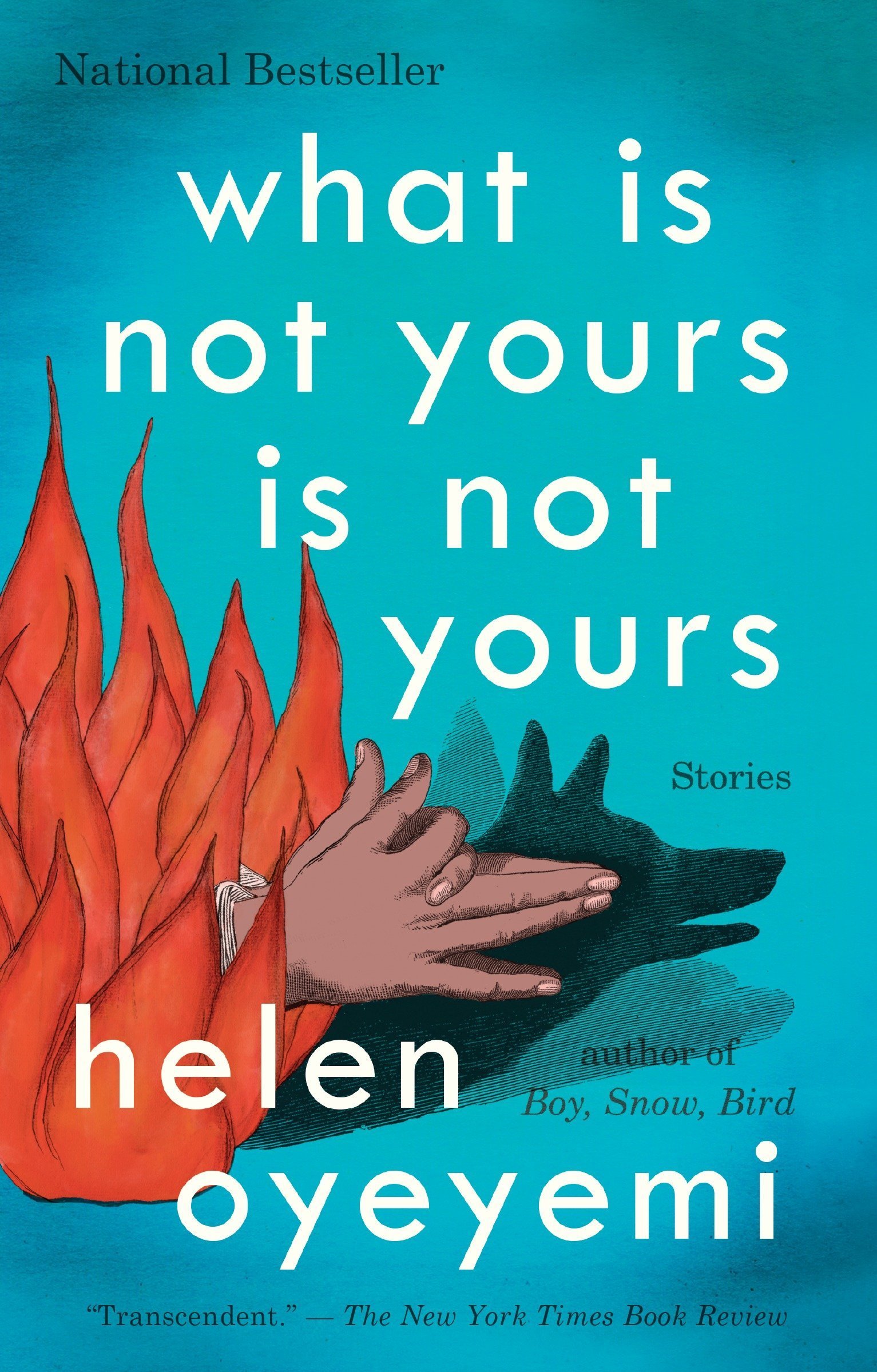

Quoting Emily Dickinson, Helen Oyeyemi’s first short story collection, “What is Not Yours is Not Yours,” begins with the epigraph of “open me carefully” and swiftly delves into an exquisite unravelling of storytelling and reality. To great effect, Oyeyemi explores and broaches the boundaries of traditional narrative expectations, balancing fantasy and the surreal over a precarious slope. All nine of her standalone short stories are tied loosely with the motifs of locks and keys and recurring characters, and each piece dazzles and dazes.

