Stanford researchers released findings last Monday that could revolutionize the pursuit of new chickenpox treatment strategies. But a long legacy of virus research doesn’t make the campus immune to vaccine-preventable diseases.

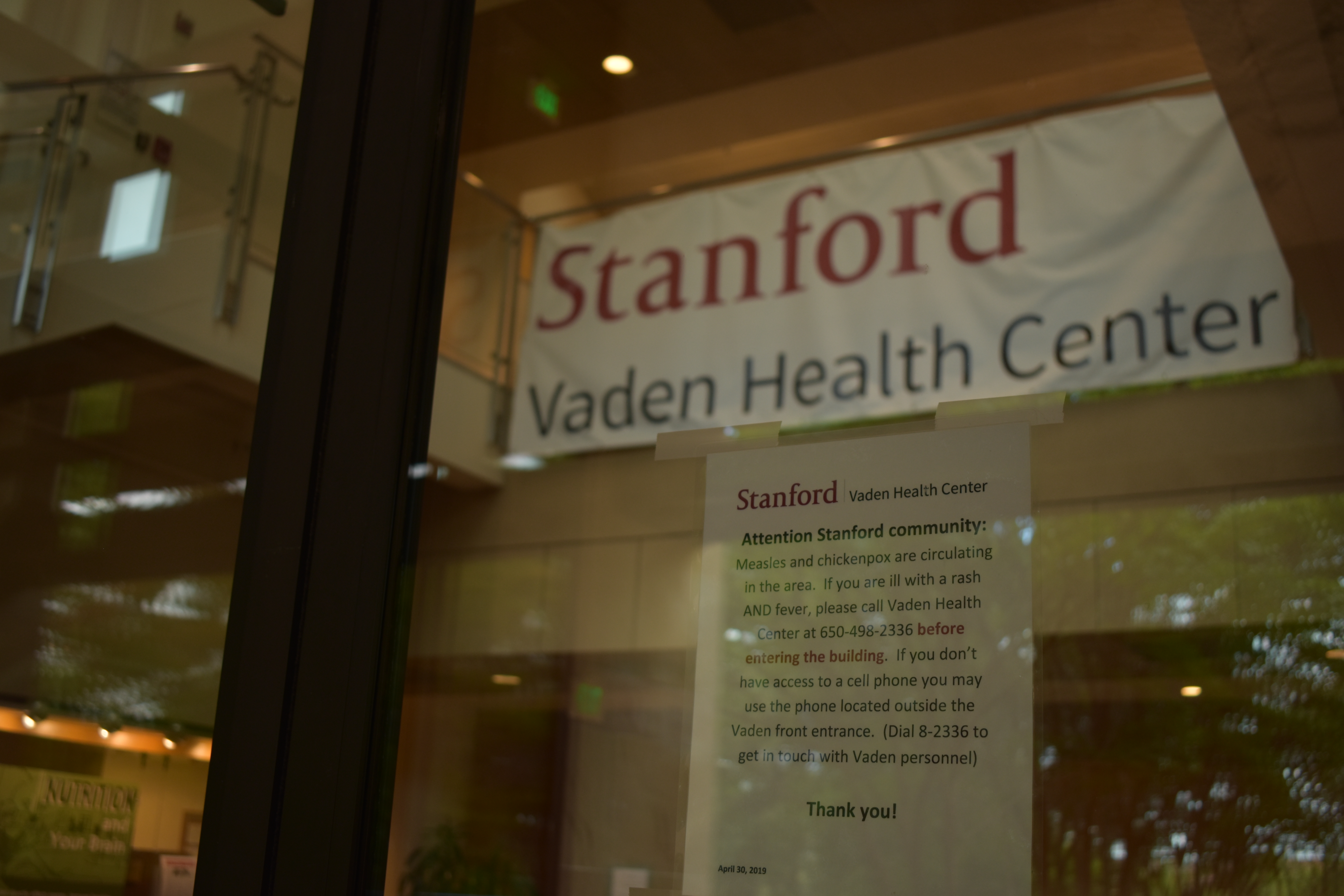

In the past two months, the Stanford community has had one chickenpox infection and one potential measles exposure with no known resulting infections, Communications Director for Student Affairs and Vaden Health Center spokesperson Pat Harris wrote in a statement to The Daily. While the vaccines for chickenpox, also known as varicella, and measles are highly effective, a high percentage of people must receive the vaccines in order for the group as a whole to be protected in case of an outbreak.

Researchers at the new Stanford-SLAC National Accelerator Cryo-Electron Microscopy facility are applying new technology to create detailed renderings of biological structures. They are now able to take images of the varicella-zoster virus — responsible for chickenpox in children and shingles in adults — that are accurate to the atomic level, showing in detail the shape of the proteins on the virus surface. Tracking these changing shapes as the virus infects a cell could reveal the underlying mechanics of virus infection and inspire new methods to prevent infections.

