To celebrate the close of National Poetry Month, Reads writers gathered to rhapsodize on some of their favorite poems.

Katherine Silk, Staff Writer

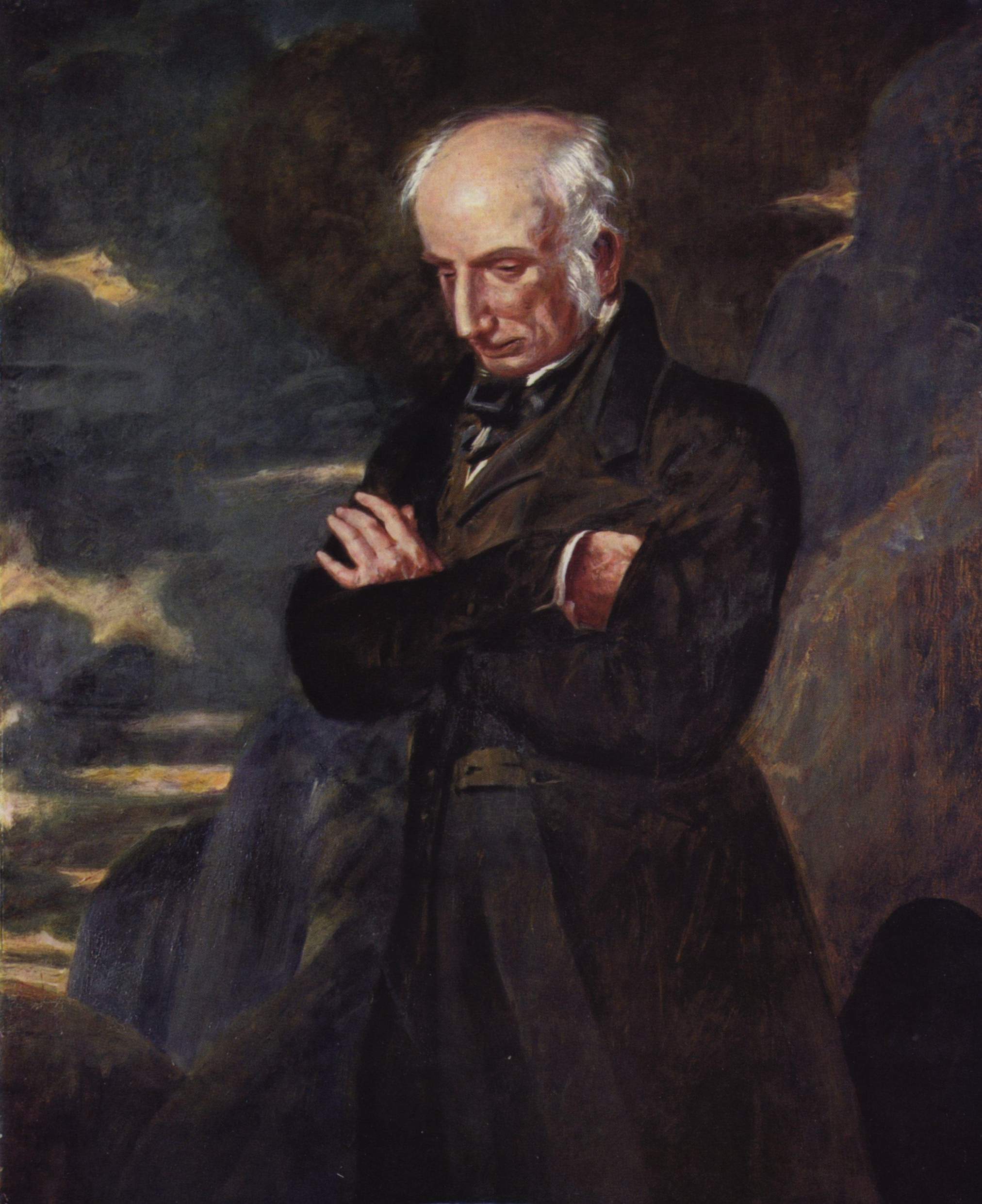

“Daffodils” by William Wordsworth

When I visited Williamsburg, Virginia, over spring break with a friend, one of the highlights for me included exclaiming in delight as I spotted patches of bright yellow daffodils. So enthusiastic was I about the flowers that I even began to quote from one of my favorite poems, “Daffodils” by William Wordsworth.

