted its second annual Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HCAI) conference on Tuesday. The day-long event, which is not affiliated with the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI (HAI), spanned issues ranging from tackling the ways in which technology can be used to advance global good to addressing the harmful uses of artificial intelligence (AI).

Human rights, AI and the private sector

To address the responsible uses of AI in the advancement of global good, companies including Salesforce, Microsoft, Google and Facebook presented the work they have done to protect human rights in AI use in one of the events, titled, “Human Rights by Design: Private Sector Responsibilities.”

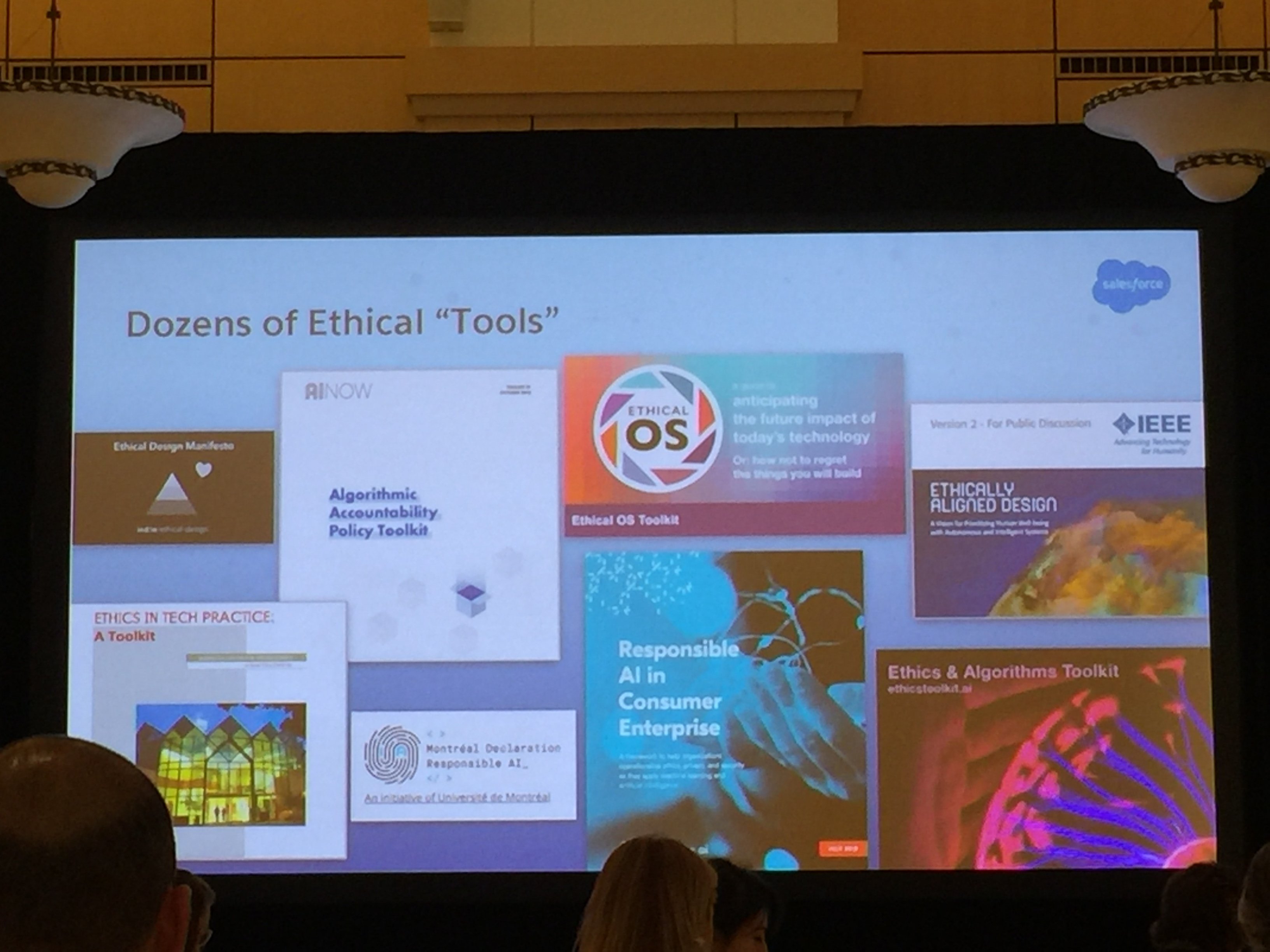

Specifically, Kathy Baxter, an architect of ethical AI at Salesforce, talked about an industry-wide survey she administered on whether companies created AI that respects human rights. On average, 90 percent of people surveyed created ethical tools, but only 57 percent actually used them.