The history of varicella-zoster virus research at Stanford extends far beyond that. Ann M. Arvin, professor of pediatrics, microbiology and immunology at the Stanford School of Medicine, conducted research on the virus beginning in the 1970s that led to the development of the chickenpox vaccine. Arvin has since shown that an inactive form of the chickenpox vaccine can be effective in preventing shingles among adults with compromised immune systems following a stem cell transplant. In 2017, Stanford immunology and rheumatology professor Cornelia Weyand and colleagues published research on explaining higher risk of shingles among people with coronary artery disease.

Less than four weeks before last Monday’s varicella-zoster virus research announcement, Vaden Health Center diagnosed a student with chickenpox, according to Harris. This, in turn, was a few short weeks after Santa Clara County listed Hoover Tower as a potential site of measles exposure following a visit from an infected international traveler. No students are known to have been infected with measles this year, according to Harris, and there were no known consequences of the potential exposure at Hoover Tower.

While vaccine development led to widespread immunity to chickenpox and measles in the U.S., recent outbreaks have captured headlines this year across the U.S. and in California. In April, over 700 students and staff members were quarantined due to measles outbreaks at University of California, Los Angeles and California State University, Los Angeles. In March, a student at California Polytechnic State University developed chickenpox.

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that this year has seen the “greatest number of cases reported in the U.S. since 1994 and since measles was declared eliminated in 2000.”

While Harris stated that Vaden could not comment on individual cases, she wrote to The Daily that under-vaccination is responsible for the “epidemic numbers” of measles cases seen across the country. She added that an unvaccinated person exposed to measles has a 90 percent probability of contracting the disease.

In order for a population as a whole to have “herd immunity” from the spread of a single case of a vaccine-preventable disease, a certain threshold must be vaccinated. This threshold depends on how infectious the disease is; for measles, the threshold is around 93 to 95 percent.

While the threshold for chickenpox depends somewhat on research assumptions, Rich Wittman, medical director of the Occupational Health Center at the Environmental Health and Safety Department (EH&S), said in an interview with The Daily that the good news is that over 95 percent of Americans are immune to chickenpox, including presumably those over age 40 and even a high majority of those who have no memory of infection.

“So I think a lot of that data is comforting, were there to be a chickenpox case on campus,” he said.

All Stanford students are required to show evidence of having received two doses of the measles, mumps and rubella (“MMR”) vaccine, in accordance with CDC guidelines. The vaccine is extremely effective, Wittman said: One dose of MMR is 93 percent effective in preventing measles, and two doses are at least 97 percent effective. Some Stanford students have additional vaccine requirements, such as medical students, who must also receive two doses of the chickenpox vaccine.

Vaden recommends that “all students review their vaccination and illness history with their healthcare providers to consider whether additional vaccinations are appropriate to help reduce the risk of vaccine-preventable diseases,” Harris said. She added that students can review their immunization records through Vaden’s online tool.

California is one of three states to prohibit both religious and philosophical vaccine exemptions for children entering in daycare, preschool and K-12 schools. Stanford students are able to submit a religious or philosophical exemption “in order to adhere to legitimate religious practices and beliefs or philosophical positions” that emerge from obligations to “a wider religious community” or shared “coherent, justifiable philosophical principles,” according to Vaden’s exemption form instructions.

The exemption form instructions clarify that “personal attitudes, beliefs or preferences are not grounds for an exemption” and ask students to comment on how they address “social obligations to [their] broader community” and to explain the “tension between [their] desire not to be immunized and [their] social obligation to participate in creating ‘herd immunity.’”

For Stanford faculty and staff, MMR and chickenpox immunization requirements are job dependent.

“It’s not a de facto requirement to be employed,” Wittman said. Instead, “There are … many groups that set policies regarding immunization and prevention,” and requirements depend on factors such as patient contact, potential exposure to agents in a lab setting, work with preschoolers and children and international travel. In the case of patient contact, requirements are set by Santa Clara County, Cal/OSHA and Stanford Hospital depending on the particular vaccination.

The EH&S department, the principal health and safety office at Stanford University, collaborates with a number of campus partners to follow the guidance of the CDC, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the State of California Division of Occupational Safety and Health (Cal/OSHA), as well as Stanford-specific guidelines, with the “goal of supporting a safe and healthy campus environment.”

Adults who have not received the MMR or chickenpox vaccine are still able to be vaccinated. CDC guidelines for MMR recommend that higher-education students who have not received vaccination or do not have other evidence of immunity, such as a blood test or birth before 1957, receive two doses of the MMR vaccine, at least 28 days apart (barring immune-related exceptions). The CDC recommends at least one dose for other adults without evidence of immunity.

People older than 13 who have not received varicella vaccination or other evidence of immunity are recommended by CDC to receive two doses of the chickenpox vaccine, and adults 50 and older are recommended to receive a shingles vaccine.

Contact Elise Miller at elisejl ‘at’ stanford.edu.