Perhaps most strikingly, Oyeyemi challenges the idea that readers are entitled to certain truths or traditional logical structures of meaning within stories. Some stories draw on magical realism (or fabulism, or its many other names) to casually place surreal elements into the everyday, while others entirely escape this world for a more fairytale-esque retelling. While you may be normally used to reading works with a straightforward plot (even if events are depicted out of order, they can be strung together into a discernible chain of causation), these stories emphasize the absence on the page 一 on what is not yours 一 to open the story to readerly interpretation.

Some stories slyly dance around the question of what is real, with half of “is your blood as red as this?” told from the perspective of a living puppet who was once a female puppeteer. The puppets stubbornly announce their own identities and histories to the narrator, using her as a mouthpiece for the larger world. Likewise, some seemingly standalone pieces, like “drownings,” invent their own mythos, and can be read as fantastical thought-pieces that exist in a different world than the other stories. In a world where a cruel despot drowns those who disagree with him, eventually underwater cities populated by the dead emerge out of the chaos.

And other stories end as they begin, with spiralling beginnings that lead to unexpected results, and often without concrete answers. In the first story “books and roses,” the foundling girl Montse (dramatically left on the steps of a Catalonian monastery as a baby) searches for mother, her only clue a key necklace around her neck. Eventually, she inherits a library and meets her elderly friend Lucy (who may be her potential mother’s former lover), who offers to swap a rose or a book. However, a cloud of mystery still remains, as Montse’s mother never returns in the flesh as she promised, or is ever really confirmed. Even the reunion of Montse and Lucy is bittersweet. They bond through the absence of a notable figure in their lives: however, is it the same one?

Oyeyemi’s beautiful precision of language evokes imagery reflective of thematic elements, contributing to, rather than displacing, the continual surreal experience. As you read, you may marvel over fascinating tidbits, like the “lost woman paintings” in “books and roses,” the diary that contains voices in “if a book is locked there’s probably a good reason for it, don’t you think?,” and the narrator in “presence” who assigns rooms in the house to particular mental functions to compartmentalize her physical and mental space. Every stray detail is a world onto itself. This surreal aesthetic suggests that there are more possibilities beyond the constraints of the page, and giving the reader this openness also ties in with the recurring motif of the lock and key. It is as if the reader is given a universal key and the choice to select their own “fitting” lock out of a haystack of locks.

This dreamlike haziness, however, is often tested in the more realistic stories like “sorry doesn’t sweeten her tea,” which examines the devastating consequences of celebrity idolization. Told through the eyes of two sisters who must reconcile their image of their favorite singer with a man who brutally beats prostitutes, it further examines the lines of reality and fantasy and the potential harm brought onto those who cannot distinguish the difference. However, the meandering beginning, with an admittedly fascinating “House of Locks” with doors that open exactly halfway and a Siamese fighting fish named Boudicca, does not prepare readers for the drastic shift in tone.

Meanwhile, other elements detract from full immersion into the story (though of course, one must consider if this was intentional, considering the mystery that overlays every page). For one, there is a disproportionate attention to several recurring characters, like Tyche the puppeteer from “is your blood as red as this.” Often, these characters are deliberately mentioned in other unrelated short stories and then dismissed, which provides an interesting tension as they appear in both the realistic and more surreal stories. With each appearance, you are prompted to search through the more realistic settings for threads of magic or attempt to rationally explain the magical elements. While their inclusion further blends the lines between stories and worlds, these characters act more like obvious nods to link the collection together, often tangential to the main story at hand.

Nevertheless, with the abundance of enticing details that Oyeyemi rarely dwells upon, some threads will simply be left untied, freed with playful abandon. Arguably, such a swirling chaos of details is more reflective of reality, where day-to-day living involves inevitable sensory overload if you were truly to “take it all in.” Each of these stories feel as if they could continue for several pages longer, but the stories exit as if the reader were only privy to a handful of scenes and nothing more 一 after all, these worlds are not yours. Perhaps in doing so, Oyeyemi reveals the constructions of fiction, startling us from the passivity of consumption.

Oyeyemi demands shifting forms of attention and expectation, placing her short stories with different worlds 一 some recurring, other standalone 一 in conjunction and at-times disjunction, enchanting or eluding our understanding. And rather than offer comforting fictions with predictable forms, she challenges us to accept the unresolvability and unsolvability of reality, jolting us from our reading to embrace the fullness of the now.

Contact Shana Hadi at shanaeh ‘at’ stanford.edu.