Baxter sought to highlight a correlation between measuring impact and seeing actual change with respect to human rights and vice versa. To create the most progress, she specifically recommended that ethicists in technology companies define metrics of success for human rights and also leverage existing solutions, which include, for example, introducing human rights issues in a Salesforce class about machine learning.

She added that “activating” supporters and sponsors throughout the organization was important, referring to the process of making sure that an organization ensured that people of different ranks, including high-ranking executives, are supporting and speaking out for incorporating human rights with due diligence.

Assessing impacts

Steven Crown, who serves as vice president and deputy general counsel for Human Rights at Microsoft, and Chloe Poynton, a founder of Article One Advisors, gave a presentation about Human Rights Impact Assessments (HRIA), which are used by technology creators to judge how well their AI applications respect humans rights.

Crown stated that HRIA was part of human rights due diligence at technology companies and argued that this work was not only a one-time event, but an iterative process. He called for this work to be a “living document” that companies continually iterate upon. An impact assessment was produced in a collaboration between their organizations to encompass a wide variety of situations. One method they used is known as saliency mapping — an auditing technique to see which inputs were most important to the technological system when determining an outcome.

With this work, Crown and Poynton noted that many questions remained. One of the main ones centered on how one could determine the role an organization played in causing harm. Organizations’ roles can vary from directly causing harm to contributing to harm to being linked with harm. Crown argued that differentiating these causal relationships are critical because each category requires different kinds of remediative action.

In addition, Poynton highlighted the question of how to address harm companies may cause. Harm is caused by denial of opportunities — such as missing a job posting — so individuals may not always even immediately know that they were harmed. Finally, Poynton also acknowledged that HRIAs would not protect technologies from cumulative effects that could disrupt societies negatively, like job loss from high amounts of automation.

One aspect Poynton highlighted in addition to HRIA was that responsible use of AI requires embracing human rights norms. Even technology created to respect human rights can be used in unpredictable ways to cause harm, she said.

“If the world doesn’t care [about respecting human rights], then [effectively upholding human rights is] an uphill battle,” Poynton said.

She spoke of aviation as an example. During peacetime, she said, aviation was used to connect the world and enable travel; in wars, to drop the atomic bomb.

The conference also saw a presentation by Facebook’s director of public policy for Africa, Ebele Okobi, who discussed the company’s approach to protecting human rights. Since Okobi serves as director of public policy for Africa, she focused on talking about her experiences doing so in Africa for Facebook.

Human rights in practice

Jamila Smith-Loud, a user researcher in Google’s Trust and Safety Team, described Google’s efforts to prioritize human rights by integrating social and technical work. In June 2018, Google published its AI principles, delineating seven high-level objectives, and drawing four red lines — one of which included a promise not to use AI in technologies “whose purpose contravenes widely accepted principles of international law and human rights.”

Smith-Loud stated that putting these principles “into practice was the hardest question.” She spoke of the difficulty of trying to manage the complex set of issues surrounding securing human rights. For Smith-Loud’s team, anti-discrimination was a major area of focus, which involved the cooperation of both social scientists and the ones with technical know-how.

Smith-Loud highlighted the role of testing and validation technologies in ensuring their compatibility with human rights. In addition, Smith-Loud emphasized determining failure modes and performing risk assessments on products.

She questioned perceived “tensions” in human rights due diligence. If a technology harms some people, then it does not have a net benefit, she said. Diversity of input through not user testing but also in the decision-making process helps prevent human rights issues, she added.

When concluding, Smith-Loud pushed for a “process-oriented” approach to human rights.

“Human rights due diligence is not a check-box exercise,” she said.

Contact Christina Pan at capan ‘at’ stanford.edu.