I have loved this poem for years because of its evocative imagery and calming tone, as well as its rhythmic meter. “Daffodils” is a poem I return to time and again when I simply want to be calmed, relaxed or inspired by a gorgeous scene. In “Daffodils,” Wordsworth paints a masterful image using carefully-chosen words, and I highly recommend the poem to anyone who appreciates spring flowers.

Lily Nilipour, Staff Writer

“The Waste Land and Other Writings” by T.S. Eliot

Before last week, in my whole life I had not read a single line of T. S. Eliot’s poetry, English major that I am. Or so I thought.

Upon opening to the first poem in the book – “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” – something felt strange. The first three lines felt oddly familiar. I wracked my brain; surely, surely this could not be so. I realized then the source of my déjà vu: Bo Burnham, in his song “Repeat Stuff,” quotes these exact lines as a nostalgic remembrance of what love songs used to be.

“The Waste Land” and the rest of Eliot’s work is notoriously famous for its intentional difficulty to comprehend. Often, following the allusions in his poems leads not to clarification or understanding but to further confusion. He drops in full, untranslated lines from other texts – he doesn’t even give us footnotes of translations, either.

So, I find it intriguing and a bit ironic to discover that my first entry into T. S. Eliot was a widely popular comedy routine. Regardless of how inaccessible he makes himself, Eliot somehow still resonates with lots of people. The images and evocations of the poetry in this collection are melancholy and beautiful, even if sometimes overly-intelligible to the point of unintelligibility.

Mark York, Staff Writer

“The Orange Bottle” by Joshua Mehigan

When it comes to the written word, poetry has been a constant source of confuzzlement for me.

And while I could make an attempt to understand the unknown, I would much rather rest contently in my own ignorance by making you confused as well. This is my opportunity to highlight the wild side of this oft prim and proper field, and the wildest poem I ever came across is “The Orange Bottle” by Joshua Mehigan.

This poem, this 20-page epic, depicts a man going off his medication, and as the story goes on the subject begins to experience increasingly nightmarish distortion. “The Orange Bottle” can be accurately described as a fever dream nursery-rhyme as the poetic structure itself begins to warp. We go from clean, rhythmic stanzas to off-rhymes, added lines, sporadic spacing, sudden tangents – the poem bends with the subject’s mental state, manipulating the piece in strange ways thematically, audibly and visually. Mehigan creates a dark wonderland, and the reader truly feels submerged in this world – we want out, yet we can’t stop reading.

So, if that sounds like your thing, I would certainly recommend it. If nothing else, this is a means of truly pushing what the poetic medium can do, and I for one am quite morbidly curious about seeing how Mehigan twists the page.

Shana Hadi, Desk Editor

“Citizen: An American Lyric” by Claudia Rankine

In this supremely moving collection published in 2014, Rankine melds poetry with social criticism, examining the double consciousness of the African-American experience. Separated into seven chapters intermixed with visual art and images, each chapter dwells on a distinct theme, ranging from micro-aggressions that Rankine or her friends have experienced personally, to a meditation on the outrage-inducing, “over-officiating” referees and media attention towards tennis champion Serena Williams. Likewise, the artworks that punctuate the book offer additional weight to the themes, like Glenn Ligon’s “Untitled (I Do Not Always Feel Colored)” which references Zora Neale Hurston and examines skin color as a social construction.

Perhaps the most reflection-inducing chapters are those where she places the reader into a black persona who is “invisible” and prone to “erasure.” With the series of real-life micro-aggressions told through the second person, each poem wears down on you, chipping away at your sense of personhood as if with a dull blade. Rather than using flagrant forms of discrimination, Rankine demonstrates how even indirect forms of prejudice continue to wound.

One poem that I cannot forget considers the American conflict between the “historical self” and the “self self.” A black narrator sits across from her white friend and then suddenly, with a turn in conversation, their “attachment seems fragile” amidst the weight of their American positioning, beyond the safety of their personal histories. In such an event, how does one smooth over the interaction and contend with the constant mental disharmony?

Later in the collection, with a line that leaves ash in your mouth, Rankine wearily concludes, “This is how you are a citizen. Come on. Let it go… Move on.”

But this answer is meant to be unsatisfying.

Contact Reads beat desk editor Shana Hadi at shanaeh ‘at’ stanford.edu.